The kids are all left. Or, almost all Democratic voters under 30 are, anyway.

Blue America’s gaping chasm of a generation gap has been a — if not the — defining feature of the Democratic primary race thus far. An Economist/YouGov poll released this week found that 60 percent of Democrats younger than 30 support either Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren; among those 65 and older, the progressive candidates’ combined total was 27 percent. Before the Vermont senator’s strong showings in Iowa and New Hampshire, surveys showed an even wider age divide: In late January, Quinnipiac had Joe Biden leading the field nationally — even as he trailed Bernie Sanders among voters 35 and younger by a margin of 53 to 3 percent. Exit polls from New Hampshire affirmed this generational split, with Sanders winning 47 percent of voters 18 to 29, but just 15 percent of those over 65.

That young people are clamoring for radical left-wing reform in such exceptional numbers would be noteworthy enough, were it confined to the United States. But the phenomenon is apparent throughout the Anglophone world. Millennial leftists lifted Jeremy Corbyn to the leadership of Britain’s Labour party, and their peers would have put him in 10 Downing Street if they’d had their druthers: Exit polls of the 2019 British election found Corbyn’s party winning voters under 30 by roughly 55 percent, even as it claimed just 14 percent of those over 70. And just this week, young Irish voters propelled their nation’s leftwing party, Sinn Féin, to a surprise popular vote victory in Ireland’s parliamentary elections.

So: What’s the matter with kids these days?

America’s glibbest pundits have attributed Sanders’s youth support to the perennial idealist naïveté of the post-adolescent. But it isn’t actually the case that young voters have forever and always been left wing. In exit polls of the 1984 election, Ronald Reagan won voters under 25 by a margin of 61 to 39 percent. Developmental psychology can’t tell us why so many of Pete Buttigieg’s peers pine for class war.

Others attribute millennials’ aberrant fondness for socialism to the Soviet Union’s disappearance into the dustbin of history: Americans who were either unborn or barely sentient during the Cold War’s denouement were bound to find egalitarian economic ideas more appealing than their forebears, many of whom spent their formative years cowering beneath their classroom desks in anticipation of nuclear annihilation at the hands of the reds. And this is surely part of the story. But even if the Cold War’s end was a necessary condition for youth leftism, it was scarcely a sufficient one. After all, the first post-Soviet decade witnessed the opposite of socialist revival across the Western world, as center-left parties moved right and stock markets shot up.

For this reason, most competent commentators give the Great Recession a starring role in their narratives about the Sanders phenomenon. Their story is straightforward: Americans under 35 saw capitalism discredit itself in world-historic fashion while their worldviews were still taking shape. They proceeded to watch a putatively liberal government bail out the very financial institutions whose malfeasance had birthed the crisis, and then preside over a historically weak recovery that left many a millennial college graduate debt-burdened and underemployed. This created a burgeoning market for market-skeptical critiques of Democratic politics as usual — and progressives and socialists ably served it.

I think this narrative is largely right but incomplete. The 2008 crash was central to the radicalization of the millennial and Gen-Z cohorts, but the broader economic system that both enabled and survived that crash is also implicated. Vox’s Matthew Yglesias is among those who’ve entertained the opposite view. During an interview with economist Karl Smith last year, Yglesias suggested that American policymakers may have accidentally engineered a Marxist revival in the wake of the Great Recession by refusing to supply the economy with the scale of fiscal and monetary stimulus necessary for promptly restoring full employment. And Yglesias is doubtlessly correct that Congress’ superstitious fear of deficits — and the Federal Reserve’s paranoia about inflation — conspired to needlessly prolong mass unemployment and wage stagnation during the post-2008 recovery. It seems likely that this policy failure expanded the audience for radical critiques of the existing order. But the tentative conclusion that Yglesias draws from these premises — that a swift return to full employment would have rendered millennial and zoomer leftism a marginal phenomenon — is (probably) wrong.

