As the number of cases of Wuhan coronavirus continue to spike, and fears of a pandemic rise, scientists and public-health officials are scrambling to understand the scope and threat of the new outbreak. The virus, 2019-nCoV, has already infected more than 4,500 people in 14 countries and killed more than 100 in China — and those numbers will undoubtedly rise in the coming days. In response, China has instituted unprecedented draconian measures in an attempt to contain the outbreak, but it’s possible the quarantine will not be effective, and the coronavirus will continue to spread.

Unfortunately, scientists still have more questions than answers about the new coronavirus. Below is a look at what they do and don’t know so far.

How big is the outbreak, really?

For now, the full extent of the outbreak, lethality of the new coronavirus, and risk of it spreading remain unclear — but the available evidence and estimates continue to alarm public-health experts.

Officially, at least 4,515 people around the world have been infected with 2019-nCoV as of Tuesday. Most of those cases are from the epicenter of the outbreak — the city of Wuhan in China’s central Hubei province. There have also been scattered cases confirmed in more than a dozen other countries involving people who had recently traveled to Wuhan, including cases where human-to-human transmission appears to have occurred.

But the actual number of infections is probably much higher, according to researchers studying the epidemic.

Some experts estimate that at least tens of thousands of additional people are likely to have been infected in China than officially reported, and China’s health minister has said that the new coronavirus appears to have become easier to transmit, including among people who show no signs of infection.

Infectious disease experts at the University of Hong Kong said on Monday that according to their estimates, more than 44,000 people had already been infected in Wuhan, with more than 25,000 showing symptoms — a number that may double in less than a week. In addition, their research showed that self-sustaining human-to-human transmission was already happening in all of mainland China’s major cities.

Gabriel Leung, the university’s lead researcher, recommended that “substantial, draconian measures limiting population mobility should be taken immediately” in China, including school closures, remote-work arrangements, and the cancellation of mass gatherings. On Tuesday, Hong Kong instituted new restrictions limiting travel to the territory from mainland China.

The other question is how cases of 2019-nCoV will be severe enough to be detected at all. If people infected with the new coronavirus only show mild symptoms, or none at all, they are unlikely to end up counted among the total number of cases.

How dangerous — and lethal — is the new coronavirus?

Those made ill by the 2019-nCoV coronavirus have developed flulike symptoms, including a severe cough, fever, body aches, and breathing difficulties. Gastrointestinal symptoms have also been reported in some instances. The most severe cases have led to pneumonia or lesions on the lungs. As with most respiratory illnesses, the young, elderly, or those who have a weakened immune system are likely to be most at risk for developing the more severe infections.

At least 106 people have already died from the coronavirus, all in China, but the real danger of the virus has not yet been conclusively determined. Health authorities in China reported on Monday that roughly 17 percent of the confirmed 2019-nCoV cases in the country were severe illnesses, and 3 percent of the cases resulted in death.

But if the total number of cases is far higher than the number of confirmed cases — as many experts are theorizing — it is too early to accurately gauge 2019-nCoV’s severity in either direction.

For comparison with previous coronavirus epidemics, SARS had a mortality rate of about 10 percent, and the mortality rate of MERS, which was not as easily transmissible between humans as SARS, was roughly 35 percent.

The mortality rate of the flu — which kills hundreds of thousands of people around the world every year — is 0.1 percent.

How easily — and when — is the coronavirus transmitted?

One critical factor, when it comes to the threat of 2019-nCoV or any infectious disease, is how easily it is transmitted, and when. This determines how easy it is for health authorities to detect and contain new cases of the virus.

The available evidence already indicates that the Wuhan coronavirus can be passed from person to person like other respiratory illnesses. According to a “tentative clinical profile” of the outbreak at Foreign Policy by doctor and public-health researcher Annie Sparrow, 2019-nCoV is “too big to survive or stay suspended in the air for hours or travel more than a few feet,” but is still easy to transmit:

Like influenza, this coronavirus spreads through both direct and indirect contact. Direct contact occurs through the physical transfer of the microorganism among friends and family through close contact with oral secretions. Indirect contact results when an infected person coughs or sneezes, spreading coronavirus droplets on nearby surfaces, including knobs, bedrails, and smartphones.

She adds those droplets may also be aerosolized during medical procedures, resulting is “super spreading” where one person can infect multiple medical staff members, which happened during the SARS outbreak.

The key question is whether or not the new coronavirus can be transmitted by people who are showing no symptoms of the illness — thus making the infections far more difficult to contain.

In the previous coronavirus epidemics involving SARS and MERS, people infected with the viruses were only contagious when they were showing symptoms, making them easier to quarantine and limiting the viruses’ reach. But China’s health minister has said that there is evidence 2019-nCoV has been transmitted from people without any sign of symptoms. It’s not yet clear how often that has been happening, but it’s a major ongoing concern.

