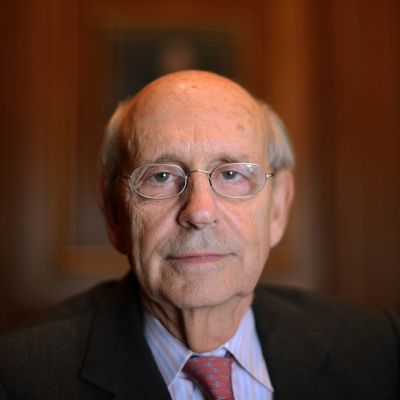

After Donald Trump managed to appoint three Supreme Court justices in just four years, liberals are on the judicial backfoot and trying to regain their composure. One of the first orders of business is to avoid a repeat of strategic missteps that have allowed Republicans to shape the Court in their image. With that in mind, the conversation has turned to the future of Justice Stephen Breyer. I spoke with senior correspondent Irin Carmon and political columnist Ed Kilgore about what Breyer might do — or not do — in the next two years.

Ben: Ruth Bader Ginsburg chose not to retire in 2013, when a Democratic Senate could have confirmed a younger justice to take her seat. Seven years later, President Trump’s pick, Amy Coney Barrett, replaced her instead. Democrats definitely don’t want this scenario to repeat itself in case a Republican wins the presidency 2024 — or even if the GOP takes back the Senate in 2022, which could mean they’d blockade any Biden nominee. So there’s already been talk of the possibility that Stephen Breyer, the oldest of the three liberals on the court at 82, might take one for the team, so to speak, and call it quits in the next year or two. Do you think this is going to happen?

Ed: I have no inside knowledge of Breyer’s intentions, but the pressure on him is going to get really intense during the course of this year.

Irin: I have attempted to learn of Breyer’s intentions for my last two pieces on the Court — on the prospect of him being replaced by the first Black woman on the Supreme Court, as promised by Biden, and on Justice Sotomayor seemingly poised to take over as the most senior liberal if he does step down. I wasn’t able to learn much, but it is striking how much less subtle the pressure is on him than it was during the Obama administration.

Ed: Aside from the possibility of missing the opportunity to replace a justice, Democrats would like to get a replacement onto the Court who can serve for another 30 years or so.

Irin: The Ginsburg cautionary tale is one reason. But there’s also a much more concerted effort, intensified by her death, among liberals to be more strategic on the courts. There was even an open letter from the progressive group Demand Justice, which didn’t exist during the Obama administration, demanding Breyer step down. Breyer worked in judicial politics, so he shouldn’t have to be told how this works. But he didn’t sound particularly urgent when he told Dahlia Lithwick, “Eventually I’ll retire, sure I will. And it’s hard to know exactly when.”

Ed: This could be a matter of a justice losing control over the general length of his career taking solace in control over the exact timing. Anthony Kennedy sure played that game and was able to spring a surprise when he did retire.

Ben: The Supreme Court works in mysterious ways, and the justices often style themselves as above politics, even if they’re most certainly not. If there were a pressure campaign under way from elected officials — as opposed to only advocacy groups — what would it look like? Do you think anyone would actually have the audacity to not-so-subtly suggest to Breyer himself that he should maybe call it a day?

Irin: Would someone set up a Zoom to tell Breyer to hang up the robe? I don’t think so. When RBG died, the Times reported that during the Obama administration, Walter Dellinger suggested sending Breyer to France as ambassador. Breyer later mockingly brought it up to him if I recall correctly. The Times also said Obama was too reticent to raise anything with RBG directly over lunch.

Ed: I’d say that publicly asking Breyer to retire would be an easy way for any Democratic pol thought to be vulnerable to a progressive primary challenge — or who wanted to run for president — to stand out. Your basic White House–mad senator isn’t going to lose much sleep over Breyer’s sensitivities or the arcane etiquette of the legal profession.

Irin: Yeah, the question is if it backfires, though. These justices have fragile egos.

Ed: I didn’t say it would necessarily work — just that I’d be surprised if someone didn’t try it. SCOTUS traditions have been falling pretty regularly for a while now.

Ben: To Irin’s earlier point — it’s acknowledged by pretty much everyone that Republicans have outmaneuvered Democrats on the courts for decades now. The party has a whole industrial-strength machine set up to usher young conservatives from law schools to the federal bench. And the makeup of the Supreme Court, and even lower courts, is an issue conservative voters have tended to care a lot about in a specific way, much more so than Democrats. Do you feel this balance shifting in the aftermath of the Merrick Garland debacle and with a truly conservative majority on the Court that might strike down Roe v. Wade and other bedrock laws?

Ed: I don’t know if anything short of a catastrophe will convince Democrats to care as much about the courts as Republicans, but the dynamics are clearly, finally shifting.

Irin: I think Merrick Garland had started to shift the terms of the debate. Here was a solidly centrist pick, a white guy that Republicans had said nice things about, not even given a chance at a vote. That radicalized liberal elites who might have prized the notion of a depoliticized judiciary. But the sense that Mitch and Trump stole RBG’s seat is something that got the grassroots’ attention. Look at the massive Senate fundraising that followed her death.

Ed: Yes. RBG’s death definitely felt like the end of an era, and the fact that Trump and the GOP rushed through the most ideological candidate available (unveiled at a COVID-19 superspreader event) was shocking, if predictable.

Irin: It’s also been interesting to see the Biden administration be so responsive on the courts after widespread consensus that Obama ignored them (early on) at Democrats’ peril. The choice of Ron Klain as chief of staff is significant. No one in Democratic politics is more experienced in the nominations process. The American Constitution Society may not be a well-oiled machine like the Federalist Society, but Ron was a board member and a regular at the conferences.

And it’s not just paying attention to the courts; they’ve even been responsive to the idea that more public defenders and civil-rights attorneys should be on the Court and not just corporate law partners and prosecutors.

Ed: Well, it probably didn’t pass unnoticed in Biden circles that Donald Trump built a fiercely loyal constituency via close attention to judicial appointments.

Ben: After RBG’s death, there was a big push for Democrats to pack the Court in response to the unfairness of the Trump years. But with Dems barely squeaking out a Senate majority, that dream is dead, at least for now. Do you think there’s any chance of it being revived in the near term? Say, if this Court strikes down Roe and then Democrats pick up a couple Senate seats in 2022?

Irin: Even when some Democrats were dreaming of expanding the Court, there was never full Biden buy-in. He did agree to put together a bipartisan commission, which arguably is what politicians do to help ideas die. Schumer has floated the expansion of the (overworked) lower courts, which would be a great idea. But big picture, that wouldn’t solve much if 5-6 conservative justices keep hacking away at Roe and Casey.

Ed: It would be interesting (in a bad way) to see what would happen if there’s a calamity like a direct assault on Roe. I suspect it would be easier to get a filibuster reform that would make it possible to codify Roe as a matter of federal policy than to radically change the Court.

Irin: I agree with Ed. There have been several attempts to codify Roe, or at least limit states’ ability to ban abortion, at the federal level, and there could be more in the future depending on how the Supreme Court acts.

Ed: It wouldn’t be that big a reach to make legislation on constitutional matters exempt from the filibuster just like judicial nominations. Republicans would still fight it like hell, but if it happened soon, Collins and Murkowski might play ball.