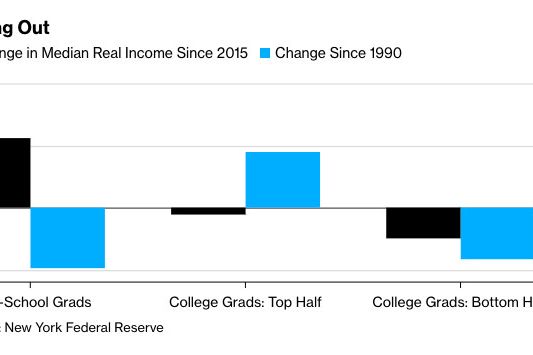

To see why, consider three remarkable data points from this column by Bloomberg’s Alexandra Tanzi and Katia Dmitrieva: (1) The unemployment rate among recent college graduates in the U.S. is now higher than our country’s overall unemployment rate for the first time in over two decades, (2) More than 40 percent of recent college graduates are working jobs that do not traditionally require a bachelor’s degree (while one in eight are stuck in posts that pay $25,000 or less), and (3) the median income among the bottom half of college graduates is roughly 10 percent lower than it was three decades ago.

That last point is illustrated in this exceptionally revealing chart:

Thanks to a combination of the Obama era’s slow but steady wage and employment gains — and the Trump presidency’s bonanza of deficit spending and loose money — America has returned to something resembling full employment. The percentage of Americans who are looking for a job but can’t find one is now near half-century lows. And yet, the “full employment economy” that awaits this year’s graduating class looks quite different than the one that welcomed their Gen-X and boomer predecessors. In earlier boom-times, the labor market evinced an insatiable demand for white-collar workers. Today’s, by contrast, has more aspiring professionals than it knows what to do with. And the same can be said of the economy that greeted matriculating Corbynites in the U.K.

Put differently: Even as the price of a college diploma has risen nigh-exponentially (thereby forcing the rising generation of college graduates to saddle themselves with onerous debts), the value of such diplomas on the U.S. job market has rapidly depreciated. And there is little reason to believe that this state of affairs will change, no matter how long the present boom is sustained. According to the Labor Department’s estimates, the five fastest-growing occupations in the United States over the next ten years will be solar-panel installers, wind-turbine technicians, home health aides, personal care aides, and occupational therapy assistants. Not a single one of those jobs requires a four-year college diploma. Only occupational therapy assistants need an associate’s degree.

Throughout my (1990s) childhood and adolescence, leaders in both major parties heralded the arrival of a “knowledge economy,” and attributed rising income inequality to a “skills gap.” Our economic system was still capable of providing a broad middle class with high-wage, high-quality jobs; it just needed more Americans to accrue the levels of skill and education that the jobs of tomorrow required. There was an endless supply of cushy, professional-class posts awaiting those who answered our economy’s demand for highly educated workers. Economic security would come to those who did their homework.

But this story has proven to be little more than a self-flattering delusion of our (highly educated) political class. Our economy only needs so many lawyers, consultants, and financial analysts (let alone, journalists). Nor, as presently structured, can it sustain an ever-growing caste of well-remunerated coders. We have a lot of elderly people who need help going to the bathroom, and a lot of manual labor that our robots aren’t dexterous enough to perform. Most of the work that our society truly needs to get done every day doesn’t require elite academic or intellectual capacities. And thanks to the collapse of the American labor movement, most that blue and pink-collar work pays terribly. The two occupations poised to add the most jobs to our economy over the next ten years — home and personal care aides — pay an average salary of about $24,000 a year.

A vulgar Marxist looking at Bloomberg’s chart might predict that the college students and graduates of less prestigious, public universities — who have been most disserved by the “knowledge economy” myth — would be even more inclined toward left-wing politics than their Ivy League peers. And the results of the New Hampshire primary lend credence to that view: While Pete Buttigieg held his own in the town of Hanover, home to Dartmouth, Sanders cleaned his clock in the precincts surrounding the University of New Hampshire.

To be sure, college graduates still account for a minority of Americans under 35. But whereas this white-collar subsection of previous rising generations was predisposed to view the market economy more favorably than their less educated peers, millennial matriculators largely don’t. In fact, the overeducated, precariously employed college graduate is the modal millennial socialist.

Which makes sense: Tell a subset of your population that they are entitled to economic security if they play by certain rules, provide them with four years of training in critical thinking and access to a world-class library — then deny them the opportunities they were promised, while affixing an anchor of debt around their necks — and you’ve got a recipe for a revolutionary vanguard.