The Democratic National Committee was hurting badly when Tom Perez took it over in early 2017. It was reeling from Donald Trump’s shocking win in 2016, and even plenty of Democrats didn’t trust it after the primary between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders. Perez, who was Labor secretary under Barack Obama, often privately likened his job at the DNC to repairing an airplane while flying it — especially in the early days, when Democrats were still struggling for money and losing the first few special elections of the Trump era.

The plane is still in the air: Democrats’ 2018 midterm performance and Joe Biden’s eviction of Trump — achieved by flipping five states the Republican won in 2016 — are clearly significant reasons for celebration for the party. But this month’s results have also exposed serious concerns for liberals and progressives moving forward. That’s not just true in Congress, where Republicans unexpectedly clawed back some of their deficit in the House of Representatives and are now favored to keep the Senate, and where Democratic lawmakers have been assigning each other blame for their losses for weeks. It’s also true across the country, where Democrats fell short in their attempts to flip state legislatures ahead of next year’s redistricting round.

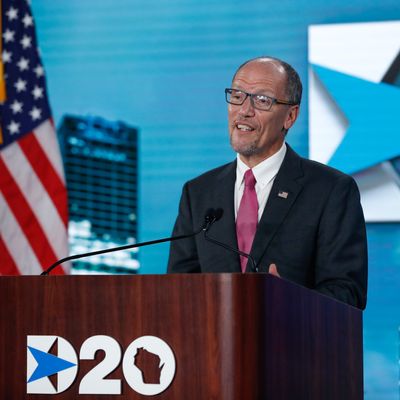

I recently spoke with Perez for an exit interview of sorts about his tenure and the party’s standing. We had less than 30 minutes to talk, but the former cabinet secretary — who’s occasionally been floated as a potential attorney general under Biden — argued that Democrats are actually in their best shape in years. He made the case that, contra the conventional wisdom, the party would not face a midterms wipeout in two years. He downplayed worries about the party’s performance with Latino voters, pointing instead to its problems in rural areas. And he acknowledged that four years ago he underestimated the depth of Democrats’ trouble.

This interview has been edited and condensed from an extended conversation.

In the early days of your tenure in 2017, we spoke often about how your primary goal was to beat Trump in 2020, along with finally fully funding the DNC and reestablishing trust in it after 2016. But there was also a lot of talk about making sure the party wasn’t just focused on the presidency after it finished the Obama years in rough shape not just in the Senate and House, but also in the states. So when you look at this month’s results — Joe Biden winning, but Republicans gaining in the House, possibly keeping the Senate, and maintaining power in state legislatures — what happened?

Well, I mean, when I look back, I tend to look back at where we were, and where we are now. When I took over the DNC in 2017, we had 15 governors who were Democrats. Now we have 24. We didn’t have the House of Representatives. We had lost a string of down-ballot races that had resulted in massive gerrymandering of a lot of state legislative seats. Our number of state attorneys general was in the teens. We’ve flipped over 400 seats in state legislatures. Eight legislative chambers have flipped. We have the U.S. House of Representatives. We were in the teens with AG’s and now we’re in the low 20s, which is really important. And then we won the biggest prize of all, which is flipping the White House. That happens roughly once a quarter century. And not only did we win the White House, I think when all votes are counted, President-elect Biden’s margin is going to be right where President Obama’s was in 2012. It’s a decisive victory, notwithstanding Donald Trump’s statements to the contrary. [Laughs.]

Now, were there seats I would have loved to have won in the House and Senate in 2020, that we didn’t win? Yeah, of course there were. When I look at the House side, I look at history, and when you look at the election cycle following a wave midterm year, parties historically lose seats in the following cycle. We saw that in 2012 after the Republicans won the House in 2010. We saw them lose, I think, eight seats, and the main reason it was only eight was because they had won so many state-level seats they gerrymandered the heck out of a number of districts.

