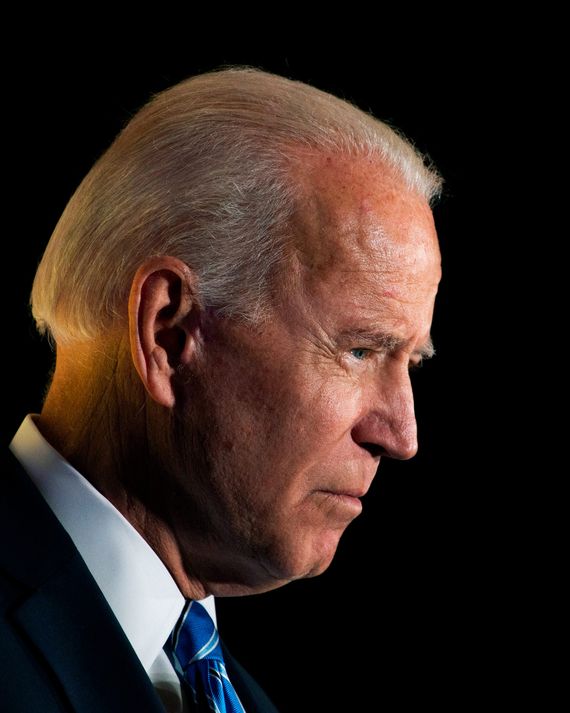

Since the pandemic shut down the country this spring, Joe Biden has repeatedly invoked a vision for his presidency as a New Deal–size national rejuvenation project, with himself playing the unlikely role of FDR. Again and again, to the applause of liberals and leftists who long viewed him skeptically, he has promised an administration that, fully realized, would be the most progressive in decades: trillions more in coronavirus stimulus spending, a climate plan backed by the authors of the Green New Deal, and perhaps even a public-health-insurance option. But he may also be one of the few remaining members of that progressive coalition in D.C. who think an agenda like that could be passed without first quickly abolishing the legislative filibuster. At the very least, he wants to try and work with post–Donald Trump Republicans first, before his party moves to strip the Senate minority of the ability to effectively veto legislation. Many liberals fret that even if Biden wins and Democrats take back the Senate, he won’t have that luxury — that he would have to make a choice early in his presidency whether to embark on a truly expansive administration that stretches the landscape of legislative possibility, or a restorationist one, which rebuilds self-restricting norms after Trump’s destruction. Having it both ways is a way of achieving neither, they worry. But that concern is unlikely to stop Biden — who still considers himself a consummate man of the Senate whose 36 years in the chamber give him unparalleled knowledge of its inner workings — from trying. “We can do a great deal if we just start talking to one another,” he said on a private Zoom call with 20 donors in mid-July. “Politics has become so dirty, so mean, so personal, it’s hard to get anything done.”

The fight over replacing Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Supreme Court is likely to make the battle over the filibuster — which had already been shaping up as a defining intra-Democratic argument of a possible Biden presidency — even more intense, evaporating much of the remaining faith progressives may have had in a traditional approach to Senate procedure, let alone bipartisanship. Just a day after Ginsburg died, Democrats’ Senate leader, Chuck Schumer, a politically cautious pragmatist, stood with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as she called for the party to “commit to using every procedural tool available to us to ensure that we buy ourselves the time necessary.” “If Leader McConnell presses forward, the Republican majority will have stolen two Supreme Court seats, four years apart, using completely contradictory rationales. How can we expect to trust the other side again?” Schumer himself asked a few days later. But Biden took another tack: pleading with Senate Republicans. “We need to de-escalate, not escalate,” he said in Philadelphia. The next day, in Wisconsin, he insisted, “This is not a partisan moment, for God’s sake.”

Over the summer, buoyed both by Biden’s enduring polling lead and his work to bring the left wing of the party into his coalition, many liberals have allowed themselves to enjoy small windows of genuine hope even beyond his basic promise of ending the Trump years. Biden may be the man who in the 1990s sided with Republicans on a balanced-budget amendment to the Constitution, but here he was relying extraordinarily heavily on Elizabeth Warren as a behind-the-scenes policy adviser and hiring Bernie Sanders allies to his transition team. He wasn’t acting like a bureaucrat who expected to spend the next four years just undoing Trump’s executive orders domestically and rebuilding relationships abroad.

