Less than a decade ago, Mitt Romney campaigned for the presidency on a promise to stop the government from giving “free stuff” to poor people. The 2012 Republican nominee was so adamant in his opposition to welfare spending, he told his supporters to remind their pro-Obamacare friends that “if they want more stuff from government, tell them to go vote for the other guy — more free stuff. But don’t forget nothing is really free.” Romney reiterated his contempt for government programs that help non-affluent people survive in his infamous “47 percent” speech, in which he declared that a near-majority of Americans “believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it” — and would, therefore, never vote for him.

Nine long years later, Romney is calling for the passage of the most generous cash-welfare program in modern U.S. history.

On Thursday, the Utah senator introduced the Family Security Act, a bill that would provide all non-rich households in the United States with $350 a month for every child they are raising who is younger than 5 years old, and $250 a month for every child between the ages of 6 and 17, up to a maximum of $1,250 a month. In addition to these benefits, new parents would collect a $1,400 payment just before their child’s birth.

Put differently: If Romney’s bill passes, then the parents of a child born next year will receive $62,600 in child support from Uncle Sam by the time that kid turns 18.

Crucially, unlike every other child-welfare policy that the United States has entertained in the past quarter century, Romney’s plan would not give less help to the very poorest children in America, so as to punish their parents for not working. And unlike the refundable child tax credit, the benefits in Romney’s plan aren’t delivered in a lump-sum rebate to the subset of low-income families who properly file for it, but rather, to all non-affluent parents in monthly installments, administered by the Social Security Administration (the allowance phases out starting with single parents whose incomes exceed $200,000, and joint filers with incomes above $400,000). This mode of administration enhances the policy’s utility to families who can’t wait until the end of the year to make ends meet, while also ensuring damn-near 100 percent participation in the program. That last bit is crucial: As is, roughly 22 percent of those eligible for the child tax credit do not receive it.

So what’s the catch?

Generally speaking, when a conservative serves up a good-looking policy, there’s a bottle’s worth of poison pills buried inside (see: Charles Murray’s proposal to establish a universal basic income … by liquidating the welfare state). And at first glance, Romney’s plan appears to be no exception: The Utah senator’s policy is funded primarily by cuts to other programs and tax credits that aid the poor. But these pay-fors are more benign than one might fear.

Romney’s bill would eliminate the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) and the Head of Household (HoH) tax-filing status, while reducing the value of the EITC to workers with children, and ending federal funding for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

The child allowance makes the CDCTC largely redundant. And the same can be said of the HoH, which has a deeply regressive policy design (the poor derive no tax relief from the policy, and the more a worker earns, the more tax relief he or she receives). These realities, combined with the sheer size of the child benefit in Romney’s plan, means that swapping out these tax benefits for the child allowance is a good trade for just about all U.S. families.

The elimination of federal block grant for TANF would be concerning — if TANF had not already been gutted. As Matt Bruenig of the People’s Policy Project explains:

In 1997, the federal government allocated $16.5 billion to this block grant program. In 2019, it allocated the exact same amount of money, which was worth 40 percent less than in 1997 in inflation-adjusted terms. Over that same period, the share of TANF block grants that went out as cash assistance to poor families with children declined from 71 percent to 21 percent. Taken together, this means that federal spending on TANF cash assistance has fallen by 82 percent since 1997. In 2019, it was only $3.5 billion. For comparison, food stamp benefits in 2019 totaled $55 billion.

To be sure, $3.5 billion in federal support to needy families is much better than zero. But the Romney plan’s total benefit to such families would dwarf that sum.

The biggest problem with Romney’s pay-for scheme is that its revision to the EITC would leave a very small subset of working-class families worse off. For example, a single mother of one — who is eligible for the maximum EITC benefit under current law, and whose child is over 5 years old — would take home $1,420 less under Romney’s plan, according to the People’s Policy Project. But the number of people in this situation, or an analogous one, would not be large.

Finally, in addition to its cuts to various forms of aid to low-income families, Romney would also eliminate the state-and-local tax (SALT) deduction, a policy that delivers the vast majority of its benefits to upper-income households. There is a plausible progressive defense of the deduction on political grounds: SALT makes it a bit easier for Democrats to advance social democratic policies at the state level by effectively enabling blue states to finance a portion of their welfare programs through deficit spending (if you raise taxes on your rich residents — who then get to write some of those taxes off on their federal returns — you’ve essentially tapped Uncle Sam’s sweet sweet money printer).

Nevertheless, if the choice before Congress were Romney’s plan or the status quo, there’s no question the former would leave the nation as a whole better off. To put that point more concretely, according to an analysis from the Niskanen Center, Romney’s policy would lift 5.1 million Americans out of poverty, and slash the child poverty rate by one-third.

Romney’s plan is better than Biden’s (for now).

As part of his pending $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, Joe Biden has proposed a fully refundable child tax credit. The president’s policy would provide $3,600 a year (or $300 per month) to parents of kids under 6, and $3,000 a year (or $250 a month) to parents of kids ages 6 to 16.

