Almost four years ago, I sat on a cable-news set waiting for the Supreme Court to hand down a ruling on a Texas abortion law that, reputable medical organizations agreed, amounted to a bogus justification for shutting down abortion clinics. The live feed was trained on candidate Hillary Clinton’s Cincinnati rally, featuring Elizabeth Warren, who had just endorsed her.

Alike in blonde bobs and jewel tones, if not much else, the two raised their clasped hands to the sky in a show of party unity and the hint of an all-female ticket, or at least a future in which reproductive autonomy, along with everything else, didn’t depend on the whims of a tiny number of white men. The particular man we were waiting on that day was Justice Anthony Kennedy. Minutes later, the networks cut away to announce that his vote in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt would keep the clinics open, ruling that the Texas law placed an unconstitutional burden on women.

Much like the triumph of progress suggested by the Clinton–Warren stage, though, the moment would prove fleeting. That very win on abortion, and one the year before on same-sex marriage, lulled some liberals into complacency: That fall, exit polls showed Clinton lost in part because conservatives were substantially more motivated by the prospect of stacking the bench with sympathetic lifetime appointments than liberals were. And two years later, Kennedy allowed the president who promised to overturn Roe to replace him with Brett Kavanaugh; both president and the new justice have been accused by multiple women of sexual assault and harassment.

And so we find ourselves this spring in the judicial version of Groundhog Day, in which the Court has agreed in June Medical v. Russo to consider the constitutionality of a Louisiana law that is essentially identical to the one it rejected just three years ago. As Texas did, Louisiana has imposed a seemingly innocuous regulation on abortion providers, requiring that they obtain admitting privileges at local hospitals, that in reality sets them up to fail. Many red-state hospitals outright oppose abortion, fear controversy, or — because abortion is so safe — figure abortion providers won’t be able to meet a minimum number of patient admissions. In Whole Woman’s Health, the Court’s majority ruled there was “no significant health-related problem that the new law helped to cure,” but rather harmed women by reducing access to clinics. Shreveport’s Hope Clinic, which is challenging the Louisiana law, now sees over 3,000 patients a year, but according to the district-court judge’s opinion, in the last 23 years, only four patients had to go to the hospital with complications. Louisiana, it bears noting, already has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the country, a rate grossly higher for black women.

The Court’s ruling will reverberate not only there but anywhere doctors are unable to convince hostile hospitals to grant them credentials, and that would just be the beginning. “If the Court doesn’t hold the line on its own ruling, the floodgates are going to open to more restrictions,” says Nancy Northup, president of the Center for Reproductive Rights, which is arguing the case. No one has asked the Court to overturn Roe v. Wade or make all abortion illegal, but if you can’t get an abortion legally in half the country, Roe doesn’t mean much.

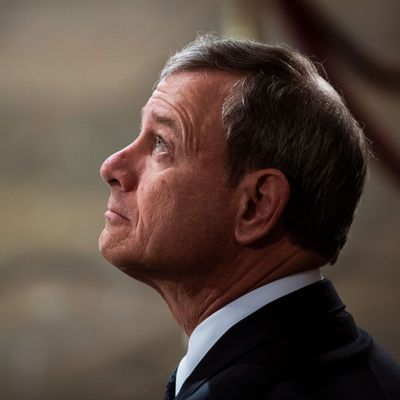

In 2016, Barack Obama’s Justice Department argued forcefully against Texas’ law; this January, the same department came out strongly in support of Louisiana’s version and urged the Court to overturn its own precedent. The clinics and their attorneys’ only choice is to appeal to swing justice John Roberts: a devout Catholic, who came up through the Reagan administration, whose wife sat on the board of Feminists for Life and who has never voted against an abortion restriction.

The pro-choice side’s thin reed of hope is for another rare Roberts apostasy, like his two unexpected votes to save the Affordable Care Act in 2012 and 2015, or in the past term, when he reportedly switched sides at the last minute to block the Trump administration from asking about citizenship on the Census, which was expected to suppress Latino participation. The chief justice has only once broken ranks on abortion, in an earlier, procedural round of the Louisiana abortion case a year ago, when the clinics appealed a Fifth Circuit opinion that boldly disregarded the 2016 precedent; his vote allowed the clinics to stay open for a while. (Kavanaugh dissented, claiming that even though the doctors had been trying for years to get admitting privileges, they could try for a little longer.)

