In a very complicated decision (Department of Commerce v. New York) whose consequences are not at all clear, a 5–4 majority of the Supreme Court put the Trump administration’s plans to ask a citizenship question on the 2020 Census forms on hold until such time as Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross comes up with a better rationale for his actions than a voting-rights enforcement claim that nobody believes. Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion, which splintered the Court into an array of concurrences and dissents (with conservatives agreeing with his ruling that no constitutional violations were committed by the administration), but the four SCOTUS liberals joined with him in the ultimate decision to stop the use of the question at least temporarily.

After discarding a long series of objections to the citizenship question, Roberts eventually agreed with a lower court’s determination that Ross’s stated rationale that the administration needed this data to improve Voting Rights Act enforcement (which he testified to under oath before Congress, by the way) was a sham, as one might suspect given Team Trump’s hostility to voting rights. This made the question a possible violation of the Administrative Procedures Act:

[V]iewing the evidence as a whole, we share the District Court’s conviction that the decision to reinstate a citizenship question cannot be adequately explained in terms of DOJ’s request for improved citizenship data to better enforce the VRA. Several points, considered together, reveal a significant mismatch between the decision the Secretary made and the rationale he provided …

We are presented, in other words, with an explanation for agency action that is incongruent with what the record reveals about the agency’s priorities and decision-making process. It is rare to review a record as extensive as the one before us when evaluating informal agency action — and it should be. But having done so for the sufficient reasons we have explained, we cannot ignore the disconnect between the decision made and the explanation given …

The reasoned explanation requirement of administrative law, after all, is meant to ensure that agencies offer genuine justifications for important decisions, reasons that can be scrutinized by courts and the interested public. Accepting contrived reasons would defeat the purpose of the enterprise. If judicial review is to be more than an empty ritual, it must demand something better than the explanation offered for the action taken in this case.

Thus Roberts agrees on the narrowest possible grounds with the lower court’s decision to “remand” the case to the Commerce Department to see if they can come up with a better explanation for the citizenship question than the lies Ross told to Congress.

Roberts does not mention the very recent evidence from the files of the late gerrymandering wizard Thomas Hofeller, which revealed that the voting-rights rationale was generated purely as a smoke screen for invidious racial and partisan motives, though clearly something has happened to discomfit the Chief Justice since the April oral arguments, after which a decision to let the administration have its way was universally predicted. But presumably the New York district court supervising Ross’s response is free to look at that as well.

I say “presumably,” because the path forward in this case is exceptionally murky. All along, the Trump administration has stipulated a July 1 deadline for mailing out Census forms with or without the citizenship question; that indeed was the basis for the expedited SCOTUS review of the case, which had not gone through any Court of Appeals. But groups challenging the question have found internal Census documents indicating the mailing could be done as late as October, albeit at additional cost. We are probably going to find out very soon when the real deadline actually falls.

And now, from tweets in the middle of the night direct from Osaka, Japan, comes this influential opinion:

It’s quite possible that Ross and his lawyers can come up with a fresh excuse for the citizenship question that would be less incredible than the administration’s devotion to voting-rights enforcement and, under the Supreme Court’s very limited requirements, get it all done in time to include the question on the Census. The likelihood that today’s decision was a Pyrrhic victory for opponents of the inclusion was pointedly raised by law professor John Blackman, alluding to the famous Roberts opinion on Obamacare:

Largely incontrovertible is that the question’s ultimate fate could be quite consequential, as I explained earlier this year:

The administration’s own estimates show that as many as 6.5 million people — many of them recent immigrants fearful of arrest and/or deportation if they become visible — won’t answer the Census at all if there is a citizenship question. Since federal funding formulas typically depend on Census figures, states with serious undercounts will get screwed to the tune of many billions of dollars. Congressional and state legislative reapportionment and redistricting are also based on Census figures; California could lose congressional seats and electoral votes, and areas with sizable immigrant populations within a variety of states could lose clout in Congress and in state legislatures.

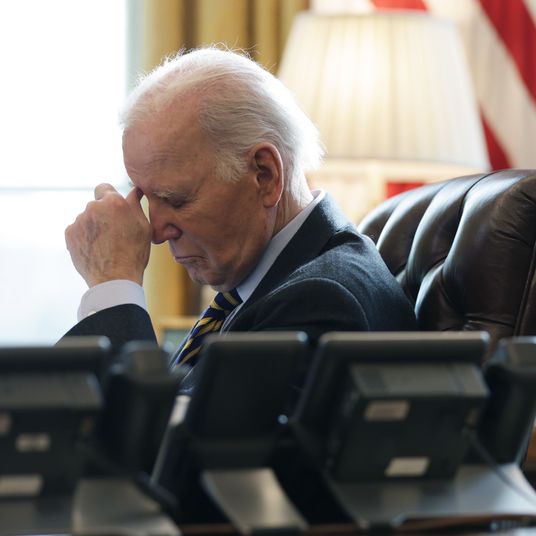

It’s a BFD, as Joe Biden might say. But while the Trump administration definitely suffered a setback today in its efforts to use the Census to reinforce its tough-on-immigrants agenda, it’s too early to tell if Ross will get his way. There ought to be consequences for his past lies, but in this administration, lying is standard operating procedure.