But there were, even then, contraindications. He gave Republican John Kasich a much bigger role at his nominating convention than the progressive Ocasio-Cortez. When Barack Obama used his July eulogy for John Lewis to call for an end to the filibuster — a “Jim Crow relic” — if that’s what it took to pass voting-rights legislation, it seemed to many Democrats that the tide was turning. But Biden soon after gave an interview, responding that “I don’t think we have to,” since Democrats would win back the Senate and enough Republican lawmakers would change their ways in the post-Trump era. And while he allowed it might come to that — “What I said was that if, in fact, they are as obstreperous as expected, we’d have to get rid of the filibuster,” he told CBS News’ Errol Barnett, adding, “if there’s no other way to move, other than getting rid of the filibuster, that’s what we’ll do” — he also emphasized the risks: “The filibuster has also saved a lot of bad things from happening too.” His closest allies have echoed his ambivalence. “Joe Biden is someone who has shown a willingness, when history compels it, to change,” said Delaware’s Chris Coons, who holds Biden’s former seat and who is the single senator closest to the former vice-president, whose compromise-friendly political sensibilities he shares. But history does have to compel it first, Coons continued, and until then, a temperamental moderation would probably prevail. “We are risking the possibility that the blowback could be terrible. When FDR tried his court-packing scheme, he lost his majority.”

Biden has also stood by as aides and advisers send signals that he may already be worrying about the state of the budget deficit, still long before the election, and with the country mired in a generational economic crisis — not to mention its death toll of more than 200,000. In August, one of Biden’s economic advisers told Vox his recovery plan likely could not be passed using budget reconciliation, a Senate maneuver that lets specific kinds of spending legislation pass with a simple majority instead of the usually required 60 votes; it would need bipartisan support. Two days later, Ted Kaufman, one of Biden’s closest political allies for decades and his successor in the Senate, was fretting about the ballooning deficit to The Wall Street Journal. “The pantry is going to be bare,” he said. “We’re going to be limited.” Alarmed, Sanders responded: “He is dead wrong.”

In these dire national circumstances, at this desperate moment, facing an unthinkable opponent and united behind a common-ground-above-all-else candidate, it’s possible to see how a campaign could survive these kinds of ideological tensions — hoisting a cavernous enough tent that Sanders and Kasich could speak on the same convention night, sharing explicitly contradictory messages. But especially now, after Ginsburg’s death, it’s all the more difficult to see how an administration could do the same — delivering on a progressive wish list without at least bending the traditions of the Senate and challenging decades of convention about the size of the budget deficit. And as the summer gave way to fall, some liberals began to fear that the nominee’s rhetorical gestures of bipartisanship — which he both believes in and views as crucial to appeal to regretful Trump voters — were falling short of the moment. By all accounts, Biden vehemently disagrees, especially as he tries winning over voters interested in his everything-will-calm-down-soon pitch. The former vice-president regularly rips into Mitch McConnell’s Republicans for enabling Trump, but he also believes the political ground has been fundamentally shifting in the Trump era and that it will settle again after November, bringing some Republicans back to the negotiating table in genuine good faith with Democrats’ top deal-makers.

Still, evidence is scant that a Republican firmament that was so effective in blocking Obama’s agenda would have such an extreme change of heart with Biden’s just because Trump would be gone — look at their eagerness to line up behind McConnell to confirm Ginsburg’s replacement, even before the nominee’s identity was known, and even when doing so directly contradicted their 2016 statements about Merrick Garland, Obama’s nominee to replace Antonin Scalia.

“I have great confidence in Joe Biden’s abilities, his experience in the Senate, and as vice-president. However, I think we have to look at the Senate now, as compared to when he was a senator,” Harry Reid, the former majority leader, told me this summer, before Ginsburg’s death. “In my opinion, the Senate has been terribly damaged by McConnell and his Republicans. The Senate is no longer a great debating society — it’s a great burial program.”

Reid, who is now retired and living in Las Vegas, has become a crusader against the filibuster. He speaks with Biden frequently, and he has laid out the case against it to Biden’s top aide, Steve Ricchetti. There’s certainly no promise that Democrats could fully eliminate the filibuster even if they do win the Senate, since a handful of moderates have resisted such a move, and they would need 51 senators to support it. They could also try to find a half-measure that weakens the maneuver without fully destroying it. Still, to Reid, Biden’s “first Congress could be as exciting and productive as Obama’s first Congress,” which included passing Obamacare, an economic stimulus, and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street regulation law. But a lot depends on how aggressive he is in the first months of his presidency, especially since he would certainly enter office with fewer Democratic senators to work with than Obama had. Biden “should be given a little time to see if he can work things out the old-fashioned way,” Reid said. “But in my opinion, he can’t let too much time go by in trying to cajole, work with the Republicans. Because pretty soon, the first session’s gone,” he continued. “Look at what happened in Obama’s first Congress. If you wipe that out, there isn’t much there.”

