When Georgia was called for Joe Biden on November 13, I was instantly transported back to the last time my home state went Democratic in a presidential election. On Election Night in 1992, I was sitting near the television in Atlanta’s premier political watering hole, Manuel’s Tavern, when almost immediately after the polls closed Georgia was called for Bill Clinton. At the same place a few weeks earlier, I had noticed a lot of security around, and when I asked about it, the bartender laughed and said: “Yeah, Jimmy’s in the back room showing Clinton and Gore how to drive nails for a Habitat event they’re doing tomorrow.” In Atlanta, then and now, the 39th president was known simply as “Jimmy.”

It’s been a long road down and then back from that peak for Georgia Democrats. Clinton failed to carry the state in his landslide reelection of 1996. George W. Bush carried it twice by double-digit margins, and it went comfortably for Obama’s two opponents and then for Donald Trump four years ago. Down-ballot Democrats hung on to their ancient advantage in Georgia for a while, until a 2002 cataclysm when war hero Senator Max Cleland was upset in a smear-laden campaign, even as Governor Roy Barnes blew a big polling lead and a huge financial advantage to lose to Sonny Perdue (now Trump’s Agriculture secretary). Since then Democrats have struggled in statewide elections, losing them all since 2008 — until now.

Georgia is now what Ohio was earlier in this century and Florida has been before and after: the ultimate battleground state. It’s in a tight competition with Arizona for the closest 2020 presidential election state. But more importantly, Georgia will be the site of two January 5 Senate runoffs that will determine whether the Biden administration’s legislative ambitions will be crushed by Mitch McConnell. Why does Georgia have this strange general-election runoff system? Explaining that requires a stroll through the state’s stormy political history.

Before the U.S. Supreme Court’s “one person, one vote” decisions (notably 1962’s Baker v. Carr) of the early 1960s, Georgia was a bastion of Jim Crow stability. In state elections, it was dominated by rural racists who deployed the state’s own bucolic version of the electoral college, the County Unit system. From 1868 through 1960, it was the only state that had never been carried by Republicans. But with segregation under attack and the Johnson administration decisively supporting civil rights, Georgia was carried by Barry Goldwater in 1964, and then by the openly racist independent presidential candidate George Wallace in 1968.

In the meantime, the Georgia legislature passed a law requiring majority votes to win both primaries and general elections to ensure political white supremacy. For statewide races, the legislature appointed itself the final arbiter, which is how segregationist Democrat Lester Maddox (with the support of future governor and president Jimmy Carter) became governor in 1966 over Republican Bo Callaway. After that debacle the runoff law was amended to substitute voters for legislators in deciding elections with no majorities.

Like all of the Deep South, after 1964 and 1968 Georgia looked destined to succumb to Republican hegemony as the two major parties traded places on civil rights and other race-inflected issues; white voters re-consolidating in the more conservative party crucially outvoted Black voters who in many parts of the state were just securing the franchise. The Democratic share of the presidential vote in Georgia dropped from 46 percent in 1964 to 30 percent in 1968 to 25 percent in 1972. But then “Jimmy” performed a temporary political miracle by uniting southern Democrats across racial and ideological lines, until his whole enterprise came crashing down at the hands of Iranian hostage-takers and Ronald Reagan.

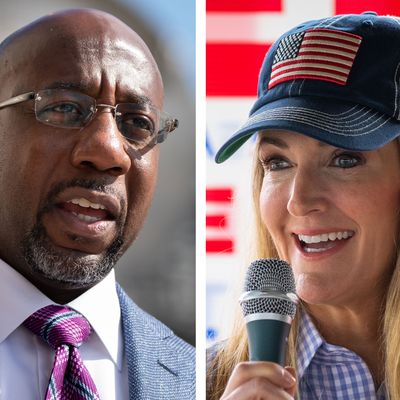

The slow climb back to competitiveness by Georgia Democrats was initially based on the Carter formula of combining a shrinking but still formidable redoubt of white rural voters with a reliable Black voting bloc and an emerging population of Black and white professionals, many of them recent transplants from north of the Mason-Dixon line or immigrants from around the world. In state elections, and in the brief moment when Clinton carried Georgia, it was sometimes just enough. But in this century, as Democrats reached rock bottom with white rural voters, they’ve discarded the Blue Dog conservatism necessary to reach them and begun slowly building a progressive party based on a multiracial urban and suburban coalition (with crucial support from small-town and rural Black voters). This is the coalition that delivered Georgia to Joe Biden, and will be mobilized for Democratic Senate candidates Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff in January.

Ossoff is a symbol of the Democratic tide that has made Atlanta’s increasingly diverse suburbs the fulcrum of Georgia politics. In his famous 2017 special election battle for a historically very Republican 6th congressional district in Atlanta’s leafy and affluent northern suburbs, he fell just short against Republican veteran Karen Handel. A year later Handel lost narrowly to Black gun control advocate Lucy McBath, who won convincingly in a 2020 rematch. In the adjoining 7th congressional district, Carolyn Bordeaux was the rare Democrat to flip a Republican House seat this year. And in a more fundamental sign of suburban evolution, the local governments in the two largest suburban counties north of Atlanta, Cobb and Gwinnett, flipped their leadership from white Republican men to Black Democratic women.

That development certainly got my attention. I went to high school in Cobb County, at a time when the local Democratic state legislator ran for reelection every two years on the racially loaded slogan of “Stop Atlanta at the [Chattahoochee] River!” And I lived in Gwinnett County at a time when every single local official was a Republican, and real-estate developers literally ruled the land. Suburban Atlanta has really changed, really quickly.

And the paragon of that change was and remains 2018 gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, the Atlanta legislator who proved once and for all that Georgia had changed just enough demographically and culturally that Democrats could appeal to Black and white voters with the same progressive message.

As I argued recently, the southern Democratic Party that young leaders like Abrams are building redeems the “New South” promise for which both Carter and Clinton represented a partial, and perhaps false, dawn. That Biden carried Georgia is a major first step. Democratic wins in the January runoffs would be even bigger. Republicans still control the Georgia legislature and will use their redistricting power to further entrench themselves. But soon enough, perhaps if Abrams runs again for governor in 2022, Georgia’s slow but steady emergence as a crucial battleground state will reach its omega point.