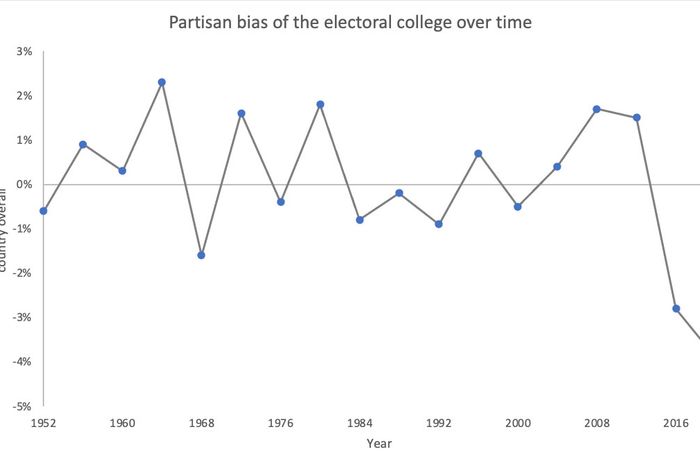

The Republican Party has won the popular vote in just one of the six presidential elections held this century — but has nevertheless held the White House for 12 of the past 20 years. Since 2000, the GOP’s Senate caucus has never represented more voters than their Democratic colleagues. Yet Republicans have controlled the upper chamber for more than half of the past two decades. Meanwhile, for the entirety of this millennium, the median House district has been at least 2 points more Republican than the nation as whole; for most of the past decade, the House map has had a pro-GOP bias of more than 4 percent.

The GOP’s capacity to wield power in excess of its popular support has had profound implications for American political life. Were the U.S. president elected by popular vote, and Congress governed by proportional representation, the GOP would never have held unified federal power this century, and a liberal majority would reign over the Supreme Court. Put differently: Under a more democratic system of representation — in which every American’s partisan preference counted equally, irrespective of where he or she lived — the GOP would have either been locked out of power for the past three decades, or else forced to moderate its agenda, as governing in defiance of the popular will wouldn’t have been an option.

As is, the Republicans’ growing dominance in rural areas, which are structurally overrepresented at every level of government, has made the party less reliant on majoritarian approval than ever before: Had Donald Trump lost the two-way popular vote by “only” 3.9 percent in 2020, he would very likely have won reelection. Meanwhile, the median U.S. state is nearly 7 points more Republican than the nation as a whole, giving the GOP an overwhelming advantage in the race for Senate control. Finally, the House map’s pro-GOP bias is set to increase after the next round of redistricting — if Congress doesn’t pass a law forbidding partisan gerrymandering in federal races before new districts are drawn.

All of this makes the structural biases of America’s political institutions immensely valuable to the conservative movement. But it also makes those biases difficult for conservatives to defend. The notion that the winning presidential candidate should be the one who got the most votes, or that gerrymandering is wrong, is intuitive to the American public. As of last year, more than 60 percent of U.S. voters supported the abolition of the Electoral College, while an even larger majority favors nonpartisan congressional districting.

The GOP’s resident sophists have mustered a variety of rationalizations for defying the public’s desire for popular democracy. Many of these are fallacious but facially benign (e.g., the Electoral College does not actually require presidential candidates to appeal to a diverse array of the nation’s regions, but there is nothing inherently sinister about wanting presidential candidates to do that). More often though, conservatives find themselves dusting off Jim Crow–era arguments for privileging “states’ rights” over equal citizenship, and/or insisting that (predominantly white) rural-dwelling Americans are more American than city-dwellers, and therefore deserving of disproportionate political power.

Following House Democrats’ recent passage of a H.R.1, package of voting and campaign-finance reforms, the right’s apologias for minority rule have attained new heights of audacity. On Tuesday, a pair of op-eds in National Review and the Wall Street Journal decried the Democrats’ proposals for increasing voter participation and mandating nonpartisan redistricting as a “partisan assault on democracy” and “brazen attempt to rig the game for a permanent Democratic majority.”

