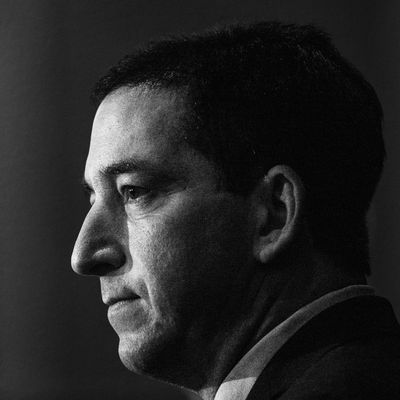

On Thursday, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Glenn Greenwald denounced The Intercept, the news outlet he co-founded six years ago, and announced his immediate resignation.

Best known for his reporting on NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, Greenwald claimed The Intercept was deliberately silencing him to protect Joe Biden. “The final, precipitating cause [of my resignation] is that The Intercept’s editors, in violation of my contractual right of editorial freedom, censored an article I wrote this week, refusing to publish it unless I remove all sections critical of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, the candidate vehemently supported by all New-York-based Intercept editors involved in this effort at suppression,” Greenwald wrote in a Substack post detailing his reasons for leaving.

Greenwald’s claim that The Intercept is in the tank for Biden baffled many of his now-former colleagues. “I don’t know of anyone on the editorial staff who really likes Biden,” Intercept national-security editor Vanessa Gezari told Intelligencer. Said another Intercept writer who requested anonymity, “If you look at the way lots of people on the site have written about Biden, the way [Greenwald] described the site and its vehement support of Biden is nonsense.”

And in a searing statement, Intercept editor-in-chief Betsy Reed mocked “the preposterous charge that The Intercept’s editors and reporters, with the lone, noble exception of Glenn Greenwald, have betrayed our mission to engage in fearless investigative journalism because we have been seduced by the lure of a Joe Biden presidency.” The Intercept is well known for its hostility to the Democratic Establishment in general and Biden in particular. Toward the end of the Democratic primary, The Intercept published numerous pieces about allegations of sexual harassment against Biden.

While Greenwald’s sudden resignation shocked both his colleagues and the broader world of media, his eventual break with The Intercept was all but inevitable. Greenwald, who did not respond to requests for comment, had already begun to plan his post-Intercept career. According to his Substack post, he has spent months in preliminary talks with other journalists and potential financial backers about starting a new media outlet. “I’m frankly surprised that he lasted as long as he did, because he’s clearly not a team player,” Intercept deputy editor Roger Hodge told Intelligencer. “He’s not somebody who can submerge himself in an organization and be part of a larger whole.”

Since the beginning, Greenwald had been separated from The Intercept’s U.S.-based newsroom, having lived in Brazil for over a decade. As a result, most of the staff had little to no interaction with him, according to Intercept staffers who spoke with Intelligencer. Even as The Intercept built itself into a full-fledged news organization — complete with robust editing like the kind Greenwald balked at — the co-founder remained apart, writing and publishing his columns with little to no editorial oversight. “He could have chosen to be a part of the mix, part of the conversation, the daily, weekly conversation about what we should be covering and what stories we were working on,” Hodge said. “But he never did that. He always held himself aloof from the newsroom and never, ever soiled himself with the day-to-day business of news gathering.”

Ryan Grim, The Intercept’s D.C. bureau chief, told Intelligencer that Greenwald’s conflict with The Intercept was part of a larger culture clash between Greenwald, a civil libertarian who objects in the strongest possible terms to any limitations on freedom of speech, and some of his younger left-leaning colleagues, who believe they have a responsibility to call out and try to shut down what they consider hateful or harmful speech. Greenwald wrote that he eventually concluded The Intercept itself embraced this so-called “cancel culture” in being reluctant to publish anything (like his Biden column) that might lead to accusations of aiding Trump and his supporters.

“There’s a phenomenon that exists everywhere, from corporate America to media, where the politics of younger people are different from the politics of some of the older people in these places,” Grim said. “The whole ‘woke debate’ that is played out endlessly on Twitter — he felt like there was too much of that going on at The Intercept.”

Once such example is a previously unreported incident from November 2018, when a group of Intercept staffers joined a virtual protest about Topic magazine, which was owned by the Intercept’s parent company, First Look Media. According to four First Look Media employees, the staffers went on the company’s Slack channel to object to Topic editor-in-chief Anna Holmes’s decision to publish a story about women who belonged to far-right groups, which included glamorous portraits of the women. The protest offended a number of senior Intercept editors, including Greenwald, who objected to the targeting of Holmes, a Black woman, and the suggestion that certain articles shouldn’t be published. (Nothing came of the protest, but Topic was shuttered in 2019 for unrelated financial reasons.)