When scientists and public-health officials estimate how easily a new infection will spread, they try to determine the outbreak’s reproduction number, or R0 (“R naught”) — the average number of people who will catch the infection from someone else who has it. So any infection with an R0 higher than one would be something to worry about.

Estimates of 2019-nCoV’s R0 have ranged from 1.4 to as high as 5.5, and the higher estimates have already triggered some panic. But as Ed Yong explained at The Atlantic on Tuesday, R0 is a poor indicator when it comes to communicating the real threat of an outbreak to the public, particularly at such an early stage. Currently, the R0 estimates for 2019-nCoV are consistent with previous coronavirus outbreaks like SARS and HIV (4-5), but far below an infection like measles, which has an R0 of 12-16. In addition, a higher R0 does not necessarily mean more dangerous or transmissible diseases for a variety of reasons, including how difficult the number is to accurately calculate.

Another factor is the length of the coronavirus’ incubation period, which is the amount of time between a person’s exposure to the infection and when their first symptoms appear. A shorter incubation period limits the time heath-care authorities and workers have to detect and isolate new cases, which is particularly important if people are most infectious after they show symptoms. So far, the incubation period of 2019-nCoV has ranged anywhere from two to ten days, but it’s not clear what the average rate will ultimately be. For comparison, SARS had a four- to five-day incubation period.

Lastly, 2019-nCoV will likely continue to mutate as it evolves and adapts to its new human hosts, which could make the illness more or less severe or transmissible.

How can this new coronavirus be prevented, detected, and treated?

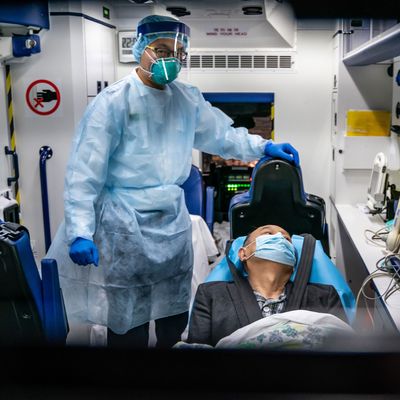

Regarding physical barriers to transmission, proper hand hygiene and the use of gloves, masks, goggles, and medical gowns will reduce the risk of infection in the event someone is exposed to a person with 2019-nCoV.

Detecting the new coronavirus is not easy, however. Health officials in China and elsewhere have been trying to identify anyone with a fever, and then investigating their potential exposure to 2019-nCoV. But there are numerous illnesses that can cause a fever, and there already appear to be a shortage of test kits in the country, and no tests — at least yet — that can return results in less than several hours.

There are also no approved drugs to treat coronaviruses, and if a vaccine can be developed for 2019-nCoV, it could be months away at best. That means that for now, health-care workers can only make sure that infected patients receive supportive care while their immune systems try to fight off the illness.

Will China’s massive response work to contain the virus?

As of Monday, more than 50 million people were effectively under quarantine in China, where the government has shut down travel to and from Wuhan and more than a dozen other cities in Hubei province. Travel into and inside other cities has also been restricted, included in Beijing. The outbreak and quarantine have come during the Lunar New Year holiday in China, when hundreds of millions of people typically travel to visit family in and outside of the country. China has extended the holiday until February 2 in an effort to prevent travel during this critical time.

The outbreak is already a great strain on China’s health-care system, and Stat News reported on Sunday that some infectious disease experts now fear that the country’s efforts to contain the Wuhan coronavirus will not be effective.

Allison McGeer, an infectious-disease specialist in Toronto, warned Stat that “the more we learn about it, the greater the possibility is that transmission will not be able to be controlled with public-health measures” and may thus become a virus that humans will need to learn to live with.

There are also concerns about how many people were able to leave the quarantine zone before it was implemented. The mayor of Wuhan has estimated that as many as 5 million people may have traveled out of the area before it was locked down.

What about the risk in the U.S.?

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on Monday that the current risk to the American public is low, and that there are no signs that the coronavirus has been spreading inside the U.S. The CDC still considers the outbreak a serious threat, however, and on Monday night the U.S. recommended that Americans avoid travel to China.

As of Tuesday, there have been five confirmed cases in a total of four states, all apparently involving people who had traveled from China. The CDC is also investigating another 110 people in 26 states, and it began screening passengers from Wuhan at five airports over the weekend, examining roughly 2,400 people. That screening program may be expanded to arrivals from other cities in China soon.

And though it may come as little solace to many Americans, President Trump tweeted on Monday that his administration was “strongly on watch” regarding the crisis, and has offered U.S. assistance to China.