This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Michael Osterholm has spent the past year as afraid of getting Covid as anyone else. “You know how many times I’ve woken up in the morning and said, I wonder if today’s the day I could get infected?” One of the world’s leading epidemiologists, he is reassured by the fact that he doesn’t go anywhere—“I’m the guy who has the same tank of gas in his car that he had three months ago”—but he, too, is desperate to be done with the pandemic.

“I miss my grandkids,” he told Intelligencer from his Minneapolis-area home, his assured voice turning wistful. “My God, I miss my grandkids.”

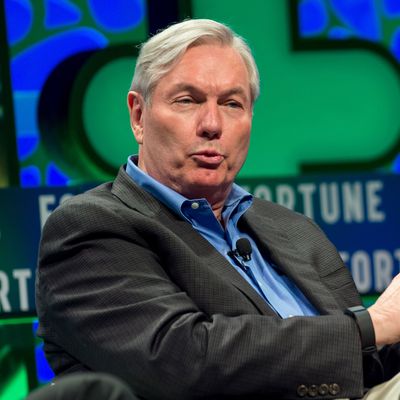

Osterholm, 67, is the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota and has spent the past four decades studying epidemics, but he became nationally famous a year ago for his stark predictions during the first shocking wave of the pandemic in the U.S.

“In April, I said, ‘These are just the foothills. We haven’t even gotten to the mountains yet—and there are big ones coming,’” he recalls. “People, of course, dismissed that as just hyperbole and just scary. Well, you saw what happened.”

His hair-raising, accurate prediction made him something of a Dr. Doom whose expertise was sought after by everyone from CNN to Joe Rogan. Last fall he earned a spot as an adviser for the Biden transition team, where he controversially floated the potential need for a nationwide lockdown.

Now, Osterholm has a new prediction: More virulent variants, particularly B.1.1.7 first identified in the UK, will likely kick off a surge in cases and deaths in the U.S. in a matter of weeks—just as most states lift restrictions. He’s staking his credibility on being right, and potentially his health, by delaying his own second vaccine shot, which he says should be done across the country in order to make more first shots available to as many people as possible, offering some protection before the wave crests yet again.

This question of delaying second doses has sharply divided the health and science community. But on Monday, the CDC’s vaccination advisory board, ACIP, agreed that the data on changing doses is too limited to make new recommendations—and one dose might not be enough to protect against variants, the advisers pointed out.

Cases, hospitalizations, and deaths dropped dramatically after the U.S. reached its highest peak in January, while vaccinations are climbing steadily past 2 million per day. People are beginning to talk about having a normal summer. But before then, Osterholm believes, another surge will pummel the country.

“This big spike that went up and came down, it gives us this false sense of security that somehow, we’re in control. And we’re not,” he said. First of all, viruses are complicated and often tend to come in waves, he said—and we’re at a terrible starting point for another spike.

“Last summer, in July, 70,000 cases a day was a house-on-fire event in this country. Today, we kind of feel like we’ve won, and we’re at 70,000 cases a day,” he said. “We are right now more open to virus transmission than any time since March. Everybody is enjoying this new Covid-19 holiday. Governors have opened up virtually everything.” Yet in the past two weeks, new daily cases have stopped falling.

One major difference since last March are variants of concern. B.1.1.7, for instance, is about 40 to 70 percent more infectious and causes much more severe illness. It likely arrived in the U.S. in November, and now it’s in every state—and it is more than doubling every week. But there’s another big difference this March: extremely safe, effective vaccines that work against these variants. “The challenge we have right now is we have variants versus the vaccine,” Osterholm said—and the battle is also a race against time.

More than 54 million Americans are above the age of 65—the age group where 80 percent of the deaths occur, and the group most likely to develop severe illness that results in hospitalization, straining health care systems. About 41 percent of those 65 and up have been vaccinated so far, but they need to be prioritized even more, Osterholm said: “What we’re trying to do is protect as many lives as possible.”

Osterholm has a gift for making these statistics deeply personal. “Imagine I’m sitting on one side of the table, and I have two doses of vaccine, one in each hand,” he said. “On the other side of the table is my mom and my dad, or my grandpa and my grandma. And they both are over 65, they both have an underlying health condition. And I’m gonna look them in the eye and say, okay, I can give both doses to one of you, or I can give one dose to each of you. What would you like me to do? Wouldn’t you want, particularly with evidence of the protection we have, to protect both of them, and not leave one totally vulnerable?”

There are a couple of different scenarios Osterholm and his colleagues have outlined to maximize vaccinations. For starters, he asked, “why are we giving two doses to people who have already had Covid? We already have compelling data that you get a very good response after the first dose.” Second, he says, the Moderna vaccine trial looked at the effectiveness of two full doses and two half-doses—and the results were the same for both. Why not switch to two half-doses, and get twice as many people vaccinated?