Many of the gains you’ve just enumerated came over the course of four years, of course, but most were won in 2018, specifically. That was clearly a historic midterm year. But 2020 was significantly more disappointing down the ballot. Are you arguing that the difference between 2020 and 2018 was simply cyclical, at least when you look at the House? There wasn’t anything about the environment that surprised you?

We had record turnout in 2020, and that was a remarkable accomplishment. Joe Biden won more votes than anyone in the history of this country. He won a higher percentage of votes for a successful challenge to an incumbent president than anyone since FDR. At the same time, the last time we had a percentage of participation this high was 1900. Republicans came out in force as well. And if you look at the lessons moving forward, Donald Trump did bring out voters. Joe Biden built a broader coalition, and it was a coalition of hardcore Democrats, independents, and John McCain Republicans who understand that the party of Lincoln is no longer the party of civil rights. So we built a better coalition.

That will be a challenge for Republicans when Trump’s not on the ballot in 2021. He’s not on the ballot in 2022, or in 2023. And we have seen that his ability to drive turnout when he’s not on the ballot was far more limited: We were able to score decisive victories. Look at 2019 in Kentucky and Louisiana, those were two states where he showed up in the days leading up to those elections; he wanted to put himself on the ballot. What was on the ballot in those states, and what has been on the ballot every year, and continues to be, is health care. And now our safety, because of the coronavirus. The bottom line that has helped us win, up and down the ballot, has been that the majority of the American people have seen that we are fighting for the issues that matter most. In the middle of a pandemic you’ve got a Republican Party that wants to do away with coverage for people with preexisting conditions. COVID is the third-leading cause of death in America right now behind heart attacks — heart disease — and cancer. The common denominator throughout that has given us success dating back to 2017 has been the fact that we are fighting for the issues that matter most to people.

And I’m proud of the infrastructure we have built. I said very early on, I want to be a 57-state-and-territory party again. I want to make sure we’re organizing everywhere and competing everywhere. And we’ve been able to succeed in many, many places. We still have work to do. But we’ve built an infrastructure that’s very, very muscular. We built one of the most effective partnerships with a presidential campaign that has ever existed; it’s a model for cycles to come. We’re built to last. We’re far better off than we were four years ago.

Before we get into the infrastructure, I want to back up for a second. You just made the case that Republicans are going to have a hard time achieving Trump-level turnout in a post-Trump age, while Democrats — at least Biden — built a broader coalition. But clearly a lot of the “John McCain Republicans” you’re talking about gravitated to Biden and some others specifically because Trump was on the ballot, right? So how do you keep those people in the fold once Trump and his specter are gone?

I think Americans are sick and tired of being sick and tired. The American people want a leader with both empathy and compassion, a leader who is going to be a president for everyone. You know, Joe Biden isn’t going to be helping COVID victims only in blue states. He understands that he’s the president of the United States. And what we are about to do right now is repeat a situation we have found ourselves in multiple times.

Look at 1992. We were in a recession, we were losing jobs, we had massive deficits, and the American people elected Bill Clinton. When Bill Clinton left, we had surpluses as long as the eye could see, we had record low unemployment, the economy was humming. And that was what Democrats handed over to Republicans. In 2009, Joe Biden and Barack Obama were handed the Great Recession, the worst recession — then — of our lifetimes. And at the end of the Obama-Biden administration, we had the longest uninterrupted streak of private-sector job growth in American history, the most important addition to our health care, our social compact, since Medicare and Medicaid in the Affordable Care Act. And the economy was moving in the right direction. What does Donald Trump hand Joe Biden and Kamala Harris? A great recession unlike anything we’ve seen since the Great Depression. Deficits as long as the eye can see, attacks on health care, an economy that is not working. Donald Trump is going to be the first president since Herbert Hoover to preside over net job loss in his presidency. And with Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, here we go again: Democrats are picking up the pieces of Republican disasters for the third time in the last 30 years.

That’s all more or less undeniable, but then came the devastating midterms of 1994 and 2010. What’s the argument that — especially with such a small margin in the House now, after this month — the same thing won’t also happen in 2022?

