Speaking on Glenn Beck’s podcast last week, former South Carolina governor-turned-United Nations ambassador Nikki Haley described the difficult process she underwent in 2015, when she presided over the Confederate battle flag’s removal from the statehouse grounds after Dylann Roof murdered nine black people inside a Charleston church; his manifesto had included photos of him brandishing it.

Haley’s explanation for her decision:

And here is this guy that comes out with this manifesto, holding the Confederate flag, and had just hijacked everything that people thought of. We don’t have hateful people in South Carolina. There’s always the small minority that’s always gonna be there, but, you know, people saw it as service, and sacrifice, and heritage, but once he did that there was no way to overcome it, and the national media came in in droves.

The “Confederate flag” (usually a Virginia battle flag or Navy Jack never used as a national flag by the Confederacy) is indeed about “service” — albeit that performed under duress by the black people whose enslavement its followers sought to preserve. The prospect of “sacrificing” the legal right to own them as property was of paramount concern to its white proponents. And the “heritage” it bequeathed was one of civil war and terrorism in the name of white supremacy — campaigns its champions have since recast, absurdly, as sources of pride.

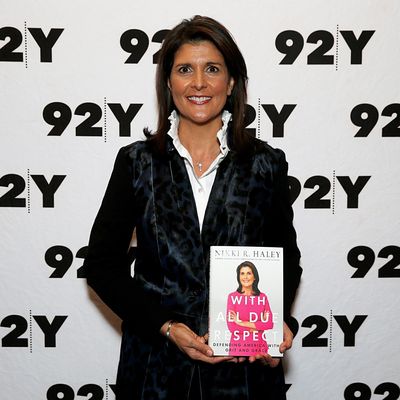

Haley struck back at the pundits and “outrage media” who used her own words to characterize her as a Confederate apologist by firing off two tweets lambasting them for their bad-faith attacks. She added that if people were really interested in her views on the flag, they should consult chapters one and two of her new book, With All Due Respect: Defending America With Grit and Grace. So I did.

My time would’ve been better spent elsewhere. Both chapters reveal that Haley’s views on the flag are precisely how she characterized them in her interview with Beck, and again on Wednesday in an op-ed for the Washington Post: It is, to her, a symbol whose meaning is a point of understandable disagreement between “good-hearted” and “well-intentioned” South Carolinians of varying backgrounds — those who see it as a “symbol of heritage and ancestry,” and others who see it as “a symbol of hate and oppression.”

(Conspicuously left unmentioned is that the former are almost exclusively white, and the heritage they’re celebrating hinges on a war waged to preserve chattel bondage and unencumbered white supremacism — a condition far from abstract to many in the latter camp, whose enslaved black ancestors and their terrorized descendants bore and bear daily witness to the cruelty wrought by the Confederate legacy.)

But perhaps more interesting — by which I mean only very slightly more interesting — is how Haley seems to have arrived at this conclusion. The biographical information she shares in those first two chapters is an effort to cast herself as an honest broker between black and white South Carolinians, whose mutual tensions often placed her in a position where she was asked to choose sides. She illustrates this dynamic by recounting a third-grade kickball game between black kids and white kids. Haley, who is Indian-American, was asked to decide which one she was. “I’m neither! I’m brown!” she yelled, then grabbed the ball and ran off to start the game before anyone could object.

An instinct for conciliation honed by such formative experiences with racism followed her into government, she explains, where she saw herself as a unifier. (That she chose to pursue this endeavor as a standard bearer for what is functionally the party of white people fails to earn explicit mention.) And it was her impulse to smooth over differences and focus on keeping South Carolinians unified in their grief after the Charleston massacre and, before that, frustration with the police shooting of Walter Scott in North Charleston, that’s led her to criticize advocates and political leaders who’ve dared to suggest — either in public or privately to her — that both incidents held unique resonance for black people rather than all South Carolinians equally, and that South Carolina’s specific history with racism had somehow informed them.