Following the protest, Greenwald published a column that very pointedly criticized “the growing so-called ‘online call-out culture’ in which people who express controversial political views are not merely critiqued but demonized online and then formally and institutionally punished after a mob consolidates in outrage, often targeting their employers with demands that they be terminated.”

Another flash point occurred in June of this year, when Intercept reporter Akela Lacy publicly called out her colleague Lee Fang for “racist” behavior, including tweets about violence and Black Lives Matter protests. While Fang later released a thoughtful apology, many outside commentators saw him as a victim of cancel culture. In his resignation essay, Greenwald specifically criticized The Intercept’s “decision to hang Lee Fang out to dry and even force him to apologize when a colleague tried to destroy his reputation by publicly, baselessly and repeatedly branding him a racist.” Fang did not respond to a request for comment.

These generational and cultural dynamics have divided a number of newsrooms during the Trump administration. The most well-known example occurred earlier this year, when a number of New York Times journalists called out the paper’s opinion editor, James Bennet, for publishing an op-ed by Republican senator Tom Cotton that called on President Trump to deploy the U.S. military to major cities experiencing protests against police violence. The controversy over the op-ed cost Bennet his job and prompted Bari Weiss, a Times opinion editor who frequently inveighed against “cancel culture,” to publicly resign. In Greenwald’s view, The Intercept was founded in order to resist such censorious impulses but has since succumbed to them, as he put it in his resignation essay:

Rather than offering a venue for airing dissent, marginalized voices and unheard perspectives, [The Intercept] is rapidly becoming just another media outlet with mandated ideological and partisan loyalties, a rigid and narrow range of permitted viewpoints (ranging from establishment liberalism to soft leftism, but always anchored in ultimate support for the Democratic Party), a deep fear of offending hegemonic cultural liberalism and center-left Twitter luminaries, and an overarching need to secure the approval and admiration of the very mainstream media outlets we created The Intercept to oppose, critique and subvert.

The final straw for Greenwald was an editing dispute, though according to Hodge, it was less about specific edits and more about the fact that he was being edited at all.

“Glenn considers editing censorship,” Hodge said. “That’s his general position. He regards any editorial intervention as censorship.”

Hodge told New York magazine that Greenwald’s opinion columns were not subject to editing, but his reported pieces — including his investigations into animal cruelty — were subject to editing and legal review. Greenwald’s main editor on the nonpolitical pieces was Peter Maass, a veteran journalist who joined The Intercept shortly after its founding in 2014. In light of the high-profile, controversial nature of Greenwald’s planned column on Hunter Biden, Reed told Greenwald that Maass would edit the column.

On Tuesday, Maass sent a lengthy memo to Greenwald, outlining what he said were the draft’s strengths and weaknesses and suggesting that he adopt a sharper focus on media criticism rather than litigate questionable evidence of Joe Biden’s corruption based on purported documents from his son Hunter that had been published by the New York Post.

Greenwald viewed Maass’s memo as an attempt to censor him.

“I want to note clearly, because I think it’s so important for obvious reasons, that this is the first time in fifteen years of my writing about politics that I’ve been censored — i.e., told by others that I can’t publish what I believe or think — and it’s happening less than a week before a presidential election, and this censorship is being imposed by editors who eagerly want the candidate I’m writing about critically to win the election,” he wrote in an email to Maass on Wednesday morning, which he later published on Substack, where he’ll continue to write on a subscription basis.

Rather than revise the piece in line with Maass’s suggestions, Greenwald said he wanted to exercise an option in his contract to publish the piece outside of The Intercept. After Reed told Greenwald it would be “unfortunate and detrimental to The Intercept” if he published the story for another outlet, Greenwald decided to resign.

He joins a number of big-name writers who have recently left mainstream publications and found homes on Substack. In April, Rolling Stone writer Matt Taibbi moved his regular column to his personal Substack (though he continues to contribute feature stories to the magazine). And in June, former New York writer Andrew Sullivan launched his own Substack newsletter.

Not only may Substack be able to give Greenwald the kind of six-figure salary he had at The Intercept, it may give him something even more valuable: the ability to publish whatever he wants, free of any editorial oversight and colleagues who hold a different view of speech.

“Glenn’s idea of The Intercept was a chorus of Glenns, people who agree with Glenn,” Hodge said. “That was his vision, and that was why he became increasingly frustrated with the newsroom.”