Well, I think people are going to ask themselves in two years: Am I better off now than I was two years ago? That’s why Joe Biden is already at work tackling the coronavirus, on an economic plan that is going to “build back better,” that’s going to address peoples’ day-to-day challenges. So many people have lost a loved one, they’ve lost a job, they’ve probably lost hope. So what you’re going to see with Democrats in charge is we’re going to get to work on infrastructure. We’re going to get to work on fixing the coronavirus. That’s why the president’s lack of cooperation during this transition on the coronavirus is playing with lives. We all want to see these vaccines in place. The best way to help the American people right now is to do exactly what Jimmy Carter did in 1980: He called Ronald Reagan and said, “I want this to be the best transition ever, because I know the American people demand that, I know our situation demands that.” That’s what Donald Trump should do, but we know that’s not happening.

Let’s talk about the pandemic. Was it a tactical mistake for Democrats and down-ballot Democrats not to do more in-person door-knocking and on-the-ground organization in the general election until the very end?

We had record turnout! We’re going to be north of 150 million people turning out. I mean, we had a lot of folks that turned out. And I think we set a really important example of how to manage a pandemic, whether it was at the convention, or whether it was managing the campaigns. And one of the reasons why we were able to win, even though we had a limited number of cities where we were able to knock on doors, is that we had been building this organization for many years. I’ll give you one example. In Wisconsin, the investments began in 2017. We won all statewide elections in 2018. In 2019, under the very able leadership of the state party chair, Ben Wikler, we knocked on almost 300,000 doors. If you look back at 2015, it was just a small fraction of the doors that were knocked on in 2019. And when the pandemic hit, we had already built relationships, and we simply had to transform the method of communicating with these voters. But we weren’t talking to them for the first time. That’s the new model of organizing on the Democratic side.

And the other thing that’s really important is that we invested so heavily in data and technology, purchasing 150 million cell-phone numbers. I didn’t purchase them because I anticipated a pandemic back in 2017 and 2018. We purchased them because we know that you’ve got to meet the voter where they consume their news, and that is on their smartphone. So we had already developed a really good capacity to do digital organizing, and when the pandemic hit, those investments really turned out to be simply invaluable. And again, if you look at the Biden operation, the coordinated campaign was, like, 2,700 people. The largest pipeline of diverse talent for that coordinated campaign was Organizing Corps, which was an initiative that was put in place by the DNC in 2019. Roughly a quarter of the coordinated operation were Organizing Corps hires. And these were folks who were talking to voters as early as the summer of 2019 in cities like Milwaukee, Detroit, and Philly. We had our eye on the industrial Midwest, and Georgia and Arizona. We had an eye on the states that were going to be the critical 2020 battlegrounds long before 2020.

You mentioned the voter-data operation, which obviously informed a lot of your strategic decisions and projections about the race. You spent the last few days before Election Day in Texas, which is one state where a lot of internal data and public data gave Democrats plenty of reason for hope. That fell flat. A lot’s been said about the public polling, but is there a reason your internal expectations there were higher than the reality?

We did really, really well in the major metropolitan areas. We were off the charts in Harris County. We won Tarrant County, which I don’t know that we’ve ever done. [Ed. note: Lyndon Johnson was the last Democrat to win Tarrant.] In Bexar County, which is San Antonio, we ended up performing exceedingly well. The thing about Texas is, am I disappointed at the outcomes? Uh, yes, of course. I want to win everywhere. But — and this gets to the cultural transformation of our operation — it’s really important to take a long-term approach to our work at the DNC. In 2012, Barack Obama lost Texas by 16. In 2016, Hillary Clinton lost by nine points. We are poised to lose Texas by about five points. We are moving in the right direction. I said this on Election Night, and I will say it again: Texas is an undeniable battleground.

And look at Arizona and Georgia in 2016: We lost Arizona by a little under 4 percent; we lost Georgia by a little under 5 percent. When I got to the DNC, you didn’t need to be an analytics Ph.D. to look at those two states and realize that those two states — if we invested early — could absolutely be battlegrounds. Now look at Arizona: two Democratic United States senators. In Georgia, we still have a real shot: The January runoffs are going to be razor-thin. When I look at a place like Texas, we made tremendous progress. We continue to have work to do, and that work is in many of the rural pockets. We have to continue to take a page out of what Beto O’Rourke did in 2018: He was in every one of the counties of Texas.

