In 1993, the peak year for firearm violence in U.S. history, guns killed nearly 40,000 Americans. In 1995, the deadliest year of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, 43,000 Americans lost their lives to the virus. In 1972, the heyday of the Ford Pinto and nadir of automotive safety in the country, 55,000 died in car accidents. The entire Vietnam War claimed 58,000 American lives.

Last year, drug overdoses killed 70,980 Americans, narrowly beating 2017’s record-setting death toll, according to preliminary data from the CDC.

The new figures shatter the fragile hope offered by 2018’s 4.6 percent decline in fatal overdoses, which marked the first annual reduction in such deaths in 28 years. What’s more, like so many of our nation’s other endemic pathologies, the overdose epidemic appears to have grown even more severe in 2020 than it was one year ago.

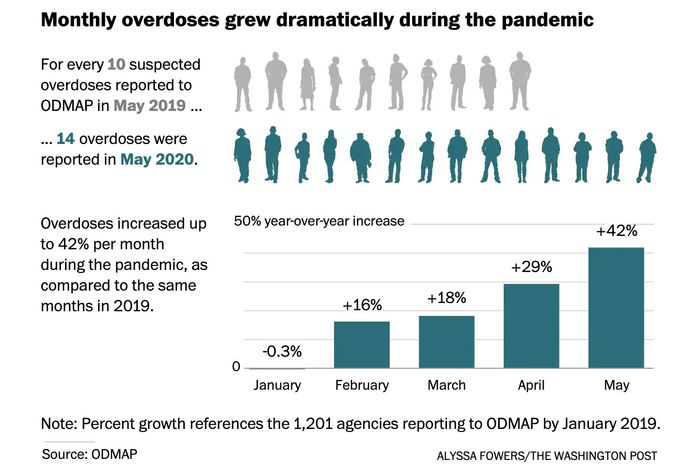

The number of suspected overdoses in the U.S. — both fatal and nonfatal — was 18 percent higher this March than it was the same month last year, according to the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program. In April, overdoses were up 29 percent; in May, 42 percent.

In some respects, it is intuitive that the present crisis would trigger an uptick in overdoses. Unemployment and social isolation are both risk factors for addiction. And tens of millions of Americans were thrown out of work and/or isolated at home over the past four months. Such isolation not only increases many addicts propensity to use, but also reduces the likelihood that a friend or loved one will be around to provide treatment or get help. As the Washington Post illustrated using data from the Cook County Medical Examiner’s office, a surge in probable overdose deaths followed the state’s stay-at-home order.

That said, some had hoped that the pandemic might mitigate the opioid crisis by disrupting the global narcotics industry’s supply chains. But such optimism was misplaced. Overdoses are often a byproduct of the information asymmetry between buyers and sellers in illicit markets. If a user buys something she believes to be heroin, but is actually fentanyl, then her usual dose becomes a fatal one. Similarly, with their traditional suppliers and substances disrupted, users are turning to less familiar and often homemade drugs, and this appears to be fueling widespread dosing errors.

The calamity is being further exacerbated by widespread closures of treatment centers and recovery programs. For now, the scaling back of these services is primarily driven by the exigencies of shutdown orders and social-distancing protocols. But a great many of these facilities may soon shutter permanently, as a result of financial insolvency. Of the 3,326 treatment organizations that are part of the National Council for Behavioral Health, 44 percent say they are poised to run out of money within six months.

In May, the Trump administration cited the importance of averting overdoses as a reason for states to rapidly reopen their economies. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post titled “We must reopen – for our health,” in which he noted, “each one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate translates” to “a more than 3 percent increase in opioid deaths.”

This argument fails on its own terms for reasons that are now clear. Shutdowns weren’t the root cause of mass unemployment, the coronavirus was. Thus, hasty reopenings did more to increase unemployment in the long run than to reduce it.

But the administration’s position appears less ill-conceived than disingenuous. Even as the White House was imploring the nation to consider the plight of addicts, it refused to endorse a bill passed by House Democrats that would invest $3 billion into mental health and drug treatment programs. As is, just $425 million of the $2.5 trillion in coronavirus relief funds went to such facilities, even as these thin-margin operations have seen their revenues collapse.

It’s quite possible that there has never been a worse time to allow substance-abuse programs and mental health service providers to fail en masse. This April, the federal emergency mental health line saw a 1,000 percent increase in text messages from the year before. In a recent survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation, more than half of U.S. adults said that the pandemic had impaired their mental health. Meanwhile, as The Atlantic has noted, there is reason to fear that many of the millions of Americans who survive COVID-19 will go on to suffer from psychological ailments:

The SARS pandemic tore through Hong Kong like a summer thunderstorm. It arrived abruptly, hit hard, and then was gone. Just three months separated the first infection, in March 2003, from the last, in June.

But the suffering did not end when the case count hit zero. Over the next four years, scientists at the Chinese University of Hong Kong discovered something worrisome. More than 40 percent of SARS survivors had an active psychiatric illness, most commonly PTSD or depression.

Grave on their own, all of these maladies are also risk factors for substance abuse.

Last year, when unemployment was near half-century lows, Americans lost an unprecedented number of loved ones to drug overdoses. This year, they will almost certainly lose more. And if Congress does not fully fund science-based, harm-reduction strategies for minimizing overdoses, we are liable to continue seeing mass death — even after we reach the “post” phase of this pandemic’s traumatic stress.