Democrats just secured full control of the federal government for the first time in a decade. When the party lost Congress back in 2010, many of its core constituencies were left holding IOUs. Labor left the Obama era without card check, climate hawks got neither “cap” nor “trade,” immigrant-rights groups never collected on their promised path to citizenship, and advocates for gun control and myriad other progressive causes were similarly stiffed.

In the years since, the party’s debts to its coalition have only mounted. Among other things, Joe Biden enters office having promised to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, enact a wide array of collective-bargaining reforms, pass a new voting rights act, grant statehood to Washington, D.C., and put the U.S. on a path to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

But he will do none of this unless all 50 Senate Democrats agree to abolish the legislative filibuster.

Multiple members of Chuck Schumer’s caucus have said they are committed to preserving the Senate’s de facto 60-vote requirement on major legislation. West Virginia senator Joe Manchin said on Fox News in November, “I commit to you tonight, and I commit to all of your viewers and everyone else that’s watching … I will not vote to end the filibuster.”

Some dispirited liberals took Manchin at his word. Senate Republicans did not.

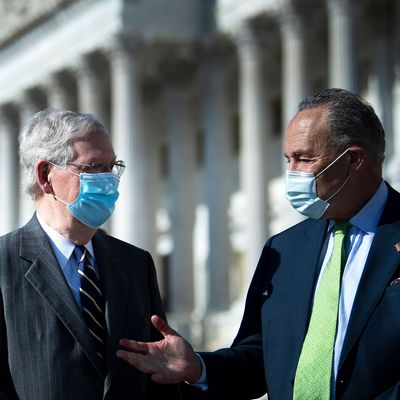

In fact, Manchin’s vow notwithstanding, Mitch McConnell is so concerned that his own obstruction will drive Democrats to “go nuclear,” he is threatening to paralyze the Senate until Chuck Schumer agrees to take filibuster elimination off the table.

The Democratic Party’s majority in the Senate hinges on Vice-President Kamala Harris’s tie-breaking vote. But Harris cannot break ties on the upper chamber’s committees. For this reason, among others, to get the new Senate up and running, Schumer and McConnell must agree to a “power sharing agreement” that establishes rough procedural guidelines for how the body will operate. They have yet to reach such an agreement, largely because McConnell insists that it include a provision mandating the preservation of the legislative filibuster.

To their credit, Democrats are refusing to preemptively forfeit their main source of leverage in interparty negotiations. As Politico reports:

Many Democrats argue that having the threat of targeting the filibuster will be key to forcing compromise with reluctant Republicans. They also believe it would show weakness to accede to McConnell’s demand as he’s relegated to minority leader.

“Chuck Schumer is the majority leader and he should be treated like majority leader. We can get shit done around here and we ought to be focused on getting stuff done,” said Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.). “If we don’t, the inmates are going to be running this ship.”

Tester is accountable to a constituency that backed Donald Trump last year by more than 16 points. And he is so riled up by McConnell’s temerity, he has apparently taken to viewing the Senate as a prison ship aboard which Republicans are mere inmates.

But the Senate GOP is equally adamant about disarming the majority before major legislative battles commence:

Republicans say that the time to commit to keeping the filibuster is now, not at a moment of political fury over legislation that the minority blocks. Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) said the GOP simply wants to hear Schumer say “that we’re not going to change the legislative filibuster.”

“You want to do it before there’s an emotional, difficult, controversial issue. So that it isn’t issue-driven, it’s institution-driven,” said Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine).

Another way to phrase what Collins and Graham are saying: “You want to fight for the filibuster’s preservation while it’s still just an abstract question of Senate procedure — not when a core Democratic constituency is mobilized behind a concrete policy goal, and realizes that this arbitrary affront to majority rule is the thing standing between them and historic change.”

Manchin may have vowed not to eliminate the filibuster. But months before his Fox News comments, the West Virginia senator expressed openness to reforming the convention, saying, “I’m interested in listening to anything because the place isn’t working.” And there are a great many ways to effectively eliminate the filibuster without officially doing so: Democrats could simply restore the requirement that a faction must speak continuously from the Senate floor in order to sustain a filibuster; or they could push non-budgetary legislation through the special budget-reconciliation process (that forbids filibusters), and then allow Kamala Harris to overrule the Senate parliamentarian when she objects to the bill’s ineligible content; or they could create a new exemption modeled on budget reconciliation that says, for example, “bills that expand voting rights cannot be filibustered.”

Barack Obama and Congressman Jim Clyburn have already characterized the filibuster as a tool of white supremacy, one that enabled the South to obstruct civil-rights legislation for years. If Republicans obstruct “the John Lewis Voting Rights Act,” the pressure on Senate Democrats to use the power at their disposal to fortify democracy — after the GOP subjected the nation to four years of democratic backsliding, and McConnell subjected Barack Obama to all manner of procedural hardball — will be immense. This reality, combined with the aforementioned existence of ways to abolish the filibuster without formally doing so, is likely what has McConnell & Co. so worried.

It’s worth noting that the abstract, “institution-driven” argument for retaining the filibuster is extremely weak. Not only is the filibuster absent from our Constitution, the Senate’s 60-vote threshold plainly contravenes that document’s intentions for the upper house. The framers did consider including a supermajority requirement for passing legislation through the Senate, but decided against it; after all, the constitutional system they designed already imposed a wide array of veto points on the legislative process (to become law, a bill must make it out of committee, then out of one chamber of Congress, then the other, then get signed by the president, and then, in many cases, upheld by the Supreme Court). Even without the filibuster, it would remain more difficult to pass laws in the United States than it is in any other advanced democracy.

What’s more, the filibuster is not even an actual Senate tradition. It was only in the last two decades that the upper chamber began imposing a 60-vote threshold on all major bills, rather than reserving the filibuster for exceptionally divisive fights. The filibuster’s defenders insist that the rule facilitates cooperation and bipartisanship. Yet the era of the 60-vote threshold has also been one of the least bipartisan and most dysfunctional periods in the Senate’s entire history.

For the moment, Senate Republicans have some leverage to drive a hard bargain on the power-sharing agreement: Until a new resolution is worked out, the GOP will retain its existing majorities on Senate committees.

But the GOP only has such leverage for as long as Democrats allow them to. The Senate is governed by a dizzying mess of procedural precedents. But as a constitutional matter, Senate majorities are sovereign over the body’s internal affairs. Chuck Schumer’s caucus has the power to simply rewrite all of the Senate’s rules on a party-line basis, whenever it wants. They are just reluctant to do so.

Fortunately, for the moment, Senate Democrats seem even more reluctant to forfeit their “nuclear option.” The constituencies holding IOUs should make sure that they stay that way — and, when the moment’s right, press the big red button.