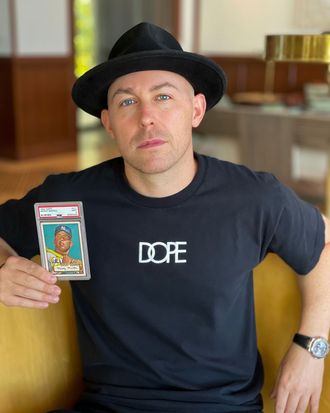

This time last year, the only sports cards Rob Gough owned were the ones he’d collected as a kid. Somewhere in his possession are plastic sheets filled with Michael Jordans, Shaquille O’Neals, and assorted members of the 1990s Cincinnati Reds, all mass-produced and worth roughly the cardboard they were printed on. These days, Gough’s collection looks a bit different. The entrepreneur says that by mid-January of this year, he had spent $10 million on various trading cards, a spree that culminated with his biggest purchase yet: $5.2 million for a 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle in nearly perfect condition. With that, he shattered the record for the price of a single card.

It was a jaw-dropping purchase but hardly an isolated event in a suddenly torrid sports-card market. The previous record for the priciest sale ever had been set just months before, in August 2020, when a one-of-a-kind 2009 Mike Trout baseball card sold for $3.936 million — a massive jump from the $400,000 it went for in 2018. In September, a Giannis Antetokounmpo card sold for $1.812 million (a record for a basketball card), and earlier this year, one of Patrick Mahomes sold for $861,000 (setting a record for football). On eBay, overall domestic sales for trading cards were up 142 percent in 2020.

“I’m not sure I’ve ever seen anything like this in my career,” says Jeff Rosenberg, the president and CEO of Tristar Productions, a Houston-based memorabilia company that promotes collectible shows.

Some of the increased interest in trading cards can be attributed to onetime collectors rediscovering their childhood hobby during the pandemic, as people stuck at home direct their disposable income to a sentimental pastime. But another trend, which had already begun before last March, has helped drive the headline-grabbing, six- and seven-figure purchases.

Historically, the collectors who buy up rare baseball cards have been driven by emotion; the cards’ investment potential was secondary to what Rosenberg calls the “visceral experience” of owning them. Now, he says, that calculus is starting to flip, and cards are increasingly being seen as investments first. “Over the last several years,” Rosenberg says, “I’ve seen a bunch of younger folks come in. And some of them like the cards. [To] others, it’s really a strategic asset. These cards to them are no different than a stock portfolio.”

Indeed, Gough says his purchase of the Mantle card had more to do with profit-making than it did fandom.

“I would say 70 percent investment, 30 percent from an emotional standpoint,” he says. “I think this card is going to continuously beat the S&P 500. So what am I gonna do? Take the $5.2 million and put it in the market? Put it in a house, where you’re going to get 3 to 8 percent a year? Or put it in Mickey Mantle?”

Ken Goldin, the founder and executive chairman of Goldin Auctions, which has handled the sale of many high-end cards, says he’s also seen a rise in younger buyers over the past several years. His explanation: Millennials and Gen-Zers who come into money “may not want to purchase stocks and may not want to purchase art, and they’re looking for a nontraditional asset that they enjoy.”

But according to Goldin, it’s not just individual buyers swiping up the top cards. He says sports collectible funds have formed with the sole purpose of buying and sitting on valuable trading cards, while some existing alternative investment funds now allocate a portion of their portfolios to trading cards.

This isn’t the first boom for the higher end of the industry. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, sale prices for rarities like the Honus Wagner T206 — long considered the holy grail of baseball cards — alerted the general public that the cards they collected and quite possibly threw away as kids could have real value. Card companies responded to the increased interest by overproducing their sets, rendering most of their output from the era more or less worthless. Ken Griffey Jr.’s 1989 Upper Deck rookie card, once the hottest card in the hobby, famously turned out to not be very rare at all: The company is estimated to have produced more than 2 million of them. (One Kansas man owns hundreds.)

Card-makers eventually started to build artificial scarcity into their products: Some are produced in extremely small quantities; in some cases, just one of a card may be made. Now the most sought after of these cards — in the right condition, as determined by an independent evaluator — are suddenly selling for as much as the most iconic ones of yesteryear.

All of this lends itself especially well to the investor mind-set. Mickey Mantle’s place in history is well established, but a younger player like Antetokounmpo could still see his stock rise down the road. Buying his card now is a bet that he’ll remain a star for many years, that his cards will remain sought after, and that they’ll sell for a higher price later. That these modern cards can be even scarcer than the vintage ones — there’s only one of the record-setting Antetokounmpo, for instance, compared to nine 1952 Topps Mantles graded at least as high as Gough’s by the authenticator PSA — only adds to the appeal as a rare asset.

“For the first time, perhaps in history, sports collectibles are sort of a cool thing to do,” says Ezra Levine, the CEO of Collectable, a fractional ownership platform that lets users buy and sell shares in valuable cards. “You have athletes and influencers and celebrities who are into the hobby. You have mainstream media outlets getting into it.”

Just last week, Goldin Auctions announced it had raised $40 million in funding from the Chernin Group, in a funding round that included notables like Mark Cuban, Kevin Durant, Logan Paul, Mark Wahlberg, and Deshaun Watson.

Even those rooting for prices to continue rising indefinitely concede that certain aspects of the hobby are bound to cool off: the demand for less-scarce modern basketball cards, for instance, or the hype around athletes who play above their usual level for a couple of weeks and see their card values spike. But they say they’re confident the “Willy Wonka golden ticket cards,” as Goldin calls them, will continue to increase in value over time.

“It depends what your time horizon is,” says Rosenberg. “Will prices ebb and flow? Yes. At some point, the pressure will change. But what do I see in the near term? There’s still more people who are finding out about this and buying.”