That Biden, who started talking about defending the sanctity of the Senate almost as soon as he got there as a 30-year-old, is now even open to having this argument — rather than insisting the filibuster must stay no matter what and recoiling at unilateral action — is itself a significant shift. Biden has always considered himself a deal-maker. Speaking to the Washingtonian for his first big magazine profile in 1974, he was already complaining about how partisan and unproductive the Senate had become. “My kids are going to talk about me fifteen years from now as being a member of the House of Lords if the Senate keeps going the way it is today,” he said. At that point, he had spent just a year in the chamber, where dust was still clearing from southern racists’ filibusters of 1960s civil-rights measures. Thirty-one years after that interview, as the Senate considered eliminating the filibuster for judicial nominations while George W. Bush was president, Biden warned from its floor that “the proposed course of action that we’re hearing about these days is one that has the potential to do more damage to this system than anything that’s occurred since I have become a United States senator.” Around that time, he told The New Yorker that the filibuster “is what makes the difference between this body” and the House. (There is no higher insult to a senator.)

But when, fed up by the impossibility of progress, Reid in 2013 changed Senate rules using the so-called nuclear option, making it so that most presidential nominees only required approval from a majority of senators present, down from 60, Biden kept mostly quiet. In private, Biden was softening. Then vice-president, he helped get Democratic senators in line for Reid’s change, according to officials involved behind the scenes. (Meanwhile, McConnell told Reid “You’ll regret this” and four years later eliminated the rule for Supreme Court justices so he could elevate Neil Gorsuch. Just then, Coons and Maine Republican Susan Collins got 59 colleagues to sign on to a letter defending the legislative filibuster.) Last month, Biden chose as his running mate Kamala Harris, who said during her own presidential campaign that she would favor axing the filibuster if it got in the way of passing the Green New Deal.

Nonetheless, he doesn’t bring up the filibuster without being directly asked about it, and his aides don’t either. This is, in part, because few of them think talking about it now is sound politics before the election. Trump and McConnell have both already tried using the filibuster’s possible elimination as a political cudgel. (Sleepy Joe wants to rig the rules so his violent socialist posse can force its radical agenda on your peaceful suburb!) Republicans still think they can hold the Senate or keep liberal gains to a minimum — for Democrats to reach even 53 seats would mean gaining seven in November, factoring in Doug Jones’s likely loss in Alabama. And conservatives are now hoping to use the Court fight to energize base voters and save some GOP lawmakers they’d previously lost hope of keeping in Washington, like Arizona senator Martha McSally and Colorado’s Cory Gardner.

Biden’s allies also rarely engage with left-wing backers who are concerned that Biden would be limiting his own agenda by committing to negotiation with Republicans: He has been pushing ambitious proposals on everything from immigration, health care, gun control, and infrastructure to coronavirus-recovery provisions including housing investments, insurance expansions, and trillions of dollars in clean-energy programs. But while some versions of some pieces of this agenda could plausibly be passed using reconciliation — say, some expansions to health-care coverage, targeted economic stimulus measures, a carbon tax — it would likely mean shrinking legislative ambitions and taking a more conventional approach to the presidency, oriented around proving the premise that Biden is the answer to D.C.’s typical partisan gridlock. This view still provides plenty of reason for optimism among some of Biden’s top supporters: “The trifecta of Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, and Joe Biden is just the ultimate partnership,” said Steve Israel, the former Long Island congressman who ran House Democrats’ campaign wing. “Pelosi is one of the most strategic thinkers, Schumer has among the sharpest elbows I’ve seen, and Joe Biden is all about relationships.”

And while liberals can argue a pragmatic case for abolishing the filibuster — nothing, no matter how progressive, will get done as long as it stays in place — those close to Biden see an equally pragmatic case for preserving the supermajority requirement too.

Democrats will probably keep the Senate in a President Biden’s first midterm if they take it with any margin this fall — more vulnerable Republicans are up for reelection in 2022 — but they are terrified of what an unrestrained conservative government might do after that, especially if the Court is slanted so heavily in their favor for decades to come. The thought experiment doesn’t take an immense amount of imagination. In his four years in office, Trump only passed one marquee piece of legislation — his tax cut — and only did so using reconciliation; his longest-lasting political legacy is likely to be the appointments of Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Ginsburg’s replacement, as well as hundreds of right-wing lower-court judges. This was made possible by the elimination of the filibuster for their nominations. If the rule hadn’t applied to legislation under Trump, Republicans easily could have cut funding for Planned Parenthood and Social Security, rolled back even more financial-industry regulation than they did, further loosened restrictions on gun access, fully reversed environmental protections like the Clean Water Act, and, most prominently, eliminated the Obama era’s central accomplishment. “The Affordable Care Act wouldn’t exist today if there were no filibuster,” said Obama’s first director of legislative affairs, Phil Schiliro.

