For the first time on record, a majority of U.S. adults do not belong to a church, synagogue, or mosque.

Since 1939, Gallup has been surveying Americans on their religious affiliations. From that year until the turn of the millennium, church membership in the U.S. never dipped below 68 percent. But over the past two decades, that figure has steadily declined — and now, the emerging churchless majority has arrived.

This is not a story about the rise of “remote worship.” Declining church membership has been driven primarily by rising godlessness. On the eve of the 21st century, 8 percent of Americans identified with no religion in Gallup’s polling. Today, that figure is 21 percent.

Pew Research believes the ranks of the “nones” are even larger. In its polling, 26 percent of the U.S. public prostrates itself before no deity.

In assigning culpability for this trend, one could assemble a long list of plausible co-conspirators. The ascendance of the Evangelical right likely damaged Christianity’s brand with social liberals by associating the faith with theocratic politics, while pedophilic priests and their enablers surely drove no small number of American Catholics from the pews. In Gallup’s polling, the decline in church membership has been especially steep among self-identified Catholics, falling 18 points since 2000, compared to 9 points among Protestants.

But in all likelihood, these contingent developments only expedited America’s atheistic drift. Secularization is a secular trend. In both Gallup and Pew’s data, the main engine of ascendant faithlessness is generational churn. Two-thirds of Americans born before 1946 belong to a religious institution, according to Gallup. That drops to 58 percent among baby boomers, 50 percent among Generation X, and 36 percent among millennials (the pollster’s limited data from zoomers indicates that they are roughly as irreligious as their cooler, wiser immediate predecessors).

Pew shows a similar pattern on the question of religious identification: Each new generation is less religious than the last, while the drop-off between Gen X and millennials is especially sharp:

To be sure, one might attribute American millennials’ disaffection with religion to the fact that the Christian right (and/or Catholic church sex abuse scandal) loomed especially large during their formative years. But declining religiosity is not limited to the United States. Rates of religious-service attendance are falling in nearly every Western country. And the United Kingdom — whose Conservative Party endorsed same-sex marriage before Barack Obama did — has witnessed a remarkably similar trend to the U.S. in religious identification, with the percentage of Britons who subscribe to no religion rising 12 points since 2000.

Given that religious identification has been declining continuously with each new generation, across a diverse array of national contexts, the fundamental cause of the phenomenon is likely structural (as opposed to contingent). I can’t tell you with much authority what this macrohistorical cause is. But I’m inclined to think that industrial development inherently undermines tradition and cultivates individualism, qualities that render it an adversary of faith-based, communitarian institutions. It also seems to me that late capitalism has robbed the church of its monopoly on a wide range of social functions: The welfare state provides social insurance; the universities, metaphysics; Marvel movies, community-binding myths (what are MCU Reddit forums but Bible studies persevering?).

Regardless, my point in emphasizing the deep-seated, structural nature of declining religiosity is simple: It suggests that this trend will not be drastically reversed, absent some kind of social cataclysm.

And that poses a major challenge to the Republican Party.

America’s loss of faith may have won Biden the presidency.

Everyone knows that religion is a major fault line in American politics. But its exceptional salience has been occluded a bit in recent years, as divisions rooted in race and educational attainment have attracted heightened attention. Much digital ink has spilled on the growing split between white voters with college degrees and those without them. And rightly so. Yet it remains the case that whether a white American identifies as an Evangelical Christian is a much more reliable predictor of her partisan preference than whether she went to college.

This reality helps explain some curious aspects of contemporary politics. For example, many pundits have puzzled over the divergent political trajectories of Wisconsin and Ohio. Although both states have shifted right since the Obama era, the former has remained competitive while the latter has gone solid red. If one focuses on race and education, this split is hard to explain. Both states are heavily working-class, with nearly identical percentages of Ohioans and Wisconsinites holding college degrees, while African Americans comprise roughly twice as large a share of Ohio’s population as they do of Wisconsin’s. Thus, if you only looked at these two variables, you’d assume that the Buckeye State was the bluer battleground. But religiosity presents a countervailing distinction. In Pew’s polling, 58 percent of Ohioans say they are “highly religious,” which makes their state the 17th-most religious in the country. By contrast, only 45 percent of Wisconsinites identify as highly religious; only five states demonstrate lower levels of religiosity, and all of them are blue.