Thus Haley positions herself, in her recollections, as fighting on behalf of everyday residents of the state against outside agitators who would sow discord, diminish the racial progress that South Carolina has made over the years, and create an environment of antagonism where it, apparently, would’ve otherwise struggled to find purchase. These supposed agitators included none other than President Obama, who the day after the shooting analogized the Charleston murders to the KKK church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, where four black girls were killed in 1963:

[Toward] the end of his remarks, President Obama made a historical analogy that I thought was wrong. He mentioned the four little African American girls who were killed [in 1963] … [He] quoted Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who said of the 1963 victims, “We must be concerned not merely about who murdered them, but about the system, the way of life, the philosophy which produced the murders.

Haley attempts to refute this by explaining that “a lot has changed in the South since 1963” and suggests that Obama was “[implying] the South was somehow to blame” for the Charleston tragedy. The president’s behavior only got more unforgivable from there, in her retelling. She describes in unflattering terms Obama’s phone call to her from Air Force One:

From the moment he got on the phone, the president was very short and to the point. There was a coldness to his voice. The president said he was calling about the shooting, but didn’t offer his condolences. When I told him I was worried about South Carolinians being able to get through the tragedy without violence, he didn’t offer any help or words of encouragement. He seemed to feel the way he had hinted at before — that South Carolinians were partly to blame for the murders.

“It seemed to me,” Haley concluded, “that South Carolina would have to go at it alone.” I can’t speak to Obama’s emotional state at the time, but Haley’s “us versus him” framing strikes me as laughable given the likelihood that black South Carolinians’ affinity for their black president — whom they backed by staggering margins both times he ran for election — far outstripped that for their Republican governor, whose party compatriots regularly defended and rationalized the same Confederate flag flown by Dylann Roof and whom the black electorate as a bloc invariably votes against. Perhaps they, not Haley, were the people foremost on Obama’s mind at that moment. Perhaps the suggestion that some South Carolinians bore responsibility for the Charleston massacre was not totally outrageous given that the killer was a South Carolinian who cited as his inspiration South Carolina’s own sordid history.

But Haley’s self-casting as the state’s defender against outsiders who would impugn the character of its residents by suggesting the problem in Charleston was bigger than a single deranged individual is most illuminating in her passage about Jesse Jackson, the civil rights leader and two-time Democratic presidential candidate:

I had breakfast with him almost every other day in the weeks following the murders. Initially, I was trying to keep him close so he wouldn’t add anything to the media circus surrounding the murders …

I consider Jesse Jackson a friend to this day because he took time to know me as a person. He didn’t come into South Carolina and take shots at me just because I was a Republican. He didn’t come into my state to stir up trouble. He came in to understand.

That Jackson didn’t need Haley’s help or insight to better “understand” much of anything about racism in South Carolina is a near certainty. He is himself a South Carolinian. Born in Greenville in 1941, he grew up under Jim Crow laws that dictated he attend segregated schools, drink from segregated water fountains, sit at the back of public buses, and otherwise live his life in mortal fear that transgressing any of these precepts would result in his arrest, assault, dismemberment, or death. Yet to Haley, he was another outsider who nevertheless thankfully defied her expectations that he’d “stir up trouble” in “[her] state.” Implied in her characterization is a notion of belonging that marginalizes homegrown South Carolinians like Jackson while maintaining room for white people who glorify secession, and suggests a shared assent among black and white current residents regarding the Charleston massacre — and its broader implications — that is almost certainly more complex than her rosy view of statewide unity suggests.

I can only imagine the treasure trove of screeds criticizing black leaders for being divisive and unfair to racists or anecdotes describing neo-Confederates as good-hearted innocents awaited me had I finished Haley’s book. Sadly, I followed her instructions to the letter and only read chapters one and two. She remains indisputably the governor who oversaw the toppling of the Confederate flag from above the South Carolina statehouse, but still maintains — in the book as she did in her interview with Beck — that her hand was forced by a racist who’d hijacked its otherwise noble meaning. (“I worried that allowing the killer to define what the flag represented for everyone was a surrender,” she writes. “Why should he, of all people, be given that power?”)

But concede she did, and South Carolina — she admits — is better for it. If only I could say the same of myself having read the early chapters of her book. As no doubt plenty of my colleagues and readers could’ve told me from the beginning, the primary accomplishment of my having endured Nikki Haley’s book is that Nikki Haley got another person to endure her book. But I did it so you don’t have to. Don’t be like me. There are other books. Read those instead.