While Donald Trump was imploring nonwhite Democrats to “go back” to the “crime infested places from which they came” this week, a group of his sympathizers gathered in D.C. to lament America’s bitter social divisions, and call for a return to national unity.

The mission of the Edmund Burke Foundation’s inaugural National Conservatism Conference was to develop a new, post-Trump conception of the American right’s political project, one less allergic to state intervention in the economy — and more vigorous in its promotion of communitarian social values — than the “market fundamentalism” that reigned supreme in Paul Ryan’s Republican Party.

To some liberals, this rebrand looks like an attempt to put lipstick (or maybe a tweed jacket) on a pig: Conservative intellectuals are just trying to reframe their movement’s embrace of virulent xenophobia as something more rational and respectable than it actually is. But national conservatives insist that the impetus for their creed is only peripherally related to Donald Trump; their true concern is the collapse of social cohesion in the United States. Yoram Hazony, the Israeli right-wing intellectual who co-convened the conference, contends that “national cohesion is the most important thing to be thinking about right now … You can’t have cohesion over nothing. You have to have cohesion over something shared.” And that something is national identity.

For conservatives in search of an official, overriding political goal, the appeal of “social cohesion” isn’t hard to intuit. America’s contemporary economy and culture really are atomizing. No small number voters — left and right — find the hyperindividualism of modern life alienating and unfulfilling. The people living in deindustrialized towns that comprise an increasingly large share of red America have good cause to mourn the decline of communitarian institutions. And for many Christian conservatives, the quest for moral hegemony is inextricable from a longing for a society unified by common purpose.

Plus, “social cohesion” serves as a high-minded rationale for restricting immigration. Social trust and solidarity is often lower in ethnically diverse nations with large foreign-born populations than it is in more homogeneous countries. By emphasizing this fact, conservatives can insist that Donald Trump’s immigration agenda (or a kinder, gentler version thereof) is not a leading cause of political polarization but a necessary remedy for it.

But if it’s clear why conservative nationalists would say that their goal is social cohesion (and why many of them might earnestly believe that), it’s equally clear that they’ve set themselves an impossible objective.

Put simply, national conservatism’s day has come too late. Their movement’s leading thinkers and social base do not want social cohesion for its own sake — they want it on white traditionalist America’s own terms. Tucker Carlson and his audience aren’t interested in reviving the civic nationalism of Barack Obama, but rather, in restoring social conservatism’s long forfeited cultural supremacy. And in the 21st-century United States, that latter mission is incompatible with promoting national unity.

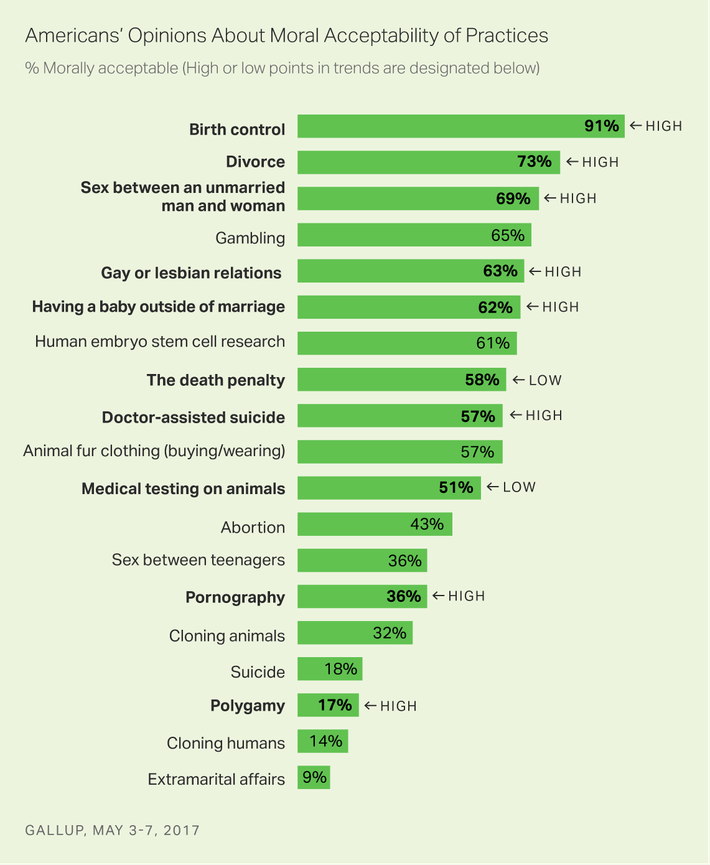

In the postwar period, when upward of 80 percent of Americans were both white and Christian, national conservatism’s project would have had some plausibility. But today, white Christians account for 43 percent of the population, a share that is set to steadily decline as America’s aberrantly nonwhite and secular rising generations displace its older ones. Meanwhile, the American electorate is now more socially liberal than it’s ever been. In this context, legally enshrining the Christian right’s conception of personhood — or culturally entrenching Donald Trump’s conception of patriotism — and fostering social cohesion are irreconcilable objectives.

