This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

The morning after President Trump delivered his self-congratulatory State of the Union speech while still in the midst of impeachment, several reporters are waiting in a Providence, Rhode Island, vegan café for Michael Bloomberg. Most of them came from Philadelphia last night, where they covered his nighttime rally that had a laser-light show, buffet, open bar, and rap performance. Like the rest of the media at the time, they have been caught up in a kind of fever dream in which, suddenly, in the brief interval between the Iowa collapse of Joe Biden and the appearance of Bloomberg himself on a Nevada debate stage, it seems possible that a plutocrat could waltz his way to the Democratic nomination as comfortably as he had to the New York City mayoralty, including an extralegal third term. How plausible a fever dream? The reporters are themselves unsure. One of them, picking at a coconut-yogurt-açai-organic-oat bowl, asks somewhat idly, “Were there real people there last night?” — meaning, was it stocked with paid Bloomberg staffers and spouses and neighbors or were the bodies in the hall actual Bloomberg supporters? “They were real people,” says a tall cameraman, cocking his head. “It was kind of amazing.”

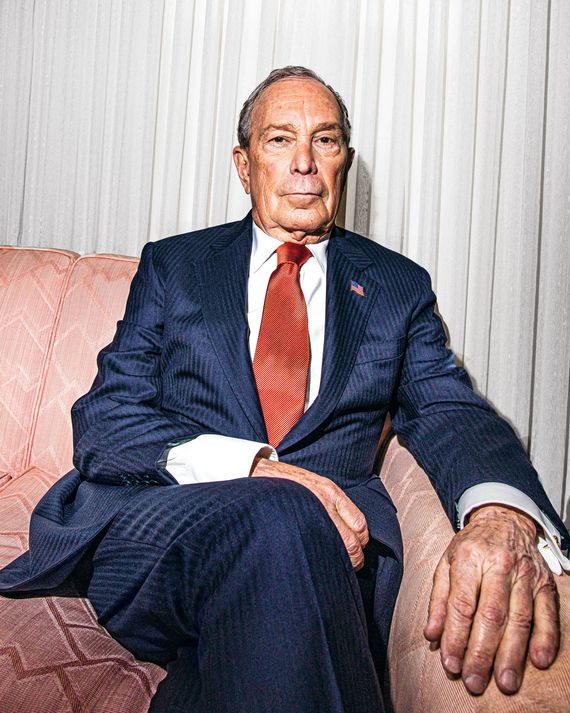

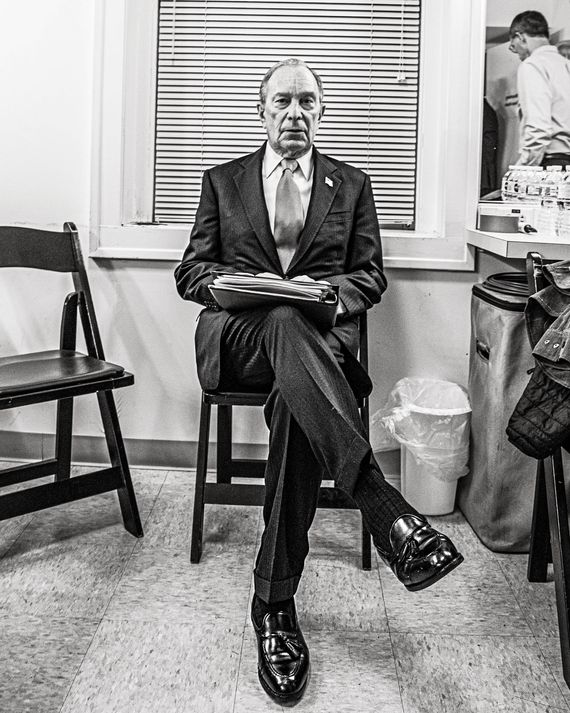

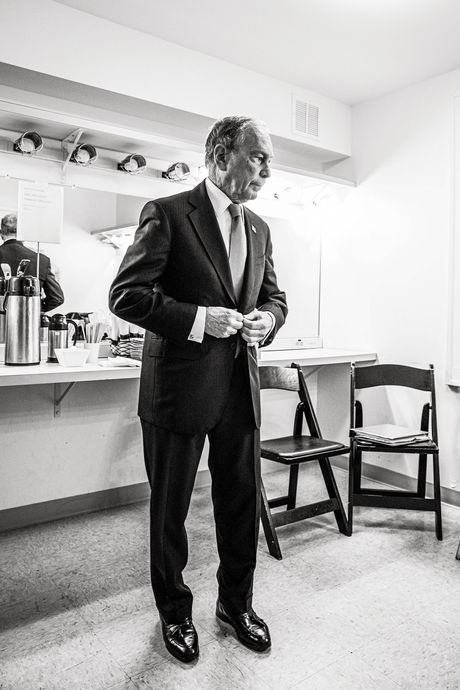

Nearby, the would-be savior of the Democratic Party is resting in a car. Punctual and perfectionistic, the kind of guy who has advised people not to take bathroom breaks and once said “I don’t have anything in common with people who stand on escalators,” Bloomberg had arrived early in his plane and soon strides up to the café alongside Rhode Island governor Gina Raimondo, a former venture capitalist who is about to become the first governor to endorse Bloomberg. The former mayor is a slip of a man in black tasseled leather shoes. One could call his suit navy, but it’s somehow more refined than the color implies and so well cut one imagines a tailor adjusting a small seam when he gains or loses a pound. His face’s central plane — nose, cheeks, brow — is flat, but around his jowls, skin creases like a Chinese paper fan. He smiles only occasionally and not with his mouth. Like many extremely wealthy men born in the mid-20th century, he comes off somewhat effete, his hands making small, gentle gestures even as the tone of his voice veers from low-gear chattiness to swashbuckling machismo.