In the Journal, Kimberley Strassel accuses Democrats of “selling out their own states” (by making it harder for those states to disenfranchise the people who live in them). As she writes:

The bill would strip states of their authority to decide methods of balloting, election deadlines and most aspects of election security. It would mandate mail-in voting, impose registration rules, dictate ballot-return dates, and void identification standards. It even limits states’ ability to draw congressional districts.

Here are her arguments for why the right of states to restrict ballot access and draw partisan congressional districts should take precedence over voting rights and equal representation:

• Election rules should be dictated by state and local officials because they are “closest to the people, elected by the people, most responsive to the people.”

• It might not be constitutional for the House to legislate the rules of state elections.

• Many voters lack faith in the validity of the 2020 results, and states must therefore be allowed to enact the voting reforms that restore public confidence in elections.

• And finally, the Democrats’ bill is really a “brazen attempt to rig the game for a permanent Democratic majority,” and “the proof is the fury with which the left is demanding the Senate kill the filibuster to pass H.R.1 with 51 votes, including the vice president’s tiebreaker.”

These are not strong arguments.

The notion that state governments are closest to “the people” is wrong in two respects. First, in the 21st century, it simply is not the case that local officials are more accountable to their own constituents than federal ones are. The collapse of local journalism and nationalization of all politics has left the median voter grossly ignorant of state government. Surveys suggest that Americans are significantly more likely to know the name of their House representative than they are the name of their state legislator. The vast majority of voters choose state legislators based on the candidates’ partisan affiliation, and choose their own partisan affiliations on the basis of national political events. For these reasons, the typical state legislator is primarily accountable to the tiny subset of donors, activists, and interest groups that scrutinize statehouse developments, and/or participate in state legislative primaries.

But the bigger problem with Strassel’s argument is that almost all state legislatures are unrepresentative of their electorates as a result of the very anti-democratic redistricting practices that Congress is trying to prohibit. For example, in Wisconsin’s 2018 midterm election, the Democratic Party’s candidates won 53 percent of all votes cast for the state assembly, but due to gerrymandering and Democrats’ urban clustering, this vote share gave the party just 36 percent of the state assembly’s seats.

The Republican supermajority in Wisconsin’s legislature proceeded to strip the incoming Democratic governor of a variety of powers, effectively transferring authority away from the branch of government elected by the state’s Democratic majority and toward the one elected by its Republican minority.

In justifying these measures, Wisconsin Republicans invoked arguments nearly identical to Strassel’s: They argued that “state legislators are the closest to those we represent” — but unlike Strassel, the Badger State reactionaries were forthright about their belief that city-dwellers are unworthy of full citizenship. “If you took Madison and Milwaukee out of the state election formula, we would have a clear majority,” Wisconsin State Assembly Speaker Robin Vos explained. “We would have all five constitutional officers and we would probably have many more seats in the Legislature.”

Strassel’s constitutional argument may be her most laughable. She writes, “Article I gives state legislatures the authority to prescribe the ‘times, places and manner’ of holding congressional elections.”

Here is the section of the Constitution Strassel is quoting:

The times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators. [Emphasis mine.]

Strassel’s claim that Democrats are preventing states from restoring faith in elections through voting restrictions is a tad less stupid, but much more sinister. As many Republican senators have admitted, the proximate cause of voter distrust in the 2020 election was not actual malfeasance, but the GOP nominee’s decision to make baseless allegations of malfeasance. No restriction on ballot access can prevent a Republican nominee from telling similar fibs in 2024. And nothing except a Republican victory that year will prevent some GOP voters from regarding the election as illegitimate. To the extent that Republican state legislatures are trying to restore faith in elections through their voting “reforms,” they are trying to do so by preventing Democrats from winning elections.

Georgia Republicans just made this reality plain. On Tuesday, the Peach State’s Republican-held Senate passed a package of voting laws that, among other things, aims to suppress Black voter participation by restricting early voting on Sundays, when African-American churches have historically led their congregations to their precincts in a tradition known as “souls to the polls.” Republican state senator Jason Anavitarte argued that such voting restrictions were necessary “to make sure all Georgians trust the [election] process.”

