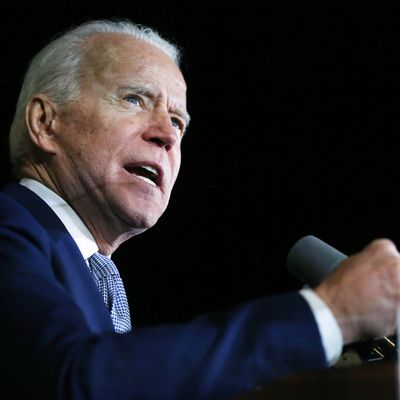

A few days ago, the Democratic Party Establishment was in a panic. Bernie Sanders was poised to sweep aside a divided field of opponents and amass an insurmountable delegate lead on Super Tuesday. Instead, Joe Biden has come away with more of the delegates, combining overwhelming victories in southern states with surprise upsets in Massachusetts and Minnesota. Below are five takeaways on what that means going forward.

1. The race reverts to normal

Viewed from the perspective of the last few weeks, the race has been a wild swing, with Biden skyrocketing out of nowhere and Sanders dropping like a stone. Viewed from a longer-term perspective, we’re just back to where things stood for most of the race.

Joe Biden held a steady national lead, which he failed to surrender despite several shaky debate performances and weak fundraising. He only lost his national lead after his miserable performance in the Iowa caucus. That was mainly a fluke of timing. Iowa is heavily white. Caucuses draw a fraction of the turnout of a primary, consisting mainly of the most committed voters. If Iowa was decided by a primary rather than a caucus, Biden probably would have won, despite the demographics. (He won neighboring Minnesota without spending a cent there.)

His Iowa failure led to another failure in New Hampshire, another nearly all-white state, causing many of us to leave him for dead. But had the states voted in another order — almost any other order — Biden probably wouldn’t have lost his national lead in the first place. The surge he enjoyed over the last few days may have reflected nothing more than Biden winning a race and proving he was viable to people who had wanted to vote for him all along.

If this is true, Biden is in a commanding position. Sanders only held his head above water because several states had early voting before Biden consolidated the center-left. The delegate count is artificially close, representing, in part, a time-capsule glimpse of the period when he enjoyed a divided opposition.

2. Bernie’s strategy is not enough

Last April, Sanders aides explained to Edward-Isaac Dovere that they expected the African-American vote to be split between their opponents, allowing Sanders to rely on wins in white states like Iowa and New Hampshire, then squeeze out a victory with no more than a third of the delegates. (“They say they don’t need him to get more than 30 percent to make that happen,” he reported.)

For the most part, Sanders has hewed to that strategy. He has run a largely factional campaign, making slashing attacks on the party Establishment. He has not won enough votes from moderate and moderately liberal Democrats.

And since Bernie’s pitch never, ever changes — he rotates between the same handful of riffs he has used for years — it’s hard to think of what he could do to enlarge his coalition, or if he even wants to.

3. The Sanders electability pitch is also failing

When asked how he can beat Trump, Sanders has one answer: He will inspire the biggest voter turnout in American history by energizing young people. He is certainly winning young people by enormous margins. But he is not turning them out in anything like the kind of historic numbers that would be needed to build a majority.

4. Biden will run on the economy, too

The former vice-president has emphasized character and restoring decency. (This theme did not help Hillary Clinton win in 2016, but it did help George W. Bush win in 2000, in the face of a healthy economy.) Biden failed to mention the economy at all in his Monday night rally, where he accepted endorsements from Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, raising fears he plans to campaign in the fall entirely on this basis. But his Super Tuesday speech had plenty of economic policy meat, citing expanded health care, climate change, and other standard Democratic domestic reforms.

5. This wasn’t a total loss for the left

The last few days probably feel crushing to the party’s left wing, with Sanders surrendering his lead and Elizabeth Warren failing to win delegates almost anywhere while finishing third in her own state.

But the left played an important role in the process by registering its intense opposition to Michael Bloomberg. A few weeks ago, Bloomberg was collecting endorsements and seemed poised to build the Establishment consolidation that is now behind Biden. Bloomberg’s disastrous debate performance clearly helped bring about his demise. But the left’s intense objection to Bloomberg, and his long record of personal and ideological offenses, communicated an important message: Bloomberg was a bridge too far.

Of course, the left has complained about Biden too. For that matter, it has complained about everybody who wasn’t Bernie. But the Bloomberg complaints were broader and deeper, and probably convinced the party Establishment that Bloomberg was not going to allow them to consolidate the party, ultimately leading them to revert to Biden. If, say, James Clyburn decided Bloomberg was his strongest bet, he would have let Biden dangle rather than endorse him.

Having influence in a party is not always about getting your top-ranked choice. Sometimes it means vetoing your bottom-ranked choice. (The old Dixiecrat wing historically exercised plenty of these sorts of vetoes, flexing muscle even without getting its top preference.)

Sanders’s candidacy is in real trouble, and needs a dramatic reversal to change a dynamic in which Biden probably leads nationally by double digits. There aren’t many more pre-South Carolina time-capsule votes to save Sanders now. If he’s going to overturn Biden’s lead again, something needs to change.