As the GOP’s electoral fortunes in Ohio (and beyond) indicate, there are worse fates than being the party of white Christians in a time of deepening education polarization. The “moral majority” may in fact be an ever-shrinking minority. But it is also disproportionately concentrated in rural areas that are overrepresented at every level of government. This reality, combined with the GOP’s Trump-era gains among secular noncollege whites — who are also overrepresented in both rural America and the Midwest’s Electoral College battlegrounds — has enabled Republicans to assemble an extraordinarily efficient coalition. While Democrats waste votes by running up the score in urban House districts and a handful of coastal states, Republicans are spread comparatively evenly across the geography of most regions, and are superabundant in the wildly overrepresented Great Plains states.

Nevertheless, geographic efficiency isn’t worth much without numerical sufficiency. In 2020, the Electoral College’s tipping-point state was nearly 4 points more Republican than the nation as whole. But the nation as a whole gave Donald Trump the lowest share of the popular vote that any incumbent president had received since Herbert Hoover. So Trump lost.

The emerging churchless majority may well have been integral to Trump’s plight. In 2016, the mogul was all things to all white cultural conservatives: His reputation as an infamous philanderer reassured a critical mass of a secular, working-class Obama voters in the Midwest that his Bible-thumping was insincere, while his avid support from megachurch pastors (and Mike Pence) kept the Evangelical right in his corner. After four years in power, however, the voting public came to regard Trump as more of a conventional conservative. And his support among the religiously unaffiliated appeared to decline: In Pew’s data, Clinton won the godless by 41 points, while Biden won them by 49.

If those figures are broadly accurate, then the shift they reflect surely helped Biden secure his narrow margins in key Midwestern states. The pious aren’t as overrepresented in the Rust Belt battlegrounds as the non-college-educated are: On Pew’s list of America’s most religious states, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and Wisconsin are all in the bottom half.

The GOP is caught between the median voter and the moral minority.

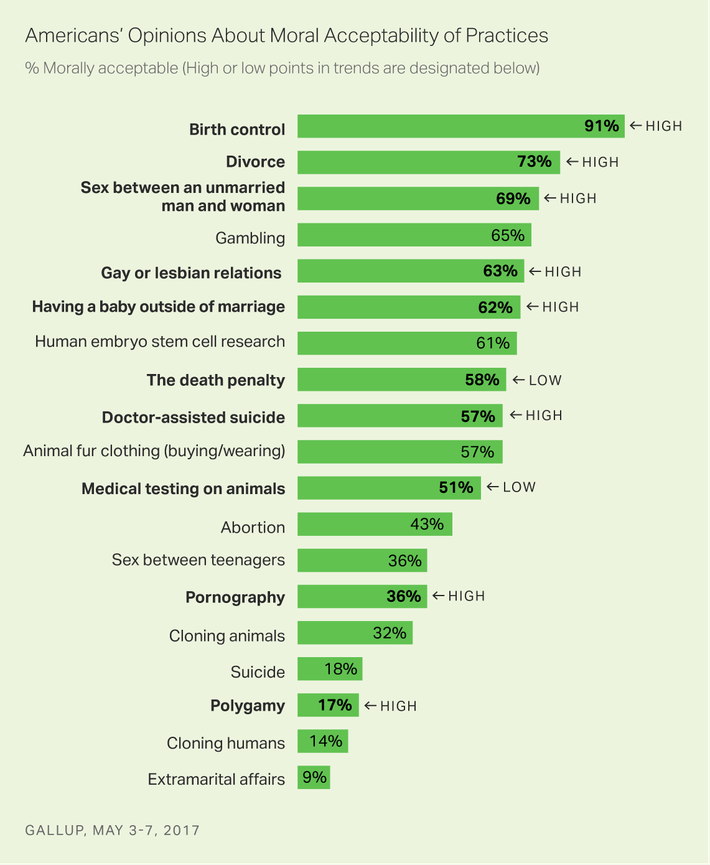

Of course, the difficulty for Republicans is less that their coalition is more religious than America writ large than that it is wildly more theocratic and reactionary. For decades, Gallup has taken the public’s temperature on the moral acceptability of various social practices. In 2017, it found that on 10 of its 19 “moral” issues, American opinion had become historically left-wing, while the electorate’s views had grown significantly more conservative on exactly zero.

This trend is all but certain to continue apace over the coming decade, since it’s driven by the same generational churn that’s emptying America’s pews. As millennials and zoomers replace silents and boomers, it will be increasingly difficult for the GOP to win national elections without distancing itself from moral traditionalism. Marijuana legalization, LGBT rights, and Roe v. Wade are all popular and becoming more so.