Finally, Strassel’s notion that H.R.1 is a plan to establish a permanent Democratic majority — as evidenced by liberals’ advocacy for abolishing the Senate filibuster — is incoherent. You don’t need to believe that Democrats will control the federal government forever to believe that Senate majorities should be allowed to pass laws. Most of the progressive commentators who are currently calling for the filibuster’s abolition were already doing so back when Republicans controlled all three branches of government (I myself published a case for ending the legislative filibuster in April 2017). What’s more, even if Democrats abolished the filibuster, in order to grant statehood to D.C., Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Island, the Senate would still be biased in the GOP’s favor.

Similarly, because Democratic voters are heavily concentrated in urban centers, a House map drawn entirely by nonpartisan commissions would still likely favor the Republicans. If making it easier for Americans to vote – and the House and Senate, only slightly biased in the GOP’s favor – is enough to render the Republican Party a permanent minority, then the problem would seem to be with the conservative agenda, not the Democrats’ election reforms.

National Review’s diatribe against H.R. 1 is a bit more sophisticated. The magazine’s editorial board demonstrates greater fluency in the legislation’s fine details than Strassel does, and they raise concerns about the bill’s campaign-finance provisions that I am not prepared to adjudicate at present. But in making its case against nonpartisan redistricting and federal voting rights laws in 2021, the flagship journal of American conservatism displays about as much intellectual rigor and respect for democracy as it did when making the case for white-supremacist rule in 1957.

Like Strassel, National Review defends the sacred right of states to customize election laws to fit local tastes. Unlike the Journal columnist, the magazine goes out of its way to draw attention to the ugly history of its own argument, defending the principle that states should have supreme authority over voting rules on the grounds that this has served America well for hundreds of years. The editorial board warns that H.R. 1 would “end two centuries of state power to draw congressional districts,” as though southern states have not spent the bulk of that time using their authority over districting to dilute the influence of nonwhite voters. It proceeds to assert that states “have long experience running elections, and different states have taken different approaches suited to their own locales and populations.” Again, the magazine fails to note, even parenthetically, that states specifically have “long experience” at tailoring voting to their local “populations” by disenfranchising disfavored segments of those populations. This is not an academic point for reasons already discussed: In several key swing states, Republicans have secured all-but permanent control over state legislatures through partisan gerrymandering, and routinely use this control to defy and disempower multiracial Democratic majorities in those states.

The magazine proceeds to make its desire to suppress the political participation and influence of Democratic-leaning constituencies explicit, lamenting:

The bill shifts the job of signing up young voters to the federal government, which will pay to teach twelfth graders how to register, create a “Campus Vote Coordinator” position on college campuses, and award grants to colleges for “demonstrated excellence in registering students to vote.”

The horror!

But the most telling (and odious) passage of the editorial may be this:

Restrictions on felon voting in federal elections in many states are overridden [by the bill] … It also counts inmates as residents of their last address (even if serving a life sentence), a provision aimed at reducing the representation of rural areas where prisons are located.

Here, National Review suggests that the formerly incarcerated should not necessarily have voting rights, but rural areas should be allowed to inflate their representation in Congress by counting the prisoners they warehouse as residents. The magazine does not offer any justification for the latter proposition. And it is difficult to comprehend what its rationale could possibly be.

The logic behind apportioning representation on the basis of an area’s total population, rather than its voting-eligible population, has always been that (1) an area’s children and disenfranchised adults deserve some political consideration, and (2) these groups likely have some interests in common with their voting-eligible parents and neighbors, and thus, (3) an area’s voters can be trusted to represent at least some of the interests of its broader population.

Which raises the question: Does National Review believe that the interests of the incarcerated are better represented by voters in communities where they’ve never lived as free people (and where prisons are major sources of employment) than by their own kin in the communities they came from? If not, why precisely should rural areas be allowed to inflate their congressional representation by pretending that their members of Congress will meaningfully represent the interests of disenfranchised people caged in their districts?

There is no coherent answer to this question except the honest one: Rural areas with prisons in them tend to vote Republican, and all election laws that currently inflate the Republican Party’s power are just by definition.

In truth, conservative opponents of federal election reform are not trying to protect democracy from the threat of “authoritarian power grabs”; they are trying to protect their own party’s authoritarian power grabs from the threat of democracy.