The GOP’s ideology has long been a threat to the powerless. The party’s opposition to social welfare immiserates the poor, its nativist demagoguery endangers immigrants, and its contempt for climate science could exhaust the earth’s hospitality by the time America’s disenfranchised children come of age.

But as the COVID-19 crisis wears on, it has become apparent that Republican ideology also threatens the power of Republican ideologues themselves.

Mitch McConnell’s Senate caucus has had four months to prepare for the possibility that the U.S. economy would not be strong enough in late July to withstand the sudden cessation of enhanced unemployment benefits. It has had two months to prepare an answer to House Democrats’ blueprint for the next coronavirus relief package. Instead, it botched its attempt to unveil such a bill this week and now appears unlikely to pass a new one before 30 million unemployed Americans see their weekly incomes suddenly crater.

When it passed the CARES Act in March, the congressional GOP insisted on having the bill’s $600-a-week unemployment-benefit bonus phase out at the end of July. Since then, the party has refused to approve any additional fiscal aid to states, households, or other needy constituencies on the grounds that a V-shaped recovery might soon obviate the need for further federal largesse.

If it wasn’t clear in March that the U.S. was in for a prolonged period of high unemployment, it has been since mid-June, when new COVID cases began climbing across the Sun Belt. But even if we postulate that it was reasonable for the GOP to wait until the last possible minute before extending benefits, there would be no excuse for the party’s failure to have a relief bill ready to go just in case. Even the most bullish economic forecasters didn’t rule out the persistence of double-digit unemployment this August as a significant possibility. So why then did McConnell wait until federal unemployment benefits were about to expire to start crafting another stimulus package? And why did Republicans fail to rally behind his outline this week, forcing the majority leader to abandon the bill’s rollout on Thursday morning?

The answer to both questions appears to be this: Many congressional Republicans earnestly believe that the reason unemployment is high — in the middle of an uncontained pandemic that is killing 1,000 Americans a day — is that the excessive generosity of federal benefits has rendered the unemployed unwilling to work.

McConnell’s procrastination has been widely interpreted as a means of gaining leverage over House Democrats: Since the Donkey Party cares more about the unemployed than the GOP, best to conduct negotiations while the calendar is slowly lowering the jobless into a pit of molten lava. And this may have been part of the intention. But the majority leader doesn’t just need leverage over Nancy Pelosi to get his preferred bill enacted; he also needs leverage over his own party’s anti-spending fanatics. Given McConnell’s failure to rally Republicans behind a package this week, it seems quite likely that his procrastination was born partly out of the hope that proximity to a fiscal cliff might chasten his caucus’s anti-Keynesian true believers.

Alas, they remain unchastened. As Bloomberg reported Friday morning:

[Wisconsin senator Ron] Johnson said he simply doesn’t want to spend any more money and plans to oppose the bill he hasn’t seen. Senator Ted Cruz of Texas told CNN he’s a “hell no” on a $1 trillion package, while Rand Paul of Kentucky told another reporter that Republicans were acting like “Bernie Bros” behind closed doors as they discuss among themselves how many hundreds of billions to spend, a reference to ardent supporters of Senator Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist.

“Let’s allow the monthly incomes of 30 million unemployed people to collapse — even as much of the economy remains inoperable — just months before Election Day” appears to be a minority position among congressional Republicans. McConnell could easily find the votes for a relief package of some kind without appeasing Paul, Johnson, and Cruz. Doing so would require securing Democratic buy-in, of course, but that will be a necessity regardless; the legislative filibuster still exists, and Democrats control the other branch of Congress. Nevertheless, McConnell would ostensibly prefer to allow federal unemployment benefits to temporarily expire than to enter negotiations with Democrats without a consensus GOP plan in tow. Thus he must find a way to talk sense into conservative hard-liners.

That’s easier said than done. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed Thursday, Johnson elaborated on the hard-liners’ case for doing nothing. Here’s the core of it:

Recent economic forecasts have predicted a decline in gross domestic product of between 4.6% and 8% for 2020. The damage from Covid-19 has been significant, but not catastrophic.

Congress authorized $2.9 trillion of Covid-19 relief, which represents 13.5% of 2019’s U.S. GDP. No one knows exactly how much of the Covid relief has been spent or obligated, but 60% ($1.75 trillion) seems to be a consensus figure in Congress. Let that sink in. We’ve authorized enough spending to replace 13.5% of annual economic output, and more than $1 trillion of it hasn’t yet been spent or obligated. So why is Congress rushing to pass at least $1 trillion more?

To this point about GDP, Johnson adds the argument that COVID-19 is not much more deadly than the flu, and thus, “there is no need to continue broad economic shutdowns with fatality rates in these ranges.”

This last point is the most patently mad. Johnson derives his dovish estimate of the virus’s death rate from a JAMA study suggesting that asymptomatic coronavirus infections may be an order of magnitude more prevalent than previously understood. If we pretend this is a proven fact, then it would indeed mean the coronavirus is less lethal than previously assumed — but also that it is even more contagious than we’d realized. A virus that is just a bit deadlier than the flu but exponentially more infectious would be a much bigger public-health problem than influenza! We know COVID-19 is capable of killing 140,000 Americans in the space of four months. The fact that hundreds of thousands of Americans may have been infected with coronavirus without realizing it does not render those 140,000 people less dead. So assuming that we all value the lives of senior citizens, it is not clear why Johnson believes the average individual rate of survival from coronavirus infection is a sound metric for determining whether economic shutdowns are justified.