Raimondo and Bloomberg inch toward a counter to buy coffee as his team scurries into position — an advance man in a spotless suit who mentions John Mellencamp just endorsed Bloomberg; a recent grad in pearl earrings who now isn’t sure she can take a post–Super Tuesday vacation to Tulum. As the cashier shoots Bloomberg a wary look, he picks up a packet of gluten-free energy balls. “Will I feel better afterward?,” he asks. He reaches into his pocket for a nondescript black wallet, from which he does not take out $60 billion, but merely a $20 bill, and leaves a healthy tip.

“Well,” he says, turning to the restaurant’s owner, “we got back late from Philadelphia, then I unpacked because I was away for four or five days, and by the time you put everything back,” he trails off. “And I read for a few minutes. Which was a mistake. So I could use some more energy.”

The owner begins evangelizing about plant-based nutrition and opening a location in New York City. Then Bloomberg just starts to talk. “I was up in Maine and Vermont recently — look at the foliage and that kind of thing,” he says. “They have a diner we go to. The food was really good. I said, ‘We should have those diners in New York.’ We’ve had a lot of diners close. It’s partially tastes have changed, but we’ve had four restaurants in my neighborhood close in the past six months. Each one was in a townhouse. They’re ripping them down and putting up these thin slivers of buildings. There’s one two doors away from me. I had the developer and his wife over for dinner. He said they’re getting $3,000 a square foot for 4,000 square feet — one floor, 12 million bucks! He took the top floor for himself, and he thinks he’s going to move in.”

“Nobody could pay that rent,” somebody pipes up.

“Uh,” says Bloomberg, pausing, only a little self-consciously. “Y’know …” Then he motors on. “And the Upper East Side has become less fashionable, supposedly.”

This kind of monologue — weird, unguarded, almost like it was scripted to illustrate out-of-touchness — is exactly what every political strategist in America pointed to when Bloomberg considered running for president in 2008, and then again in 2012, and then again in 2016. That guy could never win in America, they said — not the pasha of the Upper East Side, as important in his way to the city as the Astors and as foreign to actual voters. But Bloomberg has loomed as a David Koch–like figure in the Democratic Party in recent years, spending $65 million on the 2016 election and over $112 million on the midterms two years later — meaning he is now not just one of two or three or four serious Democratic candidates for president (depending on how you count) but also, in recent history, the party’s most important benefactor and donor.

In 2019, he gave $3.3 billion away, more than Trump’s entire estimated net worth of $3.1 billion — and the largesse has apparently made everyone very happy to see him at almost all times, which may have given Bloomberg the idea that a presidential campaign could feature more of the same. Yet those who know him best have often thought it wouldn’t be easy. “Mike is not going to arrive as JFK reincarnated,” says Tom Brokaw, an old friend. “That’s not who he is. He’s a different cat altogether.” Joanna Coles, a television producer and the former chief content officer at Hearst, says, “He’s hypercurious, supersmart, and restless. I think the restlessness is key. It’s what makes him such interesting company.” But restlessness isn’t exactly a presidential quality. An ex-employee argues, “The thing about Mike is he actually isn’t that interesting — he’s smart, and you can have a good time talking to him, but it’s like talking to any old Jewish relative of mine. The first time I met him, he started complaining about some soup he got that didn’t taste right. I just met the guy, and he was, like, complaining about his sweet-and-sour soup.”

In Providence, Bloomberg pulls out Raimondo’s chair for her, to sit for coffee, then deadpans that he had to do it or “my mother would shoot me.”

“What should we be talking about that they could overhear by accident?,” Bloomberg asks showily, gesturing to the cameras, but doesn’t wait for an answer. “The crowds are getting bigger and the number of reporters,” he muses to Raimondo. “You can tell what editors think when they send them. They think we’re going to win all of a sudden or have a good chance. So they’re all showing up.”

“You have a chance,” Raimondo says. “Better than a chance.”

The beginning of February 2020 may be remembered mostly for the global spread of a lethal virus, but close seconds may include the nearly unanimous Republican vote against impeachment in the Senate, followed by Trump’s victory tour of firings and pardons; the possible erasure of Iowa and New Hampshire’s pride of place on the electoral map; and the launch of one of the most quixotic, expensive, and risky presidential campaigns in our history. Bloomberg’s case, beyond climate change, gun control, and urban renewal, rested on an electability argument — that defeating Trump was an absolute necessity and that a technocratic moderate was a safer bet than a democratic socialist. But in the space of two weeks, his campaign had seemed to damage moderate Biden’s prospects and dramatically elevate the temperature of conflict between the party’s progressive and Wall Street wings, all without managing much headway on his own candidacy. By the end of February, the ride looked to be about over — or at least poised to come to a halt on Super Tuesday, after two weeks of pile-ons from Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, an increasingly ugly and almost unending archive of oppo research (previous comments about how cops could Xerox pictures of minorities to find criminals or suggesting Mitt Romney would be a better president than Barack Obama) and an absolutely dead-eyed first appearance before a national audience, in which Bloomberg didn’t seem to have anticipated needing to answer any of the most obvious criticisms and whiffed his jokes. But in between, for a brief and glorious moment, it had looked like the New York power and media elite, who are Bloomberg’s natural base, might actually have their way, taking the most important presidential election of any of our lifetimes into their own hands — and collecting some huge consulting paychecks in the process.