There is one legislative strategy that might allow Democrats to preserve their progressive ambitions and which could protect against the risk of future blowback, but Biden’s top allies never ever address it in these terms: an elimination of the filibuster, followed by the passage of a wide range of democracy reforms that have already been approved by the Democratic House and command enthusiastic support among progressive activists. These include automatic voter registration and an end to partisan gerrymandering. And the dream also has a next step: passing statehood for Washington, D.C., and granting Puerto Ricans the right to vote for it — moves that could hand Democrats a handful of new Senate seats and Electoral College votes. Many Democrats argue that these reforms are necessary in principle — that they protect the country’s experiment in democracy by guaranteeing citizens’ ability to vote, and that they minimize the possibility of long-standing minority rule — as in today’s Senate and presidency, which are both led by the party that won fewer votes in the previous election. But they serve a strategic partisan purpose as well, making Republican Senate majorities less common by rebalancing the Senate and Electoral College away from smaller rural states so that each is contested in what is, at least roughly speaking, a fair fight. Of course, it would almost certainly take the elimination of the filibuster to pass such measures in the first place.

The final maneuver in some versions of this vision, which Biden has outright opposed, might now have some new purchase too: adding left-leaning justices to the Court unilaterally, in yet another echo of FDR. Biden, who argued in July 2019 that Democrats would “live to rue that day” that they packed the court, insisted after Ginsburg died that the Senate must “cool the flames that have been engulfing our country. We can’t keep rewriting history, scrambling norms, and ignoring our cherished system of checks and balances.”

But it’s not clear that his whole party, including in the Senate itself, agrees. Harris, for one, indicated during her primary campaign that she would at least be open to expanding the court. And soon after news of Ginsburg’s death, liberal Massachusetts senator Ed Markey tweeted, “Mitch McConnell set the precedent. No Supreme Court vacancies filled in an election year. If he violates it, when Democrats control the Senate in the next Congress, we must abolish the filibuster and expand the Supreme Court.” Biden’s camp was unamused; none of Markey’s colleagues immediately agreed with him, at least in public.

The filibuster dilemma, at least, probably can’t wait long to resolve. If Democrats take the Senate, Biden wins, and Trump concedes, the new president, Schumer, and Pelosi will presumably begin discussing all of this before the end of November, even if McConnell waits until this lame-duck period to confirm Ginsburg’s replacement. Such a move would almost certainly further inflame even many moderate Democratic senators, whose patience with McConnell has long since run out, and whose appetite for procedural changes may grow accordingly. Their first topic of conversation may be which lawmakers Biden will poach for his Cabinet; the second will be what laws they should try passing first and how they should respond to the changes on the Court. Biden hasn’t yet committed to any specific order for his agenda, insistent not to get ahead of himself and conscious of how much the world could still change before January, though he has referred to a huge array of proposals as top priorities. For months, he said one of the first things he’d do would be to rejoin the Paris climate agreement, which requires no congressional input. On a private call with Milwaukee-based supporters in July, he was asked to identify an area where he could work with Republicans in his first 100 days in office, and he replied there was a political opportunity in the clear majority of voters who want to “deal with systemic racism.” But first Democrats will likely first come under immediate pressure to pass another round of recovery legislation to respond to the economic and health havoc the virus may still be wreaking on the country.

Biden often talks about how his first job in the Obama years was to round up GOP votes for the new president’s economic stimulus plan in early 2009, and the parallels here would be clear enough that it’s not hard to envision Biden pursuing a handful of Republican aisle-crossers almost immediately. If he needs as many as eight or nine GOP votes, the obvious place to start around the time of his inauguration in January would be that party’s outliers, beginning in Maine: Collins was one of just three Republicans who voted for Obama’s stimulus. But if Democrats control the Senate in January, it almost certainly means Collins has lost her seat to Sara Gideon, the Speaker of Maine’s statehouse. So if she’s not an option, the focus will likely turn to Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski, who will probably be in the middle of another round of the perennial Washington speculation that she could leave the GOP and become an independent. (Collins and Murkowski were the only two Republican senators to state their opposition to seating a Ginsburg replacement before the election, opposing their party line.) Many Democrats hope that Mitt Romney, the only Republican to vote to convict Trump during his impeachment trial earlier this year, would also be a reliable negotiating partner in the charred landscape of a post-Trump Washington, but his decision to back Trump and McConnell on the Court vacancy blunted these hopes. And from there, the list grows even murkier. People around Biden sometimes mention somewhat independent-minded senators like Nebraska’s Ben Sasse as possibilities, though the conservative may be especially opposed to the kind of massive spending increase a full-scale recovery bill might entail. Biden would likely also reach out to Rob Portman, a relative moderate whom, according to people familiar with the interaction, Biden called to congratulate on his reelection on the same night Trump won in 2016, just as the Democratic Party was melting down.