This simple truth, and national conservatives’ will to elide it, were both reflected in the conference’s keynote speech by Missouri senator Josh Hawley. Hawley has established himself as national conservatism’s most vigorous proponent on Capitol Hill. Unlike other Republicans who have gestured toward the new consensus, Hawley has put economically heterodox legislation where his mouth is. But for all his avowed concern with America’s descent into “faction” (and broadly resonant critiques of concentrated capital), Hawley has no interest in unifying our actually existing nation, only the traditionalist one that lives in red America’s nostalgic imagination.

Nevertheless, the senator opened his speech to the conference by claiming otherwise:

The great divide of our time is not between Trump supporters and Trump opponents, or between suburban voters and rural ones, or between Red America and Blue America. No, the great divide of our time is between the political agenda of the leadership elite and the great and broad middle of our society. And to answer the discontent of our time, we must end that divide. We must forge a new consensus.

The idea that there is no great divide between red and blue America rings false when voiced by Third Way Democrats. Coming from a politician like Hawley — who wants to outlaw all forms of abortion, defund sanctuary cities, and combat Nike’s attack on American values — it’s patently absurd. The “leadership elite” aren’t the only ones who oppose Hawley’s vision for the country, and “the broad middle of our society” isn’t unified behind it.

To camouflage this reality, Hawley uses variations on the phrase “the American middle” to conflate our nation’s broad middle-class with the conservative-leaning, geographic middle of the country. He then implies that social liberalism is an esoteric ethos unique to those at the very top of America’s socioeconomic hierarchy. Together, these two moves allow him to recast the red-blue culture war as a populist conflict between the many and the few:

For years the politics of both Left and Right have been informed by a political consensus that reflects the interests not of the American middle, but of a powerful upper class and their cosmopolitan priorities.

This class lives in the United States, but they identify as “citizens of the world.” They run businesses or oversee universities here, but their primary loyalty is to the global community. And they subscribe to a set of values held by similar elites in other places: things like the importance of global integration and the danger of national loyalties; the priority of social change over tradition, career over community, and achievement and merit and progress.

… The cosmopolitan elite look down on the common affections that once bound this nation together: things like place and national feeling and religious faith.

They regard our inherited traditions as oppressive and our shared institutions — like family and neighborhood and church — as backwards …

What they offer instead is a progressive agenda of social liberation in tune with the priorities of their wealthy and well-educated counterparts around the world.

And all of this — the economic globalizing, the social liberationism — has worked quite well. For some. For the cosmopolitan class.

Whom it has not served are the people whose labor sustains this nation. Whom it has not helped are the citizens whose sacrifices protect our republic. Whom it has not benefited is the great American middle.

Here, Hawley suggests that the only Americans who prioritize social change over tradition — or their careers over tending to the communities they were born into — are cosmopolitan elites who “run businesses or oversee universities”; in reality, this describes the lion’s share of Americans who work in urban-based businesses, or graduate from universities. He then suggests that no American “whose labor sustains this nation” or “whose sacrifices protect our republic” has been well-served by “social libertationism.” Which makes sense if one pretends that only Davos attendees disagree with conservatives on abortion and LGBT rights. If one acknowledges that there are some feminists in the United States who work for a living, or that there are LGBTQ individuals who serve in the armed forces, Hawley’s assertion becomes absurd. When the senator says that the cosmopolitan elite “regard our inherited traditions as oppressive,” it is plain that the “we” he speaks for is only “the great American middle” if that term is a synonym for conservative Christians.

The great divide in Hawley’s speech is the conventional partisan one; his only substantive innovation is to wed some form of anti-monopoly, industrial policy to the GOP’s preexisting worldview (for a more detailed look national conservatives’ nascent economic agenda, see this piece by Park MacDougald). He pretends that this is not the case because acknowledging the true identities of his speech’s “we” and “they” would render his vision for rebuilding “common purpose” and social solidarity ridiculous. In the 21st-century United States, restoring social cohesion on Josh Hawley’s terms would require authoritarian rule. Nothing else would make America’s growing population of socially liberal urbanites as politically and culturally marginal as Hawley’s keynote imagines them to be. To revive social cohesion (or at least, something approaching social harmony) in a democratic, 21st-century U.S. — a nation that is multiracial, religiously diverse, and culturally divided — would require popularizing an ethos of cross-cultural solidarity and toleration for difference.

If some group of civic-minded patriots formed a political movement to achieve this end, they might call themselves “liberal cosmopolitans.”