Bloomberg officially announced his candidacy on November 24, signaling immediately that he’d skip the first four states and just focus on the races beginning Super Tuesday. The Iowa-caucus counting app blowing up on February 3 was the stroke of luck Bloomberg needed to move up in the polls, after which he smartly capitalized on the chaos by doubling his ad spending (“Obviously a flex,” as one of his staffers jocularly put it to me). Bloomberg had bet on no clear front-runner coming out of Iowa, then Biden getting soft, then the moderate lane falling apart, then Sanders or Warren arising as the default victor, then a collective buyer’s remorse that would allow him to swipe the victory out of his or her hands. But this was better than in his dreams. And it came so cheap! Bloomberg’s self-funding was $5.6 million per day. Given that Bloomberg’s fortune earns $107 million per day, according to the Washington Post, he could comfortably go a lot higher still. (Biden, then the putative front-runner, had raised $8.9 million in all of January.)

Before the Nevada debate, some aides had put out the word that even if Bloomberg performed poorly — which he would, they said, so please lower expectations — the moderate wing of the party should line up behind him, given his money spigot and all. He had publicly floated the idea that he might spend $1 billion on the November election whether he was the nominee or not. Whispers within the campaign suggested his actual ceiling was $4 billion. By the end of the month, it seemed he might have to spend that much to save the party from the disarray he had himself helped create, in part by complicating the candidacy of the one moderate who actually had a shot, Biden, while clearing the way for Bernie to march to the nomination with 35 percent support.

Until the debate, the question on everyone’s minds had been “Can the presidency be bought by the ninth-richest man in the world?,” to which the answer seemed to be “Yes, possibly.” He had even briefly managed to turn the caricature into a sort of strength, at least for niche audiences, churning out a raft of weird social-media memes that it took the internet’s cool kids a few days to figure out but that amounted, ultimately, to Mike leaning into a reputation as an out-of-touch moneybags. But that was a kind of managed image, and the debate was disastrously unmanaged — as was the South Carolina reprise, though measurably less embarrassing. Afterward, the question became “Can the presidency be won by someone with negative charisma?” The answer to that was much less certain. After all, Trump performed a similar end run around the Establishment in the last presidential election, but he also knew how to command the camera, and who could stop rubbernecking whether one regarded him as a demigod or car crash?

So why did Bloomberg run? Love or hate him, he is an exceedingly rational creature, and, over the summer, his team identified a teeny-tiny crack in the door that opens to more power than anywhere in the world — about a 5 percent chance of gaining the presidency, I’d heard — and thought they’d try to wiggle through. Bloomberg had been under the impression that Biden had the moderate lane covered when he declared that he was skipping a run in March 2019. But Bloomberg spent the summer in the dumps (golfing, grandkids, no longer jogging but doing a lot of speed walking), increasingly anxious about another four years under the thumb of a man who had been the laughingstock among his elite friends for decades upon decades. Try to put yourself in the shoes of a $60 billion ego: If one had Bloomberg’s fortune, and Bloomberg’s resolve, and did not at least try to destroy the Cheeto with his own bare hands, what would that mean to history? Trump worked against the cause of progress, Trump was bad for the planet, Trump was a threat to rationalism, Trump revealed his indecency in Charlottesville, and who knew what terrifying animal spirits he’d stir up next? “Mike once said to me, ‘The only way the Republicans abandon Donald is if he fucks a child or wakes up in bed next to a dead person,’ ” says an acquaintance, putting his spin on Louisiana governor Edwin Edwards’s famous old line. The campaign responds, “Mike does not remember saying this.”

Throughout 2019, Bloomberg, like many older politicians also feeling their mortality, John Kerry among them, watched as Warren became the presumptive nominee, then faded, and looked again at Biden and thought, How is this guy this bad, and this broke, and still winning? For years and years, Bloomberg had an apparatus continually monitoring his chances — maintaining, just as a kind of casual, on-the-side, not-so-serious exploratory team, as big a campaign as most candidates would have as they approached the Iowa caucuses. He also gathered intelligence anecdotally, canvassing his clique. “We had a couple pretty long conversations, with me quizzing him and him trying to get an evaluation for what the odds were,” says Brokaw. “The more he looked at it, the more he thought, I do have a shot. And the more he felt a civic obligation.” “My dad often tells me regret is not an emotion that he has,” says Emma, Bloomberg’s elder daughter. “I’m not sure how that’s possible!” But the interregnum between saying he wouldn’t run in March and then declaring he would indeed run in November was “the first time in my life that I would have pushed back,” she adds. “I would’ve said, ‘I think you regret making the decision not to run.’ ”

When Bloomberg first announced, facing what seemed like such steep odds Nate Silver was reluctant to even list him among the serious candidates, Democratic insiders suggested that Bloomberg’s team may have sold him a little hard on his prospects, making his shot sound more probable than it was. And Bloomberg’s campaign manager, Kevin Sheekey, regarded as a master of the dark arts and one of the hardest-charging political operatives in the country, did donate $2,800 to Biden, the maximum personal contribution, as recently as June. But within months, Sheekey, a baby-faced guy regularly clad in a baby-blue open-collared shirt (“I literally look at people with ties, even in movies or photos, and think, Who came up with that, and why do you wear it?”), was back on the Bloomberg train. “We presented Mike with data, which I actually did move up a few days because I did recognize what the calendar was,” says Sheekey. If Bloomberg decided to run, even skipping all the primaries before Super Tuesday, his team still needed to file petitions for his candidacy in Alabama right away. “We met with Mike about three days before that deadline, with no real urgency that that was a serious concern — but it was material.”

