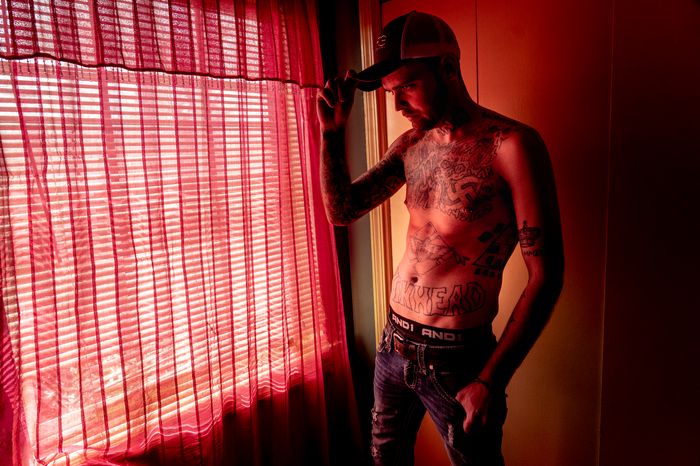

A little over a year ago, Austin, 31, decided he wanted out of the Aryan Brotherhood, a gang of white supremacists he’d joined early in his 10-year prison sentence for aggravated robbery. By the time Austin was paroled, the Brotherhood was more important to him than his real family. “Me and my wife could have been out eating, or I could have been at Chuck E. Cheese with my son,” he says, when interviewed as part of New York’s photo-documentary portfolio on white supremacy, “and [the Aryan Brotherhood] would call me because they needed me to run drugs or they needed me to go beat someone up or rob someone. I would just leave them there.”

When Austin went back to prison on a parole violation, he started looking for a way out of the Brotherhood. Founded by white bikers to protect white inmates inside prisons, the Aryan Brotherhood is not bound by racist ideology alone; it is also a criminal syndicate known for manufacturing and running drugs, armed robbery, and murder for hire. The gang’s motto, “Blood in, blood out,” is a deadly oath. When Austin told the Brotherhood he was dropping out, he was told he knew too much. Austin says his “brothers” beat him with metal locks wrapped in socks and stabbed him with ice picks. He was hospitalized and transferred to another prison, where he was attacked again. “I still get messages on Facebook that they can’t wait to see me, sleep with one eye open. It’s just an ongoing thing,” he says. For “formers” like Austin, removing tattoos is a matter of life and death — as long as he wears the tattoos, members of the Brotherhood will target him.

When Austin got out of jail he met TM Garret, a former white supremacist who now helps people who are looking to get out of white-supremacist groups. Garret was a skinhead in his native Germany until 2004. He moved to the United States in 2012, a jarring experience that helped him realize two things: First, leaving a hate group was not enough. “Getting out of a hate group is one thing, and changing is another thing. I was still a racist,” Garret says. Second, the United States was not the “melting pot” of coexistence he’d been promised. “I moved to Memphis, Tennessee, and realized that doesn’t exist.”

Garret started working with other formers in 2017, and his Erasing the Hate campaign helps them remove their tattoos, which can be a long, expensive process. Some tattoo artists refuse to work on clients with neo-Nazi tattoos, while others have relationships with the Aryan Brotherhood themselves, making removal a fraught, dangerous process for people living in small rural communities. “Are artists judging me because I have the tattoo, or are they judging me because I want it removed?,” asks Garret. He found a tattoo artist willing to work on formers without judgment and has since helped them remove some 150 tattoos free of charge.

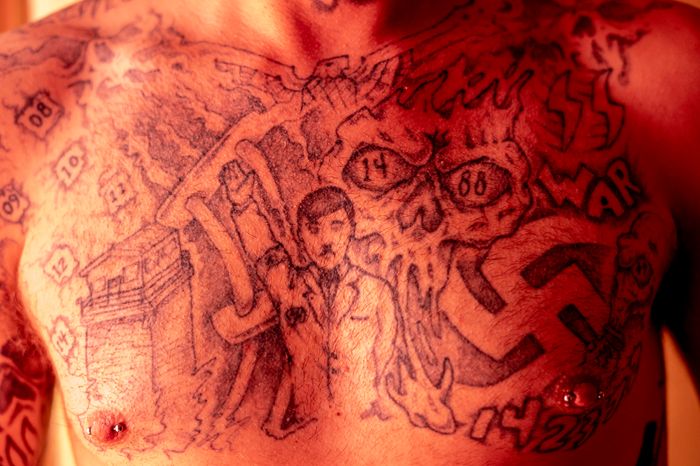

Austin has been gradually removing the swastikas, the SS bolts, a portrait of Hitler, and the word skinhead drawn across his abdomen. “I have more than 50 hours left just on my chest piece,” he says. “Once I get all these tattoos removed, it’ll die out. They’ll slowly just leave me alone.”