Looking at the county-level results in Texas, one thing that certainly stuck out on Election Night was what happened along the Southern border. Do Democrats have reason for concern in the future when it comes to Latino voters there, and more broadly? Or do you have evidence that this year was an anomaly?

There are two or three dimensions to the answer to that question. Broadly — most broadly — if you look at the Latino vote in 2020, it was a solid vote for Joe Biden. Our goal was to match what Barack Obama did in 2012: He had 71 percent, in aggregate, of the Latino vote. We’re still gathering the data, but if we don’t hit that 71 percent, we’re going to be within a couple points. Arizona was one where there was a fusion coalition, but the linchpin of the victory in Arizona was the Latino vote. Seventy-five percent of Latinos voted for Joe Biden in Arizona. Smaller denominator, but look at Wisconsin: The margin was something like 56 points for Joe Biden, and it gave him a cushion of roughly 30,000 votes. When you win a state by 20,000 votes, you know … Same thing in places like Michigan and Pennsylvania. We underperformed in one county of Florida: Miami-Dade, which represents 3 percent of Latinos nationwide. We’re digging to understand. It has two specific groups: Venezuelans and Cubans. We won 70 percent of the Puerto Rican vote in Florida. Then look at Harris County, Texas: The Latino vote [for Democrats] was off the charts. Where we didn’t perform as well was in the rural parts of the state, and I spent time down there.

The question presented for Democrats moving forward is a broader question. We made real progress organizing in rural America, and the proof in the pudding is that we were able to — in many key battleground states — sustain and in some cases improve on some of the margins in some of the rural pockets with a very large denominator. Again, in Wisconsin and Michigan, etcetera, there were more voters that turned out in those little pockets of the state. And if we hadn’t invested in those states, in those areas, and Trump had gotten larger margins, that could have been a difference-maker. Our investments enabled us to avoid catastrophe, and to maintain the key to politics: to run up the score as best you can in places where you know you have a lot of votes. Dane County, Wisconsin, is a great example of that. But, again, holding our own in some of these rural pockets was really critical, and in places like Texas, with rural voters — white and non-white — we have to make sure we’re talking to them in meaningful ways about issues that matter most to them.

As you know, Latino voters are not a monolith. I don’t think there are any voters who are monolithic, but we need to understand that and build relationships. We had very specific engagement programs with African American men, with African American women, with Latinos and Latinas talking about issues that matter most to them: peer-to-peer conversations. And we’re going to continue to do that. We were able to do really well in this election because we did, in the aggregate, improve.

And with other critical constituencies: You look at the Native American vote in Arizona when you win by 11,000 votes. Look at Apache County, for instance, the home of Navajo Nation. We won that two-to-one. It’s obviously not as big as Maricopa County, but when you win the state by 11,000 votes out of 3.5 million cast, every single county matters. We had a really aggressive organizing presence in Apache County. With the Asian American vote, I’m really proud of the strides that have been made, in part because we understand that when you talk about the Asian American community, we’re talking about communities, plural. We’ve been very, very intentional about building relationships that reflect that understanding, and because our data systems enable us to do that. You know, when you meet a guy named Perez in Nevada, he might be Dominican, but he might be Filipino. And in 2016, we didn’t know the answer to that question, because our data wasn’t sophisticated enough. Now we have the capacity to know the answer to that question. So we can run an aggressive program that talks to Filipino voters, and they’re a huge part of our coalition, as are Latinos. But I want to know if the guy named Perez in Nevada is Filipino or Mexican American. That’s kind of important! And when I say we’re built to last, that’s what I mean. We’ve built the organizing infrastructure, the data-technology infrastructure, the misinformation-detection infrastructure, the communications infrastructure. I think we can sustain what we’ve done, but we’re not leaving anything to chance.