The next morning at seven on the dot, Sheekey’s phone went beep-beep-beep. “He goes, ‘Hey, it’s Bloomberg.’ I said, ‘Yep.’ He goes, ‘Okay, so I guess we’re going to do this thing.’ Fortunately I was sitting at the time.” Sheekey got on the horn with an advance man in Arkansas, “which struck me as reasonably close to the state of Alabama.” Sheekey told him, “ ‘I need you to get every single person you know into Birmingham by this afternoon.’ He said to me, ‘Does this mean what I think it means?’ I said, ‘It sure does.’ All I heard was, ‘Yahoo!’ ”

As a candidate, Bloomberg sells himself as a management savant who can fix the federal government. Maybe there was a constituency for him: supporter and congressman Ted Deutch of Boca Raton says, “The kind of people I grew up with in Pennsylvania, my neighbors in Ohio, and now in Florida — these folks in swing states who turned up in 2018 to send a message to President Trump — just want a president that lets the country function again.” He certainly built an extraordinary election machine almost out of thin air. Within six weeks, Bloomberg had hired nearly a thousand employees and transformed an empty floor of a neo-Gothic building near Times Square that once housed the New York Times (and is now partially owned by the Kushner family) into his headquarters.

Up in the waiting room, an ad plays on a flat-screen TV about low-income and minority pregnant women and how they die more than white women (but Mike will fix that). Two countdown clocks hang above the TV, one marking the days until Super Tuesday and the other the days until the national election. The folks here don’t seem like run-of-the-mill campaign volunteers; they’re middle-aged political mercenaries in fleece with time-tested strategies and robust Rolodexes. A political consultant tells me, “They’ve hired the whole goddamn world and have a lot of credible people. It’s not like Trump’s first campaign, with people working for him you’d never heard of before — which, by the way, definitely worked.” Bloomberg has recruited from his City Hall and hoovered up people from shuttered presidential campaigns (Kamala Harris, Andrew Yang).

He’s always treated employees to salaries, health care, and bonuses beyond industry standards and is now paying many multiples more than other campaigns, plus free furnished apartments in Manhattan. “This is the kind of campaign we’ll never be on again in our lives!,” exclaims one staffer, incredulous at his new Bloomberg-issued iPhone 11, the free booze, and the three catered meals a day (peeking in the campaign café at dinnertime, I spied pizza and tuna steak). Even the lowest-level campaign workers, like a yoga teacher who says they’re making $6,000 a month just to canvass for him — work that almost every other campaign relies on volunteers for — share some of these benefits.

“As my uncle says, ‘Rich or poor, it’s nice to have money,’ ” says senior adviser Howard Wolfson, an architect of Hillary ’08 and a longtime Bloomberger, usually wearing AirPods in his ears and a Cheshire-cat grin. “Would you pay for people’s Ubers” to get them to the polls?, I ask him. “Sounds like a good idea,” he says, and it’s not entirely clear he’s joking. But you can’t make people vote for you, he says. “I’ll take the Uber and vote for someone else.”

To anyone on the outside, it looked like Bloomberg was trying to buy the nomination, and indeed, he was. People at Bloomberg Philanthropies who’d distributed many of his millions to American cities were the same folks facilitating asks to the same mayors and other legislators about endorsing Bloomberg. And even only half-informed voters could see that it was probably impossible for Bloomberg to win the nomination outright and intuited, therefore, that the mayor’s plan was to drive Democrats to generational infighting at a contested convention in Milwaukee in July, which struck fear in their hearts: If they didn’t unite behind someone until July, the party stood a good chance of losing again to Trump.

Bloomberg must’ve known Democrats would figure this out eventually, and when they did, they’d be pissed — so, partially as a defensive maneuver, he made it clear he was only in this game to defeat Trump, and even if he didn’t secure the nomination, he’d keep up his payroll and also rain millions upon millions on whoever trounced him, which is a crazy move for one of the world’s most competitive people, but he promised.

“You know what’s amazing to me?” Sheekey asks, somewhat rhetorically, as we talk in mid-February in a conference room dominated by a TV with CNN on mute. “I was just talking to somebody who worked for Hillary for a really long time. I said, ‘Where do you want to start? Joe’s campaign’s over.’ She goes, ‘What are you talking about?’ I’m like, ‘Are you kidding me? What are you drinking? You don’t come in fourth in Iowa and fourth or fifth in New Hampshire and go on to win a major party nomination. There’s no historical precedent for it. What are you talking about?’ ”

And then there were the ads — millions of ads. Positioning himself as a friendly new product in the American landscape, like the Geico lizard, Bloomberg carpet-bombed 50 states with television ads and even hired female prisoners in Oklahoma to call to voters via a third-party vendor (the campaign says it was unaware of the arrangement and halted the contract when it was revealed). Gary Briggs, the former CMO at Facebook, is running Hawkfish, Bloomberg’s main digital-strategy team, which has put 2 billion ads so far on Facebook and Google. At a scale unprecedented for political campaigns, which are always playing with so much less cash than the corporate world, Bloomberg has drafted an expansive, best-in-class team of Silicon Valley data scientists, social-media managers, and even executives from his own company, “some of whom are true believers in Mike and trying to save the Republic and some of whom were not really given a choice about joining the campaign,” says a former colleague. “He’s working them like dogs, and they’re like, ‘When can I go back to my nice corporate job again?’ ” (A campaign spokesperson says no employees were forced into a job.) Bloomberg, a believer in open-plan offices, sits in a quiet corner. His head pokes up over his desktop computer, partially obscured by a vase with yellow daffodils. One ex-employee describes getting into a fight with Bloomberg and, regardless of whether Bloomberg has an executive suite in his offices, hearing him bark: “ ‘Don’t forget whose name is on the front door.’ It’s ridiculous,” he says. “Mike’s name isn’t only on the door; it’s on the fucking pencils.”

