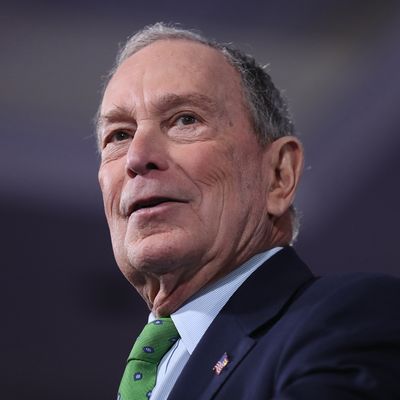

Joe Biden lost his second primary in decisive fashion on Tuesday, failing to win a single delegate in New Hampshire after finishing an underwhelming fourth place in Iowa. His consequent fall in national and state polls has accompanied what seemed to be two implausible prospects as recently as last month: not just the rise of Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire Republican-turned-Democratic New York City mayor, but Bloomberg’s credible challenge to Biden’s heretofore dominant hold on black voters. A Quinnipiac poll published on Monday found that the billionaire had leapfrogged Bernie Sanders among black Democrats, notching 22 percent support to Sanders’s 19 and Biden’s still field-leading 27. Bloomberg has accomplished this primarily by tapping the closest thing he has to an interminable resource: his own vast fortune, which has allowed him to flood America’s airwaves with campaign ads and hire hordes of staffers in states spanning the primary calendar.

As if the ability to buy his way into the election weren’t enough, Bloomberg has been aided by co-signs from several of the black liberal intelligentsia. The most recent was Representative Lucy McBath, the Georgia congresswoman whose election flipped a Republican stronghold in the Atlanta suburbs in 2018. “I first met Mike when I was searching for ways to fight against the dangerous gun laws that ripped my son from my life,” McBath, whose son, Jordan Davis, was murdered by a racist vigilante in 2012, said in a statement, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “Mike gave grieving mothers like me a way to stand up and fight back. Nobody running for president has done more for the gun violence prevention movement than Mike.” McBath’s endorsement was predated by glowing words from Henry Louis Gates Jr., the esteemed Harvard professor and historian. “Among all the candidates, the person who I believe could stand toe-to-toe, strongest and longest with Donald Trump is Mike Bloomberg,” Gates told the New York Times Magazine in early February. MSNBC anchor Joy Reid similarly touted Bloomberg’s status as a former Republican official to convey his singular advantage in out-dueling the president. “If you want a Democrat to win, they have to know how to fight like a Republican,” she said on Tuesday. “[Bloomberg] is a Republican, or used to be anyway.”

The serious consideration that Bloomberg is receiving from some black pols, pundits, and voters — specifically older and more centrist ones — might seem incongruous with his mayoral legacy. It’s been widely presumed that a candidate’s criminal justice record had the potential to devastate their odds in the current Democratic primary. Kamala Harris’s and Amy Klobuchar’s records as prosecutors and Biden’s as an architect of some of America’s most severe federal sentencing laws in the 1990s were thought to be vulnerabilities come nominating time, owing perhaps to how prevalent black-activist pressure on candidates seemed to be in 2016. But while Harris has since dropped out and Klobuchar continues to flounder in the polls, neither of their struggles seems noticeably attributable to backlash against their zeal for imprisoning people. Biden’s record has harmed him even less: Not only does he persist as one of the top two candidates in national polls, he has never trailed among black voters and is particularly strong with those 65 and older, with whom he enjoyed a whopping 68 percent support rate as recently as January.

How Bloomberg’s record might play is therefore surmisable. Though he remains infamous for the “stop and frisk” practices employed by his NYPD — which gave police officers broad discretion to detain and search residents they deemed suspicious, nearly all of whom just so happened to be black or Latino — there’s little indication it’ll be a dealbreaker for many black voters in 2020. Some observers will attribute their amenability to pragmatism; black Democrats coalesced around Biden not just because of his ties to black communities and imprimatur as vice-president to Barack Obama, but because his moderate politics suggested he’d be an easier sell to a general electorate that elected Trump than a leftist firebrand like Sanders. Bloomberg’s foray into the race is indivisible from Biden’s senescence. The resulting lack of an outstanding centrist candidate who wouldn’t impose high taxes on Bloomberg’s fortune makes the ex-mayor a natural fit to assume the former vice-president’s lane should he continue to falter. But an equally compelling case for Bloomberg’s rise among black voters has to do with the nature of his best-known transgression. Understanding “stop and frisk” as disqualifying requires the belief that subjecting black and brown communities to constant police surveillance and harassment in the name of crime reduction is morally indefensible. And evidence of such a consensus is hard to come by — even among many black Americans.

Examples abound: Even black Democratic leaders who expressed misgivings about the potentially negative impact on their communities of the 1994 Violence Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act concluded by and large that exposing black people to harsher law enforcement was an acceptable tradeoff for legislators treating crime with the seriousness they felt it deserved. The irony was that this approach was also unserious. Dating back at least to the 1960s, Democratic lawmakers have responded to black communities’ calls for social investments by partnering with Republicans to impose over-policing and criminalization instead. The Clinton-era 1990s were no different, with white Democrats more than compensating for their black colleagues’ hesitance. Mass incarceration is their collective legacy. Bloomberg’s embrace and expansion of stop and frisk — which he did not invent, and which predated his tenure as New York’s mayor, which ran from 2002 to 2013 — was the continuation of a bipartisan and often transracial accord on how to reduce crime rates in big cities. That crime fell in New York even after the policy was vastly reduced undermines this argument. Paradoxically, the safety and well-being of black people in communities marked for these criminal crackdowns was undermined by errant, humiliating, and often violent police occupations imposed in the name of preserving their safety and well-being.

That Bloomberg has felt compelled to apologize at all for — and even lie about his culpability in — stop and frisk is a testament to how vocal and persistent black and brown New Yorkers, reform activists, and legal advocates have been in keeping it in the public eye. Bloomberg said he was sorry in November. “I was wrong,” he told a black megachurch in Brooklyn. This week, in response to footage recirculating from an Aspen Institute speech in 2015 where Bloomberg justified the practice’s racial asymmetry, he touted having “cut it back by 95 percent” by the time he left office — even though most reductions were in response to a federal judge deeming it unconstitutional, a ruling that Bloomberg fought tooth-and-nail against. There is, of course, plenty more to find alarming about the billionaire’s ascension up the 2020 ranks. His longtime maintenance of hostile work environments for women and repeated legal and anecdotal claims of sexual harassment against him are but two. He also presided over a crucial phase in New York’s makeover into a haven for rich gentrifiers at the expense of those further down the income ladder who could no longer afford to live there. But his major asset, aside from a personal war chest that can sustain him indefinitely no matter how many primary states he loses, is that the people to whom his policies have done the most harm are those whose well-being is considered the most negotiable. This includes in the estimation of large shares of Democrats, including black ones, even as Trump’s racism persists in scandalizing them. Stop and frisk is unlikely to derail Bloomberg’s barreling candidacy mostly because there’s no consensus that terrorizing poor black and brown people into submission is bad.