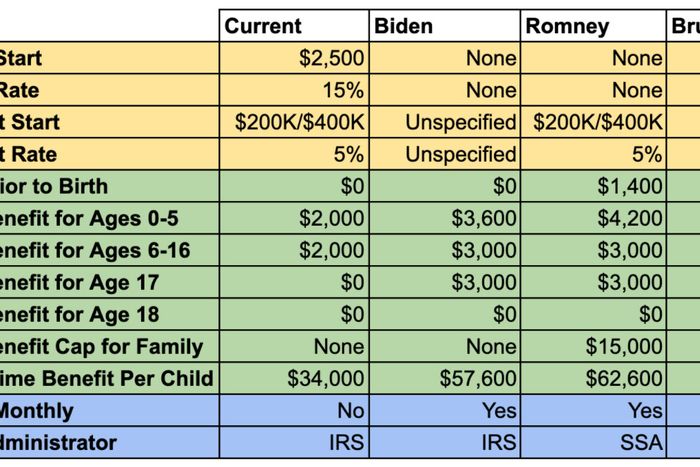

In other words: It provides less overall benefit than Romney’s plan, as Bruenig helpfully illustrates in this table (which also contrasts the two plans with the current child tax credit and his own ideal program):

Biden’s plan does have a clear advantage over Romney’s: It does not involve cutting any other existing welfare or tax benefits. On the other hand, Biden’s policy, as currently written, expires after a single year. And that vice is bound up with the program’s virtue: As a temporary, COVID-era measure, the child tax credit expansion requires no offsetting pay-for; there is broad support in Congress for deficit spending in a context of high unemployment. In order to make the new child tax credit permanent however, some offsetting tax hike or spending cut will likely be required. This is because — unless Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema, and other moderate Democrats suddenly embrace filibuster abolition — the Biden plan would need to be implemented through the budget reconciliation process (which requires all new spending to be fully offset after ten years) or else with the support of ten Republican senators (who would surely insist on paying for the policy with cuts to other welfare programs).

All of which is to say: If Congress were given a choice between Biden’s single-year child tax credit (with no cuts to other welfare programs), and Romney’s permanent child allowance (with its specified cuts to other welfare programs), the latter would leave the nation better off.

Alas, Marco Rubio and Mike Lee want to punish the poorest kids in America for having unemployed parents.

In a statement Thursday night, the two GOP senators most sympathetic to a child tax credit expansion, Mike Lee and Marco Rubio, both decried Romney’s proposal as “welfare assistance” that would undercut “the responsibility of parents to work to provide for their families.” In other words: While the senators are supportive of a large increase in government aid to children, they will only do so if the policy provides little to no aid to the very poorest kids in the country, so as to teach their parents a hard lesson about the importance of work.

This concern for welfare disincentivizing work may sound reasonable, especially if you were exposed to Econ 101 at an impressionable age. But it is a dumb and malicious bit of dogma. The theory has some plausibility in a context where there are steep cliffs in eligibility for government aid, such that taking a few more hours from your employer would cost you access to Medicaid or a housing benefit or what have you. But under Romney’s plan, no low-income worker would lose their child allowance by accepting a higher-paying job. The benefit is all but universal. Almost all advanced democracies offer such universal, unconditional child aid; none have suffered an economically devastating surge in voluntary unemployment as a result. And even if it somehow were the case that a child allowance disincentivized work, the U.S. economy does not supply enough jobs for all who are actively seeking employment. At the peak of the last expansion, 3.5 percent of workers looking for jobs still could not find them. Conditioning aid to children on parental employment — while allowing millions of workers to be locked out of the labor market — is an act of mindless cruelty. America has already wronged the unemployed by failing to build an economy that makes use of their talents and energies. Lee and Rubio are effectively insisting on punishing these people for their involuntary exclusion from the labor force by condemning their kids to poverty. This is a de facto form of mass child abuse, which has lifelong consequences for those who suffer it; research shows that giving cash assistance to needy parents improves their children’s health, test scores, educational attainment, and future employment prospects; which is to say, it promotes work.

We’re not in Reaganland anymore.

Lee and Rubio have made clear that Democrats cannot pass Romney’s child allowance on a bipartisan basis; there will not be ten GOP votes in the Senate for a child aid program that doesn’t punish the poor. Fortunately, Democrats have already initiated the budget reconciliation process, which empowers them to pass legislation out of the Senate on a party-line vote. Reversing a small portion of Donald Trump’s tax cuts for the rich would be sufficient to cover the cost of Romney’s program. Democrats should just take the good parts of the Utah senator’s proposal, and ditch its imperfect funding mechanism.

Wherever the child allowance debate goes from here, it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on how far it’s already moved. Twenty-five years ago, a Democratic president effectively made slashing aid to poor families a cornerstone of his domestic agenda. Today, a Republican from one of the reddest states in the country is fighting to give tens of thousands of dollars to every poor family, dispensed in monthly increments for the full length of their kids’ childhoods.

Romney’s proposal didn’t come out of nowhere. Progressive Democrats and policy wonks have been making the case for child welfare, and drafting model legislation to deliver it, for years. The COVID crisis then created a political opening for new social transfers: The CARES Act’s $1,200 survival payments shattered the taboo against direct, unconditional cash assistance that had developed following the Reaganite backlash to the welfare state. Those “COVID stimulus checks” alerted the American people to their government’s capacity to help them — and America’s political class, to the electoral benefits of putting cash in their constituents’ hands.

With any luck, the passage of child allowance will teach our polity similar lessons in the power of solidaristic politics to ease our collective burdens. And then maybe, just maybe, no Republican presidential nominee will ever again feel compelled to advertise his contempt for those who receive “free stuff” from the government.