Beyond the management skills, those who know Bloomberg call him a sun god — when he’s shining on you, all is bright, but wait for the shadow. In Providence, he stands in front of a crowd of a couple hundred in a fancy new civic building dubbed the “Innovation Center” to deliver his usual stump speech to a crowd of mostly white professionals (afterward, I talk to a therapist, a retired engineer, a designer of logos at CVS, and several professors). As they hold up their cell phones to capture the historic moment of a presidential candidate in the flesh in their small and not-at-all electorally important state, he drones on and on. He speaks in monotone with such a flat affect that one’s brain almost cannot process his words as language, but rather white noise with a soothing background whisper of “We’ll do lots of things, it will be great.”

Here and there, he usually tells some jokes. “People say, ‘Do you really want a general election between two New York billionaires?’ To which I say, ‘Who’s the other one?’ ”

Directly to Bloomberg’s left, a bunch of tattooed guys wearing black leather bomber jackets, looking vaguely like the band Foreigner in Red Sox caps, start hollering. “Can you tell us why you’re in Jeffrey Epstein’s little black book?,” one yells.

“Time out, time out,” exclaims Bloomberg, immediately filling with the pep he thought he’d get from the energy ball. “Folks, No. 1, the answer to your question is I have no idea. And if you stop this, I will talk to you outside.”

“You’re a sellout!,” they scream.

“Thank you for making me feel like I was in New York City,” he responds drily.

By ideology and temperament, Bloomberg is a meritocrat with no time for those who might waste his. A libertarian with straight brown hair to his butt and the only–in–Rhode Island name of Elijah Gizzarelli tells me he stayed in the auditorium to meet Bloomberg after his speech. “I said, ‘You said you’d talk to us afterward, and we’d like to take you up on that,’ ” says Gizzarelli. “He said, ‘Well, you can’t talk to everyone,’ and turned away.”

Bloomberg has mostly kept his cool during his candidacy — “I spoke to him” around early February, says Ken Chenault, the former head of American Express, “he is encouraged by the reaction he’s getting, though he also knows it’s going to be a tough challenge” — but he loves a jaunty comeback. And though his humor at the debates came across less as self-deprecating than deprecating of all humanity, he can be quite funny when he’s bitchy. From the beginning, Sheekey and his other top aides advised him to make this an asset, to attack Trump head on, since trading direct insults with the president gives the impression that they are the only two candidates. But it’s also because from the beginning of his campaign, he’s known if he went after other Democratic contenders hard, they might kill him.

A friend says Bloomberg’s deepest self-image, even at 78 years old, is of himself in his mid-20s, in the 1960s, when he was thrust among the blue-collar boors of Wall Street way before the Gordons from Groton showed up. He was the middle-class son of a dairy farm’s bookkeeper from Medford, Massachusetts, with a job as a parking-lot manager to pay tuition at Johns Hopkins who then attended Harvard Business School. Shocked and intimidated by the inherited wealth at HBS, he felt more comfortable on Wall Street. He loved New York, taking an L-shaped studio on the Upper East Side listed for $150 a month that he bargained down to $120. He went to Maxwell’s Plum, the singles bar where Donald is rumored to have met Ivana, and told this magazine he spent his vacations on his apartment building’s roof — “tar beach.”

Bloomberg made his billions in an unsexy business: database terminals for the Wall Street bond market. Though his company, of which he owns 88 percent, expanded into many areas, including media, it remains a data-processing and terminal company. “Mike destroyed every competitor in the terminal game to become a monopoly,” says a former employee. “The terminal is a status symbol — Bloomberg-terminal fanboys rival Apple fanboys and Tesla fanboys.” And while that makes Bloomberg himself a tech mogul, he no longer really plays the part. “If Mike had a problem with his computer or phone, the entire engineering team would run over to his desk,” says an ex-employee. “Then they’d be like, ‘You need to put your phone on Wi-Fi.’ ” After expanding into the news business, he worried over the font size on TV chyrons and exhibited only a cursory awareness of the internet. (His campaign counters that Bloomberg is “deeply aware of technology trends.”) Long-term employees say he seemed to have lost a step when he returned to the business from the mayoralty in 2014, lobbing the notion he should cease publishing a website and saying he was against advertising. An employee argued for ads, saying, “ ‘Well, Mike, what if you were reading, like, a golf magazine and saw some clubs? You might think these are worth getting.’ He was like, ‘No, I’d just ask my golf pro what the best club is.’ ”

It’s incredible that in 2020 anyone still needs a $24,000 dedicated Bloomberg terminal to gather corporate information and trade stocks, but apparently they do. A friend says Bloomberg mostly socializes with the buyers of big terminal orders at banks and old friends, and he even maintains a relationship with Jeff Bezos, whom he likes quite a bit (Bloomberg was privately appalled that New York City wouldn’t let Amazon into Queens, though he also suggested the deal was too generous to the company). A devout kibitzer, he’s a funeralgoer, wedding-speech-maker, and I’m-calling-the-top-oncologist-for-you-er who keeps in touch with many from his past, even those from high school who have fallen on hard times; they hit him up for money, which he finds stressful. But he does dole out. At a New York City fund-raiser, “I was in front of the crowd, waffling on about trees, saying, ‘I always had this dream of planting a million trees,’ ” says Bette Midler. “Suddenly, Mike leapt to his feet and shouted, ‘That’s a great idea! We’re going to do that!’ Everyone stared, aghast. Three beats later, thunderous applause, and a standing ovation, because the whole crowd knew that if he said it, it would get done. And it did.”