But Biden isn’t the only one who remembers early 2009. While he thinks back on those early days fondly, Republicans widely see them as a warning not to play ball: The three GOP senators who went along with Biden and Obama 11 years ago faced immediate backlash within the party. One lost his subsequent primary; another then retired. Collins was the third, and the parties have been sprinting apart ever since. If Biden and Schumer can’t get 60 votes on this first bill, they may face an immediate crossroads. The politically safest option would likely be to try and pass the legislation using only Democratic votes, with budget reconciliation. Some Republicans, eyeing the potential Biden years warily, are quietly hoping this, rather than a more radical reshaping of the chamber, would be the plan — hopefully, they’ve pointed out that budget rules may be subject to especially liberal interpretations in the coming years, since the Senate’s budget committee will almost certainly be run by Sanders. If this works, Democratic leaders might go back to their drawing board and return to the Senate with another proposal that might have some bipartisan attraction — but which couldn’t be passed with reconciliation alone — depending on how willing to shake the Trump years their colleagues across the aisle prove to be. It might be on background checks for guns. Yet if Biden and Schumer are turned away decisively enough by GOP senators that they think this would be a waste of their energy, and that Biden’s entire agenda is therefore imperiled, they could decide it’s time to gauge the Democratic caucus’s receptivity to a broader change.

It’s been growing more receptive. Oregon’s Jeff Merkley, for one, often thinks back to the early days of Obama’s administration. The genial but reserved progressive was just a few months into his first term as a senator when someone slipped him a rude welcoming to Capitol Hill. It was a memo written by GOP pollster Frank Luntz instructing congressional Republicans on how to talk about the new president’s health-care proposal. The 28-page document pushed lawmakers to call Obama’s plan a “Washington takeover,” because “takeovers are like coups — they both lead to dictators and a loss of freedom. What Americans fear most is that Washington politicians will dictate what kind of care they can receive.” Never mind that Obama’s bill was still being written, or that the new president had been going out of his way to accommodate the GOP — including meeting with his vanquished opponent John McCain and his close ally Lindsey Graham during the transition period and tapping three Republicans for his Cabinet. To Merkley, the lesson was obvious: Republicans were not acting in good faith and would clearly block Obama’s plans by whatever means necessary. For years thereafter, he stewed as Republicans’ stonewalling grew all the more blatant. Now, Merkley often starts conversations with colleagues by asking how they would fix the Senate. It rarely takes long for the filibuster to come up. Merkley has been meeting privately with colleagues to outline the filibuster’s history and the modern argument against it. He says he’s not interested in creating a system where any majority can bulldoze any minority — he wants to restore out-of-power party senators’ ability to realistically propose amendments to legislation — but that his “goal is to return to a functioning Senate.”

As Merkley has pushed rank-and-file members, even some of the caucus’s more prominent moderates have been surveying the frosty Senate landscape and acknowledging it may be time for a change. Minnesota’s Amy Klobuchar “has evolved on this topic,” especially as negotiations over virus recovery legislation have stalled, she told me over the summer. Pennsylvania’s Bob Casey, who said Merkley recently pitched him in his private office, has come around to being open to eliminating the filibuster, after opposing that kind of move “probably a year ago, or two years ago.” And when Coons — who spearheaded the 2017 letter with Collins — told Politico he was no longer ruling out such a move in June, Washington insiders saw it as the clearest sign yet of a real shift.

Still, it would take 51 senators to change the rules, and the path to get there remains thorny. (Schumer could force the change with a vote whenever he wanted, in theory, once he is confident he could get to 51.) For one, if Democrats do return to the majority in January, it’s because a group of mostly moderates will have ousted Republicans, and some candidates have been cagey on the topic — the Democrats in Maine, Montana, and Iowa, and one of the Georgian candidates, have said they’re open to the filibuster’s end, but their counterparts in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Colorado haven’t gone as far, and others, like in Arizona and Texas, and the second Georgian, have dodged. Meanwhile, at least six sitting Democratic senators have voiced opposition of their own. This includes Senate veterans like California’s Dianne Feinstein and younger liberals like Cory Booker, who are generally considered persuadable by the anti-filibuster crowd, and also centrists from politically diverse states, like West Virginia’s Joe Manchin, Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema, Maine’s Angus King, and Montana’s Jon Tester.

Manchin is widely considered the hardest “No.” About a week before Obama spoke in Atlanta, CNN asked Manchin, who is open about how miserable he is in Washington and how eager he is to leave, for his thoughts on his colleagues’ push to change the rule. “That’s bullshit,” he said. For years, Manchin has told fellow senators that the day the filibuster is eliminated is his last day in the Senate. People close to him believe him — they remember how he nearly quit the body last year. But they also say that if anyone could get him to budge, it might be Biden, who was the only person in the last White House with whom Manchin had a decent working relationship. If there’s anything Manchin is more obviously upset with than D.C. itself, after all, it’s McConnell.

