This week, the San Francisco Chronicle reported on findings that confirm the city’s Black, Asian American, and Latino children are suffering enormous academic setbacks by relying on remote learning. Presented with this harrowing data, the city’s school school-board president, Gabriela Lopez, blithely waved it off. “They are learning more about their families and their cultures, spending more time with each other,” Lopez told the Chronicle. “They’re just having different learning experiences than the ones we currently measure, and the loss is a comparison to a time when we were in a different space.” It’s just a different kind of educational experience, you see, no better or worse.

If you are a parent of one of these children, you might see it more starkly. The “learning experiences” that we “currently measure” are the teaching of skills like reading, writing, and math. The “different learning experiences” children are getting instead are not just different but — at the risk of making a nonrelativistic judgment — worse.

Lopez’s quote circulated on Twitter, and I saw several journalists expressing bewilderment over where she was coming from and why she would say something so peculiar. The answer is that the education left has found itself in the position of defending the interests of its employees rather than its students. The increasingly fashionable solution it has found to the problems posed by the pandemic is to dismiss the importance of education altogether, and to assert that the only factor schools need consider is the health and welfare of their teachers.

I wrote last month about how the education-reform wars have forced teachers unions and their allies to minimize quality of education itself as a mere by-product of larger forces. “The biggest correlation in education is between poverty and test scores,” anti-reform guru Diane Ravitch has said. “If you think the test scores are too low, go to the root causes.” Better-designed schools can’t serve any purpose because only eradicating poverty can do anything for poor kids.

The conflict over reopening schools during the pandemic has brought this tension into higher relief. High-performing charter schools are a lifeline for poor urban kids, but they serve just a small proportion of American public-school students. School closing are a mass issue that has brought the dissonance between the interests of teachers unions and those of students to the doorsteps of American families never before affected by the education-reform debate.

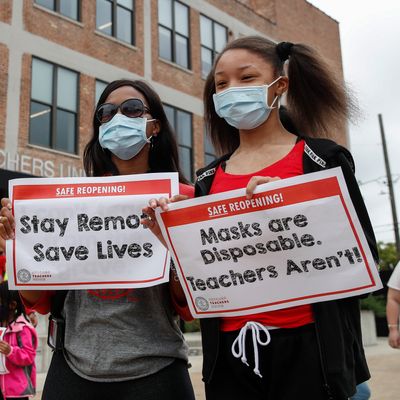

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officially declared that the “preponderance of available evidence” suggests in-person schooling creates only a modest risk of COVID-19 spread and should be resumed with appropriate precautions. But to call for schools to open hardly makes it so. School systems across the country are now battling their teachers unions to force them to go along. In Washington, D.C., the city first had to win an arbitration ruling that the schools were mostly safe and then had to ask a judge to stop the union from planning a strike. Legal fights like this are breaking out across the country.

The teachers’ position is deeply sympathetic. They are being forced to bear a mortal health risk — perhaps a small one, but terrifying nonetheless. Like people who own restaurants or bars, they are being asked to make a dear personal sacrifice for the public good (in the case of restaurant owners, by shutting down and likely losing their business; in the case of teachers, by coming to school).

The teachers unions and their defenders have tried to defend their stance by maintaining that the risk of spreading COVID in schools is greater (or, at least, more uncertain) than experts say. From a societal standpoint, though, it doesn’t matter much whether the risk is small or negligible because the damage caused by not reopening — children forfeiting a year or more of in-person school — is staggering. The social and economic toll of the learning loss will be borne for decades to come. That is why some supporters of the union position are trying to escape the vise by discounting the importance of educating children.

Jacobin’s Joshua Mound made this case in a column arguing against making any effort to reopen schools:

No matter that the odds facing children [in poverty] are steep, that returns to education aren’t driving inequality, that the proportion of people in poverty with high school and college degrees is rising, or that people without a high school or college diploma deserve a living wage. For reformers, it doesn’t matter that fixing education won’t end poverty or that increases in equality tend to increase educational attainment, not the other way around.

Why bother bringing low-income kids back to school, when the only thing that can help them is smashing neoliberalism?

A different strand of this argument comes from Ibram Kendi, who has explained his position in an article headlined “Why the Academic Achievement Gap Is a Racist Idea” and in his book “How to Be an Anti-Racist.” Kendi’s argument is that data showing that Black students have learned less than white ones does not show that Black students have received a worse education from their schools. Rather, it shows that the tests themselves are biased:

What if different environments actually cause different kinds of achievement rather than different levels of achievement? What if the intellect of a poor, low testing Black child in a poor Black school is different — and not inferior — to the intellect of a rich, high-testing White child in a rich White school?

Of course, the existence of an achievement gap does not demonstrate any innate difference in potential between Black and white children, only that the former have been given less of a chance to develop their abilities. But Kendi’s argument, by denying the existence of an achievement gap, by the same token denies the need to improve the quality of education provided to minority children.

Mound’s Marxian economic version and Kendi’s left-wing “anti-racist” version both wind up in the same place: Trying to improve schools for low-income minorities is impossible or pointless. Therefore, the primary equity at stake in public education is the labor rights of the workforce. The dilemma of forcing the left to admit it’s choosing teachers over educating poor kids is resolved because we have crossed out one half of the equation. There’s no such thing as good schools or bad schools. Just different schools.