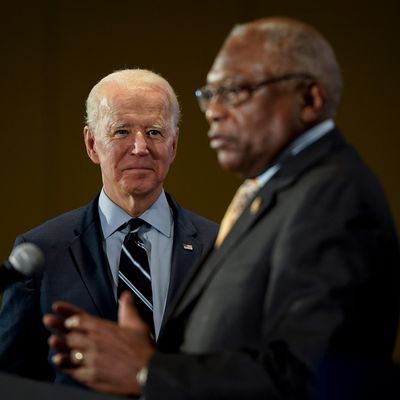

There’s a general consensus that a lot of Joe Biden’s success on Super Tuesday is attributable to James Clyburn, the House Majority Whip from South Carolina. A U.S. representative since 1993 and the highest-ranking black official in Congress, Clyburn is regarded as something of a kingmaker whose endorsement is one of the Democratic primary season’s most coveted. The weekend before Saturday’s Palmetto State contest saw a surge of momentum favoring Bernie Sanders; the Vermont senator was fresh off a decisive victory in the Nevada primary and seemed poised to cement his dominance when California, Texas, and 12 other states voted the following week. He trailed Biden in the polls in South Carolina but the margins were narrowing, and his front-runner status seemed all but assured. Then Clyburn endorsed Biden and the former vice-president won big in South Carolina. Biden’s victory was so commanding that it prompted three of the seven remaining candidates to drop out, two of whom swiftly endorsed him, and drove a dramatic and unprecedented realignment of voters behind his campaign just in time for Tuesday’s elections.

It was a storybook turnaround, and Establishment Democrats seemed to be thrilled by the result. “That guy literally saved the Democratic Party,” longtime operative James Carville remarked of Clyburn. “You brought me back,” Biden told Clyburn this weekend, thanking him for his cosign. The South Carolina congressman’s cachet is hard to dispute: According to USA Today, citing exit polls, 47 percent of South Carolina Democratic primary voters said that Clyburn’s endorsement was an important factor in their decision to support Biden; 24 percent said it was the most important factor. For the congressman, his blessing was merely a well-timed public manifestation of a decision he’d long ago made in private. “I’ve known for a long time who I was going to vote for,” Clyburn told USA Today.

But now that Clyburn has made his choice and much of South Carolina’s electorate — and those in most of the Super Tuesday states — has followed suit, the congressman is, in his own words, tasked with “[protecting his] investment.” “I’ll go wherever he ask [sic] me to go, with him or without him,” Clyburn has said of the former vice-president. That’s meant making the media rounds to share his thoughts about how Biden’s campaign might improve and generally make the case for electing a man who is 77 years old and seems to increasingly have trouble forming coherent sentences. Such an effort prompted the following remarks from Clyburn on MSNBC on Tuesday:

I … thought that [Biden] needed to have speechmaking — more feeling than just laying out policy. Joe Biden has a tremendous record. He has a tremendous history. He’s just a good guy. And I said when I made my endorsement: “I know Joe. We know Joe. But most importantly, Joe knows us.”

To summarize, Clyburn is arguing that Biden’s public addresses need to be more emotionally rousing than policy focused. This may be sound advice in an election where galvanizing voters to beat Sanders, a noted firebrand, and eventually Trump, a voluble egotist who lavishes himself with rallies as a kind of periodic treat, will be at a premium. But it’s also rarely been Biden’s problem.

On the contrary, an excess of feeling is the lifeblood of his campaign. His policies, such as they are, are milquetoast appeals to moderation in the face of impending catastrophe — vows to compromise on legislation with Republicans, despite their demonstrated commitment to steamrolling democracy in the interest of partisan advantage; refusals to fight for free health care for all in the name of preserving private insurance, despite the rampant horror stories of insulin rationing and deferred emergency-room visits that prevail among the tens of millions of uninsured or underinsured Americans.

But where his policies underwhelm — and, indeed, most voters would be hard-pressed to name a single one — his campaign has found incredible success drawing on voters’ emotional attachment to what they think he represents: a return to the sociopolitical norms that were so rudely disrupted by Trump’s election. “We’re in a battle for the soul of America,” Biden’s campaign site reads. The idea is that Trump took something away from us — an ill-defined feeling that we’re not actually the America that he suggests we are. Biden is offering nothing more ambitious than returning things to the way they used to be.

This pitch has trouble withstanding scrutiny. The norms to which Biden hopes to return us are perhaps best encapsulated by his own recent promise to billionaire donors that “no one’s standard of living would change” should he win the White House. It’s a vivid illustration of one of Trump’s most notable accomplishments: convincing large swathes of the public that a system which produced historic levels of wealth inequality, financial crises on a scale not seen in decades, a rapidly unfolding climate cataclysm, and the globe’s highest incarceration rate doesn’t need a dramatic overhaul — simply a person in the driver’s seat who isn’t him. But more relevant to the immediate requirements of running a campaign and winning an election, the feeling of reassurance derived from familiarity that Biden generates is at odds with his own conduct. He’s flailed in debates, losing track of his own thoughts mid-sentence and cutting himself off prematurely when he realizes his argument is going nowhere. His tendency to ramble and wax poetic about the old days has caused him to speak fondly of working cordially with segregationists.

Voters have nonetheless found comfort in Biden’s promises to make things normal and familiar again. But despite Clyburn’s insistence that “we know Joe,” this isn’t the Biden we’ve come to know. The man who eviscerated Paul Ryan in the 2012 vice-presidential debate is gone. The senescent shell of that man, who’ll take the debate stage in Arizona next week, is America’s savior only by the most acrobatic stretches of the Democrat imagination. But Clyburn is right that leaning into feeling is Biden’s best bet. The former vice-president’s lackluster fundraising has meant he was unable to spend much on ads or establish campaign field offices in Alabama, Arkansas, Maine, Minnesota, Oklahoma, or Tennessee. He won them on Super Tuesday anyway. It’s hard to explain this by means other than voters imagining a Biden who no longer exists. This isn’t unheard of in an election, but it’s especially risky here given its distance from reality.