The challenge that declining religiosity poses to the Republican Party is therefore twofold. First, the trend directly shrinks the party’s core constituency of white Evangelicals, while expanding the core Democratic constituency of the irreligious. Until recently, the GOP may have actually benefited from the decline of Protestantism in the U.S., as erosion in church membership was concentrated in mainline congregations that were disproportionately affiliated with the Democrats. But over the past decade, the ascent of the millennials and sunset of the boomers have reduced the weight of conservative Christians in the electorate. Between 2009 and 2019, the share of the U.S. population that identified as white Evangelical (or born-again) Protestants dropped from 19 to 16 percent in Pew’s polling. At the same time, the growth in the unchurched population has directly increased the Democrats’ vote share: Since 2004, the Democratic nominee has never won less than 67 percent of the religiously unaffiliated.

The second problem is that the GOP’s most loyal and best-organized mass constituency — the Evangelical right — is increasingly out of touch with mainstream opinion. This tension has been further heightened by the exodus of college-educated professionals from the GOP coalition, which has allowed the “moral minority” to retain (if not increase) its clout within the party, even as its influence over the broader culture has steadily eroded.

Republicans have responded to this challenge in part by strategically retreating on some culture-war issues and escalating hostilities on more ecumenical ones. In 2015, the Supreme Court neutralized the wedge issue of same-sex marriage, and the GOP proceeded to drop the subject from its national messaging. Republican presidential hopefuls still cling to radical positions on reproductive rights, with Marco Rubio supporting the prohibition of abortion even in cases of rape and incest. But most have followed Trump’s lead in centering issues that unite religious and secular reactionaries, from immigration to “cancel culture” to belligerent anti-China policy.

Given the GOP’s large structural advantage in the Electoral College, it could conceivably build a winning coalition atop terror of migrants and reverence for racist Dr. Seuss books. After all, not all of our polity’s long-term trends cut against Republicans. The assimilation of Hispanic Americans into white identity is one tailwind for the party. And even the decline of religion isn’t without its upside for the right. Although the development hurts Republicans with white voters, the decline of the Black church appears to be helping them with African Americans — both because such institutions are critical for promoting Black turnout, and because unchurched Black voters are a bit less likely to adhere to their community’s traditional partisan preference.

Nevertheless, the Republicans’ dependence on an increasingly minor religious movement will be a major liability in 2024. The days of Anthony Kennedy nullifying debates that divide the Christian right from the broader populace are over. Today’s conservative Supreme Court is far more likely to increase the salience of such wedge issues than it is to sideline them. And neither Marco Rubio nor Josh Hawley nor Tom Cotton boasts Donald Trump’s innate connection with those who disdain both political correctness and piety.

The Christian right’s answer to declining religiosity is the suspension of democracy.

Whatever its impact on the GOP, the implications of creeping secularism are more dire for social conservatives. The Republican Party can ultimately retain political power by bringing its policy commitments into slightly closer alignment with public opinion. That is not an option for the Christian right’s true believers. As a result, the movement is becoming forthrightly anti-democratic. On the one hand, the moral minority hopes to impose its will on the nation by judicial fiat. On the other, it aims to disenfranchise the heathen majority.

Liberal analyses of the GOP’s war on voting rights tend to characterize it as a reaction against the nation’s burgeoning racial diversity. And this is surely one driver of the phenomenon. But it’s worth noting that the eclipse of conservative Christian America is real, while that of majority-white America is a paranoid delusion. According to Census Bureau projections, white Americans will still comprise over 68 percent of the U.S. population in 2060, so long as one includes Hispanic Americans who identify as white in that category. The complexion of America’s white majority may shift, as it has many times before. But it’s not actually disappearing. White conservative Christians, by contrast, are already a minority of the U.S. electorate.

It’s not surprising then that many of the right’s most unabashed advocates for authoritarianism hail from its religious wing. And while no respectable conservatives will publicly argue that nonwhite Americans are unfit for self-government, many are quite comfortable saying as much about the nation’s socially liberal majority. Glenn Elmers, a senior fellow at the Claremont Institute and research scholar at Hillsdale College, made the case vividly this week:

[M]ost people living in the United States today — certainly more than half — are not Americans in any meaningful sense of the term … They do not believe in, live by, or even like the principles, traditions, and ideals that until recently defined America as a nation and as a people. It is not obvious what we should call these citizen-aliens, these non-American Americans; but they are something else …

Authentic Americans still want to have decent lives. They want to work, worship, raise a family, and participate in public affairs without being treated as insolent upstarts in their own country. Therefore, we need a conception of a stable political regime that allows for the good life. The U.S. Constitution no longer works.

The Republican Party can still compete for political supremacy within America’s existing institutions. But its moral traditionalists cannot regain cultural hegemony absent some kind of a counterrevolution. If such a project is practically implausible, it is increasingly ideologically permissible on the right side of the aisle. Thus, the coming decade of U.S. politics may be defined, in part, by the struggle to prevent conservative Christianity from taking democracy down with it.