As mayor, he famously chose not to live in Gracie Mansion, preferring the comforts of his 79th Street compound, though not everyone is impressed by his old-world décor: “The first time I went to Mike’s house, I was surprised to find the décor very much like a child’s idea of what a rich man’s house would look like,” says an acquaintance. “Very Citizen Kane.” He kept his social life mostly intact, spending weekends golfing at his home in Bermuda. “Mike gets loosey-goosey on wine, visibly shining, but if you really try to get him to open up then, sure enough he gets flustered and retreats into his shell,” says a reporter.

Bloomberg’s children, Georgina and Emma, are opposites. Georgina, 37, is an equestrian and private-plane-flying Instagram bombshell who, when her dad said he wasn’t going to run for president in March, posted a picture of a faux campaign sticker, reading BLOOMBERG: BECAUSE FUCK THIS SHIT, with the caption “officially back to being just our family slogan.” She has lots of animals: “We have a 300-pound pig,” says Mike Bloomberg. “We have a goat who tries to put his horns in your pocket and rip your pants open. We have a pigeon that just moved in, but we also have a rooster who wakes you up early in the morning. We have a mule. We have some horses. Stop me when you get bored.”

Emma, 40, is a policy wonk who runs an education nonprofit. When I meet her in a hotel lobby near Bloomberg HQ, she’s all Tribeca-mom elegance: her brown hair slightly lightened, arms sculpted, and many tiny diamonds adorning her ears and climbing from wrists to forearms. Donald has famously declared he never changed diapers; Bloomberg, ever the egalitarian, didn’t like feeding infants, so took as his solemn duty changing diapers instead. Emma knows Ivanka — they were in an after-school art class in middle school together — but she doesn’t remember her dad talking about Donald Trump before he became president. “I cannot remember ever hearing of him,” she says. “He’s not going to be happy about that. I’m sure he’s supposed to be the subject of everyone’s dinner-table conversation.”

Unlike the Trumps, whose family unit was forged in Donald and Ivana’s miserable marriage, Bloomberg and his ex-wife, Susan, had an amicable divorce in the ’90s and even lived together at times afterward. “People can love each other, can be dear friends, can be supportive of each other in lots of ways and not be meant for marriage — they were very clearly not,” says Emma. “My mother wanted to stay at home, and my father had to be out. As a child, just because you’re young doesn’t mean you’re an idiot, right? You actually do see these things and internalize them.” After the divorce, Bloomberg tomcatted around town and made many comments about women’s figures not at all under his breath. The campaign has recently been rolling out his longtime partner Diana Taylor, 65, a lifelong Republican from the heartland of Old Greenwich, Connecticut, who became a Democrat in 2018. Taylor attended Milton and Dartmouth, started at Smith Barney in the 1980s, and has been New York’s state superintendent for banks. Anna Wintour calls in dresses for her, she loves her Labradors, and she’s on the boards of Citigroup and a micro-lending nonprofit.

This genteel lifestyle — Bloomberg’s planes aren’t very chic, says a friend, “though they have four” — is a direct contrast to the patriarch’s salty language. “His humor is dry, almost too dry, and sometimes it’s over the line,” says Brokaw. “I would say I probably learned every curse word I know from my father,” says Emma. “I have vivid memories of the expletive, expletive, slam!” She pantomimes hanging up a corded phone. “But he never used them at me or with me. That was how he got his stuff done.” Even at his home, during carefully composed dinner parties, he can get touchy. Long ago, during his quest to build a stadium on the West Side, conversation naturally turned to the viability of the project. “I asked a question, as one does at a cocktail party, revealing my personal concerns, and was startled when he interrupted me with the harsh admonition, ‘You have no idea what you’re talking about,’ ” says the head of a nonprofit. “It was a really bizarre moment. I was a guest in his home. Mike was not only not interested in engaging in discussion but devoid of basic manners.” (About this episode, the campaign says, “This person probably had no idea what he was talking about.”)

Bloomberg’s not asking for donations for his campaign — though he’d prefer his friends, the donor class, didn’t give other candidates money either. This is appealing to some folks, but not all. “How much is Mike worth?” says developer Douglas Durst. “A lot of that’s thanks to Trump’s tax policies. So he’s using the money Donald gave him to run.” Durst adds, “He doesn’t need my money. I’m going to support whoever the nominee is.” Even those who may like Trump regard Bloomberg as a civilized alternative: “Donald has done much that will be perhaps considered positive in the future, but he polarizes people,” says Cancer Research Institute trustee Lauren Veronis. “Calling him ‘Tiny Mike’ — well, the people who like Mike get their shoulders up about it.” I ask Emma Bloomberg about the young moneyed class in New York, which, from my casual survey, seemed split on supporting Trump. She mentions being at a couple of dinner parties with friends of hers or her dad’s this summer and having “the question [at the table] be, ‘If it’s Trump or Warren, who do you vote for?’’ The number of people who, if you ask them on any individual policy or social policy, are vehemently anti-Trump, who would say, ‘Well, in that case, I’d have to sit it out,’ or in that case, ‘Yes, I’d have to vote for Trump,’ I found astounding.”