Klobuchar’s thinking is still more typical. The filibuster, she said, “is leverage” to be used against recalcitrant Republicans — if GOP members know Democrats can pull the trigger on it anytime, they may be more willing to work across the aisle on some of Biden’s priorities. If they fail to get Republican buy-in on an initial recovery bill, Biden and Schumer may begin dropping hints about changing the rules, to see if that will win over any nervous conservatives on the next legislative push. Embedded in this strategy would be the threat of one of Republicans’ greatest fears: that a majority-rule system would pave the way to statehood for D.C. and Puerto Rico.

Already, some Democratic lawmakers have pressured Biden’s top aides and transition team to make this possibility more explicit as a way to either spur GOP cooperation or genuinely reform the electoral system. And if Biden makes it to the spring of 2021 without new big-ticket laws on the books, these allies widely think it would be time to force the issue by daring Republicans to block a barrage of popular legislation, perhaps on climate, health care, or immigration. To convince enough moderate Democratic senators to sign on to eliminating the filibuster, they would first have to make it politically unavoidable: It would “require there being an effort to pass something two or three times and making Republicans look completely unreasonable for blocking it — exposing that the Republicans are acting in bad faith,” said Brian Fallon, a Democratic operative and former Schumer aide.

Though few will yet say it out loud, some Democrats close to Biden think they know which issue might end up being the final straw. It’s a matter of clear moral authority: the sprawling voting-rights legislation now named after Lewis. Which Democrat would oppose going all out to enact it, especially after a brutal election marked by historic voter suppression and after Obama’s speech? That eulogy may as well have been written in part to force this conclusion. “I served very closely with Barack Obama,” Reid said. “Barack Obama doesn’t do anything impulsively. He’s a very thoughtful, deliberate person.”

When certain Democratic lawmakers feel like venting, they pull up a one-and-a-half-minute video filmed in the summer of 2015. The HuffPost clip features Graham — who was then known best as McCain’s wingman but who is now famously among Trump’s most loyal defenders — tearing up in the back seat of a car in Iowa. “The bottom line is, if you can’t admire Joe Biden as a person, there’s probably — you got a problem,” Graham says, recounting a conversation the pair had after Biden’s son Beau died a few weeks earlier. “He’s the nicest person I think I ever met in politics. He is as good a man as God ever created.” No Republican transformation of the past five years has shaken Democrats more than Graham’s, which they generally see as a sign of that party’s complete detachment from reality, let alone any intentions of cooperation. In 2016, and then again in 2018, Graham, now the chairman of the powerful Judiciary Committee, promised not to seat a new Supreme Court justice in 2020, even asking Democrats to “use my words against me” in arguing his position. He reversed it as soon as Ginsburg died. During Trump’s impeachment, Graham laid into Biden and his surviving son, Hunter, for their work in Ukraine. This summer, not one of the current or retired Republican senators that I reached out to would agree to talk with me about Biden. “The Senate Joe Biden left is not the Senate that exists today,” sighed Barbara Boxer, the California Democrat and Biden friend who retired from the Senate in 2017.

This is partly thanks to Trump, but it’s also a story of massive turnover. If Biden wins, he would face a Senate in which well over two-thirds of the 100 members joined in the time since he departed. As few as 27 could be left over from his time there, depending on the breadth of Democrats’ victory. Not only are his relationships less profound with newer members, but many of these lawmakers have never served in a Senate that’s accustomed to churning out consensus legislation. “There’s a cadre of really hard-right senators, many of whom are very ideological, doctrinaire. That’s going to be difficult to deal with. In Joe Biden’s day, you could have differences on policy and ideology, but sometimes you wouldn’t have both,” said Casey. “It’s going to be a lot harder to be the kind of president Joe Biden wanted to be 20 years ago.” Where relative moderate Kay Bailey Hutchison sat when Biden left the Senate, now yammers Ted Cruz. Democrat Mark Pryor has been replaced by Tom Cotton. Genteel conservative Bob Bennett long ago lost to right-winger Mike Lee.

But Biden has long been fond of telling anyone within earshot the story of how, early in his Senate tenure, then-Majority Leader Mike Mansfield taught him to never question another senator’s motives. In Biden’s mind, this and his years of experience would make him far more skilled a Senate maneuverer than any president in recent history. Though he is loath to criticize Obama, many in his inner circle were driven crazy by the former president’s unwillingness to indulge individual lawmakers’ wishes or quirks in the service of negotiating. Now, for all Biden’s talk about FDR, it’s become fashionable for Biden allies to quietly wonder if Lyndon Johnson might be a more accurate comparison for him. The schmooze-first Biden would be the first president with significant Senate experience since the arm-twisting Texan; Johnson rose higher in the chamber’s leadership, but his tenure there is still dwarfed by Biden’s three and a half decades. Reaching out across the aisle is Biden’s “default, natural position” after all this time, said Democrat Mary Landrieu, a former senator from conservative Louisiana.