Regardless, the notion that the present economic crisis is rooted in overly restrictive coronavirus-containment measures is itself wildly delusional. In April, Johnson’s reasoning was reckless; today, it’s hallucinatory. We already ran the senator’s desired experiment! Texas, Louisiana, and Arizona reopened. Their economies rebounded for a few weeks, then COVID-19 cases surged, consumer demand fell, businesses started failing, and state governments were eventually forced to stall or reverse their reopenings to preserve hospital capacity. Texas’s economy isn’t suffering because its (Republican) political leadership overreacted to an overhyped flulike virus. It is suffering because that leadership cannot force consumers to shop or eat out when a potentially fatal infectious disease is running rampant in their communities, nor persuade voters that allowing the infected to overrun hospitals is an acceptable price for sustaining business as usual.

Johnson’s belief that “We have nothing to fear but fear (of a virus that has already killed 147,000 Americans) itself” is a winning argument testifies to both the power of motivated reasoning and the strong incentives that ideologically committed conservatives have for denying the reality of a crisis that admits no “small government” solution.

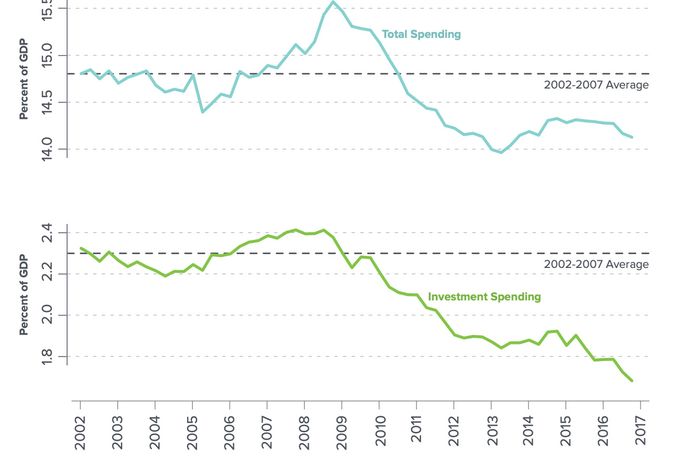

Republicans have long veiled the suffering of low-income Americans behind GDP data, but Johnson’s attempt to build a case for complacency out of macroeconomic statistics is especially strained in the present context. Whatever COVID-19’s ultimate impact on GDP, tens of millions of Americans will see their take-home pay fall next week if Congress does not extend existing benefits. This much we know. We also know that, absent federal aid to states and cities, public-sector job losses will accelerate in the coming months, a development that will not only increase unemployment among government workers but also sap demand for private-sector businesses. Cuts to state-level public investment will further erode economic demand at a time when private firms are cutting capital expenditure. Furthermore, withholding fiscal aid from states may also undermine public-health efforts to contain the virus. There is some evidence that U.S. states have opened prematurely out of a desperate desire to restore sales and income-tax revenues to compensate for a dearth of federal support. All of this will deepen the recession and weaken the recovery. In fact, one of the primary reasons why the post-2008 recovery was so slow and weak was that states and cities were laying off workers and canceling investment projects for the bulk of it. As the Roosevelt Institute’s Mike Konczal and J.W. Mason have illustrated:

The CARES Act provided states and cities with $0 in unconditional fiscal aid. A wide variety of business leaders have advised Congress that $1 trillion in such aid is needed to keep the economy afloat. Meanwhile, more than 20 million Americans are poised to be thrown out of their homes by late fall, when a moratorium on evictions in federally subsidized buildings will expire.

Even if that moratorium is extended, millions of tenants will have accumulated thousands of dollars in back rent that they have no means to repay.

And Ron Johnson doesn’t understand why Congress is “rushing to pass” more relief spending.

Such willful blindness to economic empiricism and the plight of nonaffluent Americans would be unremarkable with a Democrat in the White House or Election Day further in the future. During the Obama years, the GOP made its willingness to put partisan advantage above the general welfare perfectly clear. In ushering a historically unpopular tax-cut package through Congress in 2017, the party demonstrated its faith in the amnesia (and/or indifference to policy details) of the median voter.

But Johnson, Cruz, and Paul are imploring their party to chart an economic course that leads straight to electoral ruin. All historical precedent indicates that voters will hold the president’s party responsible for economic conditions. If Republicans do as Johnson advises and allow the typical unemployed American to see her monthly income fall by $2,400, while states and cities lay off public workers en masse and landlords kick millions of families to the curb — during the home stretch of a general-election campaign — then Democrats will almost certainly secure full control of the government next January. Which is to say, dogmatic adherence to conservative orthodoxy is not even in the best interest of the conservative ideological project. If your primary concern is curtailing progressive redistribution, preventing the Democratic Party from taking power in the midst of a historic economic crisis should be a top priority. But a critical mass of congressional Republicans missed the memo differentiating what the conservative movement actually believes (that economic policy should be directed toward maximizing plutocratic prerogatives) from what it pretends to believe (that countercyclical spending doesn’t work). And so McConnell must reason with colleagues who genuinely think the party can revive the economy by removing all fiscal life support.

The consequences of this madness will be most dire for America’s least enfranchised. But the harms wrought by the conservative movement’s ideological delusions will be felt by virtually all Americans — including the movement’s own congressional dogmatists.