The early stages of the campaign felt, internally, relatively smooth — the race evolving exactly as Sheekey and Wolfson had hoped, the media desperate to believe in the glow of a Bloomberg candidacy. But the same day as the New Hampshire primary, the first bit of oppo dropped: an audio clip about stop and frisk from a Bloomberg talk at the Aspen Institute several years ago. As the story gained steam the next morning, it just so happened some black faith leaders were at HQ for a meeting when Trump tweeted out that Bloomberg was a “TOTAL RACIST.” “The phones of Mike and the faith leaders in the room kind of lit up,” says Sheekey. “Twenty-four to 30 faith leaders around the table’s instant reaction was, ‘We have to do something. We need to call a press conference. We need to endorse Mike Bloomberg now.’ ”

To friends, Bloomberg insists he feels bad about stop and frisk, but he still can’t understand why he’s not gathering applause for gun control. “Mike came into the mayor’s office, black people were dying, and he was like, ‘God almighty, how do we solve this,’ ” says a friend. “What he says privately is, ‘I was sitting with mothers of boys who were being shot. They said their sons were scared in the projects and had guns to protect them, so I thought you’ve got to get rid of the guns. The guns are killing people.’ But he didn’t get the social impact of stopping kids 70 times in high school.” They say he understands the humiliation now — mostly. He’s also a little “Asperger’s-y,” friends say, meaning he doesn’t quite feel others’ pain.

Then the Washington Post got its hands on a booklet of “Wit and Wisdom” Bloomberg’s employees had put together to celebrate-slash-roast their boss in 1990 — a pamphlet actually located by Fire and Fury author Michael Wolff for this magazine in 2001. “I wrote about it on Monday, September 10, and the next day, the story was forgotten,” says Wolff. “The towers were crumbling and I’m going, ‘My scoop, my scoop!’ ” Bloomberg’s grotesque alleged phrases pinged around the world, along with the old news that he’d told an employee newly pregnant to “kill it,” which is quite a bit of dry humor indeed.

When I ask Wolfson about Bloomberg and women before the first debate, he waves questions off. “Allegations, news reports,” he says. “There’s no one who runs for president who doesn’t have to deal with some negative information that’s disseminated or reported upon — that’s table stakes, that’s my day at the office.” Taylor was reportedly even more unemotional: “It was 30 years ago, get over it.” But misogyny is another case where Bloomberg seems to kind of get it and kind of not. He has argued that in the case of Charlie Rose, whose TV show taped in his corporate offices and who, according to two individuals, did not pay rent, courts should decide. He has many capable women around him, yet he’s known for making lascivious comments that are totally out of bounds. Ginny Clark, the first woman in Salomon Brothers’ training class, sat next to Bloomberg in 1968, and considers him a mentor. “The things that happened to me,” she says, trailing off. “Honestly, I’ve never sued through my whole life, or never wanted to, because I felt I will rise above it, which luckily I always did. You know, today, for a hug they’ll sue you.” Clark paints a picture of the stockbrokers’ lifestyle of yore — an in-office barbershop and waiters in black tie bringing around lunch on china so traders never had to leave, people who would “slam phones, scream, yell, strippers, you name it, it would go on.” What did Bloomberg do during all of this? “I won’t tell you some of the things they tried on me, but it wasn’t Mike — it was some of the others. He was there, kind of like making them back off some,” she says.

As the oppo fell from the sky like rain, true believers tried to spread calm. “Mike inspires incredible loyalty,” says Dan Doctoroff, one of his lieutenants for years and the founder of Sidewalk Labs. I also talk to Fatima Shama, Bloomberg’s commissioner of immigrant affairs. Wearing a lanyard with an I LIKE MIKE button, she describes creating the “culture that is Bloomberg” at HQ, with its grab bag of politicos and social-media managers from all walks of life. “I have said to people here who have had an abrupt tone, ‘Try again.’ And they’re like, ‘Excuse me?’ And I say, ‘We don’t speak to people that way here. Try again.’ ”

On the campaign, Shama leads outreach to minorities and women as the head of constituencies and coalitions. But would Sanders take better care of these folks? “There’s no record of Sanders ever doing that,” she says. She calls Mayor Pete a “38-year-old who can’t actually lead. He should run Indiana, because we could use that.” And when Shama talks about raising three Muslim boys in the Trump era, her eyes become misty — crying from what seems less like sadness than righteous anger. “I know what a Bloomberg administration did in my city and for people — the very people I have worked with my entire life,” she says. “Senator Sanders hasn’t achieved that, and I don’t believe he can for our country. So unless you can prove to me that someone on day one knows how to walk in and knows how to define the challenges in our society that need addressing — for real, not for fake, not for talk, not for like, ‘We’re going to drain government of money.’ ” She trails off. “Mike has done that.”

Like the party as a whole, Bloomberg is now trying to move himself to the left, even if at his core, he doesn’t really seem to believe in helping people who aren’t helping themselves. I once heard him say to a voter asking about Social Security and Medicare, “In this country, we can’t have somebody dying in the streets without being able to see a doctor. On the other hand, the taxpayer says, ‘Look, there’s a limited amount of money that I have.’ It’s balancing that …” The voter interrupted, “It’s called civilization, though,” to which he shot back, “You’ve got that one right.”