Roberts may have simply wanted to make clear that the Fifth Circuit had gotten too big for its britches and that only the Supreme Court could overrule itself. But an appeal to institutional order might be enough to save the clinics. That’s why the clinics’ attorneys write in their brief, “If the fundamental rules of the road are not honored in our most contentious cases, then the public and political branches may cease respecting the courts as true guardians of the rule of law.” It’s why, along with the stacks of amicus briefs from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Medical Association saying Louisiana’s law will only harm women’s health are ones from the American Bar Association and various federal scholars, essentially arguing that “adherence to basic rule of law principles” are at stake, with the implication being that the Court’s legitimacy rests on not overturning Whole Woman’s Health so hastily. Roberts is supposed to care about this stuff, however much the five Republican-appointed justices have become a rubber stamp for extraordinary requests from the Trump administration, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor recently pointed out.

The driest, seemingly most esoteric question the Court is being asked to resolve could have the most sweeping real-life impact. For almost 50 years, abortion providers have been allowed to challenge abortion restrictions using “third-party standing” on behalf of their patients. This way, abortion providers — who are more likely to be willing to spend years of their lives battling in court — have been able to step in for patients who don’t have the time, money, or connections to defend their rights. But the latest gambit in a long-running anti-abortion campaign to portray legal abortion providers as crooks out to exploit women, is to argue, as Louisiana does, that there is a “senior conflict of interest” between abortion patients and the providers who serve them. In reality, almost all abortions are safer than any number of unremarked-upon outpatient procedures and 99 percent of abortions result in no complications.

There is no crisis of abortion safety; there is, however, a crisis in abortion access. Stephannie Chaffee, an assistant administrator at Hope Clinic, remembers that there were seven abortion clinics in the state when she joined it in 2008. There are now three, and the number may dwindle to one. All this is a widening example of what Yale Law School’s Reva Siegel and Linda Greenhouse call “abortion exceptionalism,” the set of special rules around abortion laws that substitute moral disapproval for medical judgment and seek to blur the difference. That’s a heavy burden for any individual patient to shoulder. Says Chaffee, “We ask patients to tell their stories. They’re so hesitant because of the stigma. They just want to get it over with,” not participate in a lawsuit. If the Court says clinics can’t challenge laws on behalf of their patients, says Diana Kasdan, director of judicial strategy at the Center for Reproductive Rights, “it would be shutting down the courthouse doors.”

The anti-abortion movement may sincerely dream of shutting the courthouse doors to abortion clinics, forcing individual patients to do battle with the system. Or it could be political gamesmanship. Asking the Court to consider the extreme possibility now may be a strategic move by the right, giving Roberts the chance to feign compromise. It’s worth pointing out that in 2016, Clarence Thomas was alone in claiming in a dissent to Whole Woman’s Health that doctors and clinics couldn’t sue on behalf of their patients, and Louisiana only added this argument after the clinics appealed to the Supreme Court six years into the litigation. A loyal Republican, Roberts surely understands that making a radical move on abortion once again just months before a presidential election might mobilize the ever-awakening opposition — a short-term win for a long-term cost. And so, like the diner picking the mid-price wine, he could split the difference, letting the law go into effect while rejecting the premise that doctors and clinics can’t sue. The headlines might again call the chief a sage compromiser. The notion that Roe v. Wade hadn’t been overturned would set up advocates for reproductive rights to once again be accused of crying wolf. It would blunt the resistance among the sleeping pro-choice majority, taking the heat off the Court just as the middle-of-the-road voters are contemplating whether another Trump term would really be that bad.

But allowing any part of Louisiana’s argument to become law would be no rhetorical exercise. It would have a devastating effect on millions of people. If that happens, don’t be fooled — Roberts will be making a choice.