In 1997, Al Gore was engulfed in what was considered at the time to be a massive scandal: He had almost, though not quite, violated the Hatch Act, a 1939 law prohibiting federal employees and property from being used for political purposes, by making fundraising calls from his White House office. The contemporaneous coverage of this event reads like a dispatch from another planet.

Gore “used legalistic language, which he repeated verbatim several times, to say he had not violated another law that prohibits anybody from raising campaign money in the White House,” reported the New York Times. While conceding Gore had probably not violated the letter of the law, and also not violated the spirit, which was intended to prevent officials from shaking down applicants for kickbacks, the Times explained, “The scrutiny of the Democrats has turned both on the legality of some of the donations they received and on the seemliness of Mr. Clinton’s use of his incumbency to raise money.” The scandal was deemed serious enough that, three years later, the phrase “no controlling legal authority” appeared routinely in campaign reports as a synecdoche for Gore’s scandal-tarred image, sort of a precursor for “Clinton emails.”

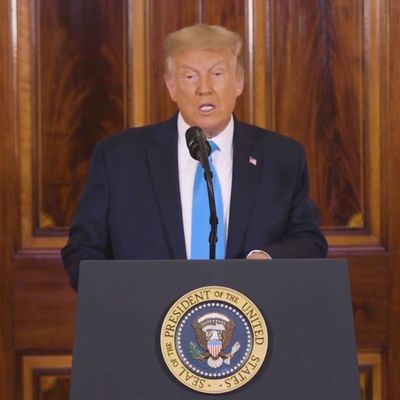

Someone who fell asleep 20 years ago and awoke last night would have been in for a shock. The second night of the Republican convention was a festival of massive lawbreaking. In open violation of the Hatch Act, President Trump turned the White House into a convention stage. He even held an immigration ceremony on camera, and had his secretary of State deliver a speech in explicit violation of State Department regulations. The White House might as well have been surrounded by yellow police tape. Had Al Gore tried it in 2000, he might have spent the night in jail.

Instead, the blatant violation was met with resignation. “Nobody outside of the Beltway really cares,” sneers Chief of Staff Mark Meadows. There is a controlling legal authority — they just don’t care.

Does the Hatch Act matter? Everybody in government thought it did, at least a little, right until the Trump administration. Government officials used to take pains to avoid using their offices for campaign purposes. Two former officials wrote about the hassle they would go through to avoid a small breach. The purpose of this restriction is clear enough: Control of the federal government is not supposed to grant the in party advantages (or at least not excessive advantages) over the opposition. Joe Biden can’t hold campaign events in the East Wing, so why can Trump?

The Trump administration has effectively turned the law into a dead letter, in following its basic principle that any law that lacks an effective and immediate enforcement mechanism essentially does not exist. Trump has ignored the law for years, using his official events for campaigning, while previous presidents carefully avoided doing so, and even reimbursed the government for expenses incurred while traveling for campaign events. After the Office of Special Counsel recommended firing Kellyanne Conway for Hatch Act violations last year, nothing happened. “Some of Mr. Trump’s aides privately scoff at the Hatch Act and say they take pride in violating its regulations,” reported the New York Times last week.

On the other hand, it’s true that the Hatch Act doesn’t matter that much. But it didn’t matter that much when Gore almost, but not quite, violated it. And for that matter, Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server, while a bad idea, didn’t matter that much either. The only bad outcomes of her disregard for federal email regulations was a massive array of news coverage depicting her as a scofflaw.

If Clinton had to do it all over again, she would no doubt make sure to follow the official email guidelines. Likewise, Gore would have walked across the street to make his fundraising calls. But would Trump change his convention events from last night? Almost certainly not. Whatever scolding coverage he’s attracted is a footnote.

Laws like the Hatch Act and prohibitions on using private emails for official purposes are in a category of laws that effectively bind one party but not the other. (Indeed, Trump’s administration is filled with private email users — nobody cares.) Why is that?

One reason, particular to this administration, is that Trump violates so many norms so flagrantly that he shatters the scale. There’s only so much journalistic bandwidth. Covering Trump’s violations of laws and norms by the standard you would apply to a normal president would mean banner headlines every day and interrupting television programming with breaking news every night.

But another, more long-standing, reason is that the two parties operate in structurally different news environments. The Republican base largely follows partisan Republican news sources, like Fox News, which largely do not hold their officials accountable. Republicans don’t have to worry that their small legal violations will make their own voters raise questions, because their own voters either won’t hear about the story in the first place, or — if it becomes too big to ignore — will learn about it in the context of some kind of whatboutist defense emphasizing how the Democrats are worse.

Democrats, on the other hand, have to communicate to their base through mainstream news outlets that follow traditional norms of journalistic independence. Of course you can critique the media for its implicit liberal biases. Even conceding for the sake of argument that the mainstream media has a strong social liberal bias, though, it is evidently true that they take Democratic violations seriously. The Times might go easy on any number of liberal shibboleths, but it was extremely tough on Clinton email protocol.

The media asymmetry is compounded by a structural bias in political representation. The House, Senate, and Electoral College all have Republican biases to various degrees. Republicans have the luxury of winning through pure polarized base appeals that Democrats do not enjoy. (This is one reason why, if you want Republicans to moderate, reforming the Senate would be a good start.)

And then there’s the additional problem that arises when reporters treat these asymmetrical conditions as unalterable and unremarkable features of the political landscape. From that standpoint, it’s obvious that minor Republican legal violations will not matter, and minor Democratic violations will. “Of course, much of this is improper, and, according to most every straight-faced expert, it’s a violation of the Hatch Act…” concedes Politico’s Playbook. “But do you think a single person outside the Beltway gives a hoot about the president politicking from the White House or using the federal government to his political advantage? Do you think any persuadable voter even notices?”

As analysis and prediction, this is correct. But it also has a self-fulfilling quality. Reporters assume small Democratic scandals “matter” much more than small Republican scandals, because Democratic voters follow news coverage that treats those violations seriously and Republican voters don’t. This is how you get to a world where Al Gore’s fundraising calls are still raising questions about his ethics three years later, while Trump’s latest obliteration of a law will be forgotten within days.