And even though he’d said he wouldn’t go after other candidates, when Sanders attacked him, he started to, calling Sanders a “communist” and putting out press releases about some people, possibly Sanders supporters, though who knew, defacing Bloomberg-campaign windows around the country with phrases like CORPORATE PIG and EAT THE RICH. When I talked to Sheekey, in mid-February, he said, “The contest really has turned because we have this existential threat. We have Bernie Sanders, who’s now without question the Democratic front-runner, and that’s true as you think forward, looking at the delegate count, or politically it’s true in any poll you would take nationally. But who ultimately would probably lose in the general election with Donald Trump.”

On February 20, the campaign got more aggressive about the field, with Sheekey publicly calling on Klobuchar, Buttigieg, and Biden to all vamoose out of the race. “That’s the most galling, hubristic bullshit I’ve ever seen,” says a Democratic strategist. “So you’re saying candidates who have spent a year earning support and votes and delegates should get out? Here’s another way of looking at it: If you weren’t diverting hours and hours of cable-TV coverage and print coverage, everyone in the middle might coalesce around Pete. You don’t have one pledged delegate yet, and we should all get out because you have money? That’s oligarchy. That’s madness.”

Plus at the end of February, Biden began climbing in the South Carolina polls. “One of the things even money can’t address is the unexpected consequences that happen in a multicandidate field — the physics of it,” says strategist Joe Trippi. “If Biden has a big win in South Carolina, it’ll be the Comeback Kid thing, and he’ll get three days of good TV coverage before Super Tuesday. That lifts him three or four points in some states.” Sanders might steamroll the field on Tuesday, or he might have to fight to the convention. At Bloomberg’s first debate, only the senator from Vermont said the party should accept the candidate with a plurality as its leader no matter what. If Sanders comes into the convention with 38 percent, Biden with 35, and Bloomberg is still hanging around with something decent, Bloomberg could throw the election to either of these guys. And we know it wouldn’t be Sanders.

If he’s not the nominee, Bloomberg has promised to keep field operations up in six battleground states, keep his digital operation up and running, and fund paid media with a focus on anti-Trump ads. But those promises might mean spending millions of dollars to elect a socialist whose campaign, when asked about the possibility of Bloomberg support last week, answered, “Hard no.” This makes Sanders seem a bit rigid — but Sanders’s supporters think Bloomberg himself is an ideologue motivated by his disdain of progressives. “He’s on a mission to stop Bernie or Warren,” says Waleed Shahid of Justice Democrats. “I would hope he would keep using his wealth to support democratic causes,” but “I’m a little concerned that he and Tom Steyer may have hurt feelings.”

Trippi feels confident Bloomberg will deliver. “I take his campaign at their word that they’re going to keep all these headquarters open and keep fighting,” he says. That did seem to be the conventional wisdom, both inside Bloomberg HQ and out; Bloomberg is not known to be petty, but someone who closely guards his legacy. But on February 27, in Houston, he said he’d shutter operations if the nominee rejected his support, as Sanders already had. “What do you mean, I’m going to send a check to somebody and they’re not going to cash the check?” said Bloomberg. “I think I wouldn’t bother to send the check.”

To those close to the campaign, this looked like a temporary squabble of the kind that comes up regularly in primary seasons only to disappear by the fall — not a real obstacle to Bloomberg spending Trump out of office, and maybe just a show for the cameras. But any purse-tightening would represent a colossal walk-back from Bloomberg, given how regularly and steadily he’d been proclaiming he was in this to beat Trump and would do anything it took no matter the nominee — promises that had earned him additional goodwill among the Establishment of the party he’d been funding so lavishly and would now be, hypothetically, disavowing. The campaign says nothing like that is likely to happen: “Mike has said he will happily support another Democrat if he’s not the nominee. It’s up to them whether they want the support or not.” If the candidate refuses, they say, Bloomberg would just spend the money on an anti-Trump super-PAC, as was always the plan (he would never have been able legally to donate more than $2,800 to the campaign itself). But even if the dustup settles quickly, it’s likely the psychodrama between these two egos will be playing out all summer and fall.

As the countdown clock read five days and 13 hours and three seconds before Super Tuesday, plus 250 days until the general election, Bloomberg came into the office to meet a smattering of mayors. The event was a curious one but in line with his desire to shake up campaigns: His team had put up a billboard in Times Square and asked people to call in with questions for Mike, then flown in these mayors to take the calls. They huddled with Bloomberg and their cell phones at several white desks (whether those on the other lines were so random as to be coaxed to call Bloomberg via a billboard I would not venture a guess). The first, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, formerly of Baltimore, had phone issues, but Bloomberg stood by patiently. “You should go to Silicon Valley. There’s no cell service,” he said. “Wait until they have a heart attack and nobody can call a doctor. There’s actually a couple golf clubs who are changing their rules for just that reason.”

When the phone bank is over, a half-dozen top staffers gather near the front door, some off with him to Massachusetts, Tennessee, Alabama, Texas, and elsewhere before Super Tuesday. The group rides an elevator down, but moments later Bloomberg appears with his security guard, who is urgently talking into an earpiece, trying to locate the inner circle that has just disappeared. Bloomberg’s sure the crew has gone downstairs and is probably already in a car waiting for him, but the security guard wants him to stay put. Now young staffers notice him and, surprised to find him unsurrounded, stop to shake his hand or ask how long he’ll be gone. “I didn’t know how much to pack, because I’m leaving for four days,” he says — he wasn’t sure about how many shirts, how much underwear. The tall mayor of Paterson, New Jersey, from the earlier phone bank, comes by, then asks me to take a picture of them together. Bloomberg’s security guy finally waves at him to get in the elevator as the mayor holds up his phone to show me the picture. It’s not a good shot. “My head’s cut off,” he says.

*This article appears in the March 2, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!