Finally, Osterholm wants to delay second doses of the two-shot Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines for everyone else—but only until after the surge, which he expects to happen over the next two or three months. By then, the U.S. is expected to have enough doses to vaccinate all adults fully.

A single dose of the mRNA vaccines seems to offer at least the same response as the single-dose vaccine from Johnson & Johnson, Osterholm pointed out. “Why would you say it’s okay to approve one and say the other two are problems if you don’t get both doses?” And data from the single Johnson & Johnson shot showed increased protection the more time went on. It’s possible with just one dose of Moderna or Pfizer, “you would likely see the very same increases over time,” he said.

The catch, though, is that the Moderna and Pfizer trials didn’t study what happened when you only get one dose. Although the first dose seemed to offer some protection on its own, that protection was extended and strengthened by the second follow-up dose—a point critics of Osterholm’s school of thought are quick to make. But that is why advocates such as Osterholm argue for delaying, not abolishing, the second dose.

The experts who favor sticking to the vaccination plan that has been proven to work—two doses, spaced three or four weeks apart—say we need to follow the science. But, Osterholm said, that’s exactly what he’s trying to do. “All of that data was collected before anything had to do with the variants. The variants are a brand-new set of data.”

And new research on the effectiveness of the first dose is emerging. “There is sufficient data to support that, at least for the short term, you clearly have enough protection against serious illness, hospitalizations, and death,” he said. “So, it’s a bit disingenuous for people to say we have all the science based on the submission of the vaccines for approval. There’s much, much more that’s come out.”

Ongoing scientific trials could even show that waiting a few more weeks might allow your immune system to respond better, which is the case with certain other vaccines, Osterholm said. “These studies were never set up to measure, ultimately, your immune response or dosing. They were set up so that you could get a product approved quickly with authorization.”

But even before new research was made public, Osterholm decided to delay his own second shot. “You have to walk the talk and talk the walk. I would be a hypocrite if I didn’t believe that vaccine wouldn’t provide me adequate protection through this surge,” he said. He believes what he says about being protected from severe illness or death by a single dose.

“I just know that there are thousands of grandpas and grandmas, moms and dads, brothers and sisters that could be protected with a single dose,” he said. “If we keep up doing what we’re doing, they’re not going to have that chance before this surge comes.”

And that surge is a major factor in why he advocates for this plan. When he first began talking about delaying doses at the beginning of the year, he said, “a lot of people just missed the surge piece completely. ‘There he goes again,’ you know. People will say I scare people, but whatever. It’s never to scare people out of their wits, it’s to scare them into their wits.”

He likens his prediction about another surge to meteorologists watching a hurricane swirl across the Doppler. If it looks like a category-five storm is headed toward the coast, they need to warn people of the potential danger—even if it downgrades or takes a turn back out to the ocean. “You had a responsibility to let the public know,” he said. “I’d much rather be sorry for something I did than something I didn’t do.”

In emergency situations, he said, you can’t wait until you have complete information, or it will be too late.

“I’m sitting here saying this surge is coming,” he said. “Do I know how big it’s going to be? I don’t. But I can tell you, in Europe, they’ve all been in lockdown since Christmas in many countries, and they still have a problem.”

Recently, on his podcast, Osterholm spoke about the professional risks of vocally backing a plan like this. “This could be the end of my career. But I could not sleep with myself at night if I didn’t do this,” he said.

In our interview, he took a lighter approach. “I mean, some people thought I ended my career 40 years ago,” he said, laughing, before sobering again. “I’ve been doing this since the beginning of time. I never for a moment forget the responsibility I have to the public, to tell the truth, no matter how hard it is, no matter who else doesn’t agree with you, and to always say what I know and don’t know.”

“I’ve tried to wrap my arms around what it means to have 500,000 people die from Covid,” Osterholm said. In their work, epidemiologists deal with numbers—with population-wide statistics and calculations. “But I know some of these numbers,” he said, his voice quiet. “They were people loved by people.”

He believes warning about a coming surge—and rallying to protect more people quickly—could be his greatest contribution to combating the pandemic. “To me, that is what’s very personal,” he said. “My job right now is just to save as many lives as possible in the next six to 12 weeks. Whatever it takes.”

Even so, decisions like these never get easier. “You always ask yourself, is this the right thing to do?” he said. “I’m not afraid of being wrong. I own it, if I am. I’m more afraid of knowing what I know and not speaking out. Because that could make the difference between whether somebody’s grandma and grandpa are going to be there to give one of their grandkids a hug and a kiss goodnight,” he said. “That’s what I worry about. I’m dispensable. Grandpa and grandma are not.”

“I want to be so wrong on this one,” he said. “I will publicly celebrate me being wrong if this [surge] doesn’t happen, because I just wish we didn’t have to go through this.”