This vision implies some Republican willingness to cooperate. At various points throughout his first term, a frustrated Obama talked about working with Republicans once their “fever broke,” but he stopped trying to make this case early in his second term. Biden, too, has stopped talking as much about a post-Trump GOP awakening as he used to. Last spring, in New Hampshire, he predicted, “You will see an epiphany occur among many of my Republican friends.” Now he’s more apt to complain about McConnell’s iron fist. But he still has hope that, as his friend the former Florida senator Bill Nelson recently told me, not “many [Republicans] are going to say, after Biden is sworn in, that they still want to stay back, wallowing around in this ditch of corruption and ill will that has been left by the immediate past president, Trump.” Coons, who speaks as much with Republican senators as any Democrat, sees reason for hope too. “When we get to January 21, the day after the inauguration, there will be a simple choice Republicans and their leader will need to make,” he said. “Will they be determined to keep Joe Biden from getting anything done? If that’s the case, we’ll need to make some very hard choices about how we’re going to get anything done.” But, he added, “I doubt that’s going to happen.”

That was before Ginsburg died, and any responsible conversation about this topic starts and ends with McConnell, who is likely to be reelected this fall and who controls his caucus. Though most Biden-era negotiation would likely ultimately be up to Schumer, Biden still regards his relationship with the Kentuckian as potentially instrumental. The pair was never particularly close during their shared quarter-century in the Senate, but people close to both of them still speak lukewarmly of their time negotiating in the Obama years. The year after his reelection, Obama joked at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, “Some folks still don’t think I spend enough time with Congress — ‘Why don’t you get a drink with Mitch McConnell?,’ they ask. Really? Why don’t you get a drink with Mitch McConnell?” Biden saw it differently, recognizing in the GOP leader a sparring partner he could understand. People close to him still smile at the memory of McConnell naming the Cancer Moonshot provision of a bill after Beau in the final weeks before Trump was inaugurated. McConnell, meanwhile, couldn’t stand Obama but thought he could speak the same language as Biden, so he often refused to deal with anyone else in the White House. “Obviously, I don’t always agree with him, but I do trust him implicitly,” McConnell said on the Senate floor during a December 2016 tribute to Biden, who was then widely assumed to be days from retirement. “He doesn’t break his word. He doesn’t waste time telling me why I’m wrong. He gets down to brass tacks, and he keeps in sight the stakes. There’s a reason ‘Get Joe on the phone’ is shorthand for ‘Time to get serious’ in my office.” The two met repeatedly during Obama’s term, often when the president dispatched Biden to strike an agreement to avert a shutdown or default or fiscal crisis. “If anyone can re-create the old magic, it’s some version of Biden and McConnell,” said Rohit Kumar, a former top aide to McConnell. “They have the muscle memory from that era, even if the muscle hasn’t been flexed recently.”

Still, on broader topics, Biden seldom had success with McConnell or his caucus, which is exactly why some Democrats suspect McConnell relished working with Biden to begin with. (Biden “is being honest in his desire to work with Republicans,” said Eli Zupnick, a former Democratic leadership aide who is now working with a constellation of progressive groups in advocating for filibuster reform. “But Republicans have no interest in working with him.”) The former vice-president often boasts of winning three GOP votes for Obama’s initial stimulus bill, but he initially went after far more than those three. After the Sandy Hook shooting, even his full-court press with the national political winds blowing in his favor couldn’t pull rank-and-file Republicans across the line on gun-control legislation. And though Biden was pursuing Obama’s preferred ends when he negotiated with McConnell, his results occasionally infuriated fellow Democrats who thought they could extract more from Republicans. At the first presidential primary debate last June, centrist Colorado senator Michael Bennet said Biden’s deal with McConnell to avoid the so-called fiscal cliff at the end of 2012 had been “a complete victory for the tea party.” Other Democratic senators shared this view, siding at the time with Reid over Obama and Biden in wanting their party to force GOP concessions by purposely holding out on a deal until after the “cliff” deadline, at which point Bush-era tax cuts would expire. A few months later, in 2013, Reid informed the White House that they should let him handle a looming government shutdown and not let Biden get involved. Reid was concerned the vice-president would swoop in and make a deal to reopen the government with McConnell, allowing the Republican leader to declare victory. Reid said he would instead call Republicans’s bluff and force them to cave after a few painful days of shutdown. Reid won.

People around Biden still think it’s worth trying to soften McConnell’s opposition. The Republican has embraced his role as the “Grim Reaper,” pledging to stop Democratic legislation sent to him by the House as long as he’s running the Senate. And some close to him have laid out plans to muck up Biden’s first year like they did Obama’s — “He went from walking on water to completely upside down,” one longtime McConnell lieutenant told the Associated Press this year. His move to immediately replace Ginsburg fit the pattern. But the optimists in Biden’s corner think, as the incoming president, he might still embrace the likelihood that, at 78 when he’s inaugurated, he will only serve one term and that his time to have an impact is short, so he can either get McConnell onboard or move on without him.

The senators whose politics most closely reflect Biden’s see the coronavirus crisis as a clear opportunity to prove the old Senate isn’t dead yet. “No one wants to write the story of how we still get things done! I will remind you: Four months ago, the single biggest spending bill since the Great Depression passed unanimously,” Coons said this summer, referring to the first coronavirus relief package. “From Sanders to Cruz, every single one of us voted for it. That’s stunning. It’s still possible to legislate in a bipartisan way in the face of crisis. We just did it.” And though present-day negotiations on pandemic relief have been at a standstill for months, Klobuchar predicted post-Trump progress: “Remember, there were Republicans working with us day in and day out on the different provisions,” she said. Then, “Poof, it all went away because the White House won’t come negotiate.” She pointed out that similar dynamics have tanked bipartisan work on infrastructure, immigration, election security, and background checks.

Her colleague Merkley is more skeptical. “Democrats should consider this an absolutely unacceptable state,” he told me recently. “That McConnell has a veto. That the wheel of the majority is being bent by the minority.” Others think it’s downright dangerous thinking. “Even if Republicans suffer a huge defeat on Election Day, they’ll still look back on their years of obstruction and see a net gain, and that is a correct calculation,” said Adam Jentleson, a former Reid aide and the author of a forthcoming book about the broken Senate. “The trump card for the Senate leader is always: Think of the team, don’t work with Democrats, and don’t give them a win. Because if we block them, our side stands to gain in the next midterms. And that trump card remains as operative as it was under Obama.” Nothing illustrates this more clearly than the rightward swing of the Supreme Court under McConnell’s watch, which started with his rejection of Garland.

The day before Biden accepted his party’s nomination at his virtual convention late this summer, I called Patrick Leahy. Leahy joined the Senate just two years after Biden — soon after Richard Nixon resigned — and the early-30-somethings bonded in a body dominated by far older men. Now an 80-year-old liberal entering the final two years of his eighth term, Leahy has been waiting out much of the pandemic at his Vermont farmhouse. He told me he’d been thinking about his and Biden’s early days in Washington. That was a time, he fondly recalled, when senators would mix across party lines inside the Senate’s clubby private dining room and when vice-presidents like Walter Mondale and George H.W. Bush would come to Capitol Hill and mingle too. In the last year, Biden has stopped openly yearning for this era after he came under fire for promoting his ability to work even with its segregationist senators, but Leahy said they had reminisced about it and that he still thinks it provides blueprints for the future.

Biden “knows how it could be done,” said Leahy. He “will remember those times. My guess is you’re going to see, as president, he’ll be far more, ‘Hey, boys and girls, come on down here. Why don’t you drop down here and let’s chitchat?’” Leahy, the fifth-longest-serving senator in history, understands that many younger voters, lawmakers, and Senate aides view this thinking as intolerably nostalgic. A veteran Democratic staffer who worked with the Obama White House recently sighed to me that “Biden, as VP, completely thought it was 1985 or 1988 and that he was still a chummy senator with the rest of them. He really thought it was an old-style Senate, and he didn’t see how much it changed.”

Biden’s closest allies concede that he’s never negotiated directly with fully Trumped Republican senators, or even with the latest version of his old friend Graham — the one now poised to oversee the process of yanking the judiciary far to the right by replacing Ginsburg with a conservative. They insist, however, that Biden’s eyes are open, both because he never stopped watching Washington closely and because he’s kept in touch with old colleagues. “He has no illusion of what it is like today,” said Leahy. “To get a two-thirds vote in this Senate to say the sun rises in the east would be difficult.” About a month later, after Ginsburg died, Leahy dodged when a Vermont reporter asked if he’d consider packing the Supreme Court in response to Republicans’ replacing the liberal icon. “I literally have not thought about it because it seemed so improbable,” he said. His use of the past tense stuck out; it may not seem so improbable now.

Still, as Leahy and I talked, he grew reflective about the changes he’d seen in D.C. in recent years. If he were working with a narrow Senate majority, a President Biden “would not make the mistake of thinking, Ah, they’re all Democrats. I can do whatever I want. He’s the sort of person who will think long term — that we’ve got to bring people together,” Leahy insisted. “I’ve served with 400 senators; I’ve seen a lot of it.” We were talking a few hours before two of those senators — Obama and Harris — were scheduled to speak at the convention. “I’ve seen a lot of it. Joe’s seen a lot of it. I think he’s going to want to go back to the way things are supposed to work,” Leahy continued. “I think there’s a yearning to get back.”