From the outside, Governor Gavin Newsom looked at least somewhat vulnerable for a lot longer than you might expect of a Democrat in California. His state was hit especially hard by the pandemic, and many residents soured on his immediate lockdown order, which was later followed by two more. His approval numbers continued to dip as local restrictions were (inconsistently) put in place and the southern part of the state was hammered by soaring infections and deaths. Then there was his impossibly dim unforced error: Last November, Newsom decided to dine with political allies at the notoriously fancy and expensive French Laundry restaurant in Napa just as the state was tightening its COVID rules, a display that was especially grating on voters. The state’s vaccine program was, for a while, slow and confusing. A petition to recall Newsom collected 1.5 million signatures last month, and the governor now faces a fall vote that will determine his political future. It’s the kind of unpredictable contest that put Arnold Schwarzenegger in the governor’s mansion 18 years ago. And, at least in theory, Newsom could get a real scare.

Yet at each turn in this young race, the Republicans trying to unseat Newsom — or, more realistically, trying to make a point against him — have made a hash of what ought to have been a political opportunity, almost always because they’ve misread the moment, and misgauged their exhausted voters’ appetite for spectacle and celebrity.

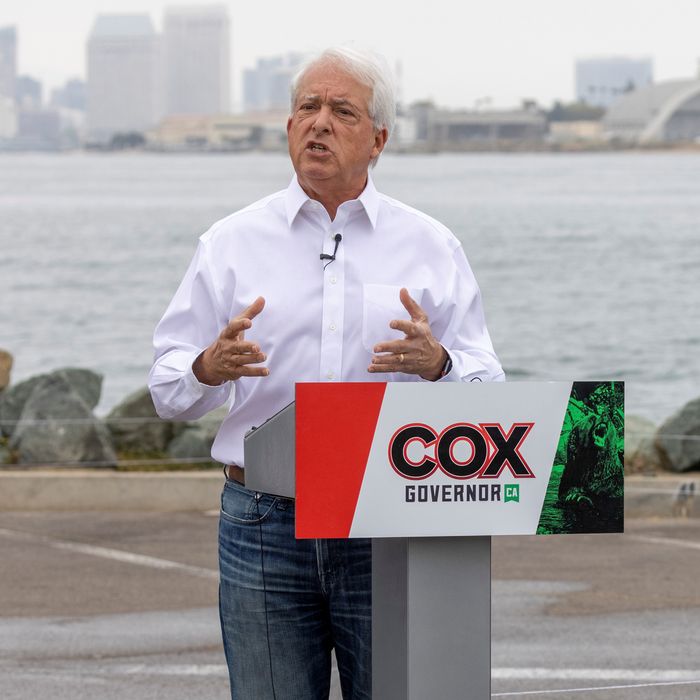

Maybe it was obvious after perennial candidate John Cox launched his latest gubernatorial bid in Sacramento next to a rented Kodiak bear named Tag, only to complain that all anyone cared about was his 1,000-pound guest. Cox, who lost his last statewide campaign to Newsom by 24 points, then held an event without Tag. No one showed except for one photographer.

Or maybe it became clear the next day, when Caitlyn Jenner debuted as a candidate on Sean Hannity’s show inside her private Malibu airplane hangar by explaining that the owner of a neighboring hangar left California because he didn’t care for its homeless population. In the first polls after she announced her campaign, which is led by former senior Donald Trump staffers, she drew just 6 percent support.

At some point last week, California Republicans engineering the recall and some incorrigible swaths of the political media-industrial complex faced an inescapable truth: They can’t expect anything more than hollow attention and anemic support if they’re just going to rely on reflexive provocations, spectacle, and a splash of celebrity to beat Newsom. They have mislearned some fundamental lessons if they think that’s how Trump won — and these performative antics had little to do with Schwarzenegger’s 2003 success, either.

The effort started to show teeth when a judge extended the usual deadline for gathering signatures to recall Newsom in early November, thanks to the pandemic. That gave the organizers — an amateur conservative activist who was soon joined by professional Republicans and then the national party — 120 extra days to find potential allies on the ground just as Trump was revving up the GOP money and outrage machines to try and overturn the election. Newsom helped their cause with the French Laundry debacle that month. “They got lucky,” said longtime California Republican strategist Mike Madrid, who has turned into a critic of his party in the Trump era. “These things happen all the time — there are always angry cranks on the right who are pissed about something. There’s always a petition on the recall circulating, always.” Still, he said, “You could make a very good case that this one caught fire because of the pandemic, because they had the extension.”

Newsom’s missteps set off a wave of frustration that had been building for months. By January, a Berkeley/IGS poll revealed that less than a third of the state said Newsom was doing an excellent or good job on handling the pandemic, and just over one in five approved of his work on vaccine distribution. Yet as health and economic conditions improved this year, proponents of the recall failed to coherently dig in on the pandemic that Newsom was catching grief over. Instead, they leaned even harder on conservative grievances: The official petition’s language complains about undocumented immigrants and tax rates — it doesn’t mention the virus.

Meanwhile, Newsom’s lot brightened. By mid-May, California was averaging around 1,700 new COVID cases per day, down from a peak of nearly 45,000 in December. An early May survey by the same pollster revealed that now nearly half the state thought Newsom had done an excellent or good job overall, and more than half approved of his vaccine work. About half now oppose the recall altogether, versus just over a third who back it. “Assuming things continue improving, memories are so damn short that eight months from now people are not going to still be feeling the effects of the pandemic and voting on it,” said Madrid.

Where their political fortunes darkened, Newsom’s opponents figured they were at least attracting a promising set of candidates who could presumably draw headlines. Jenner, a bona fide famous person with some Trumpworld backing, was one, and Cox, who was decently well known as a result of his last statewide run, was another. There is also former Sacramento area congressman Doug Ose and former San Diego mayor Kevin Faulconer. The ex-mayor has been preparing to run statewide as a (relative) moderate for years and entered the race with straightforward fanfare, but he, like the ex-congressman Ose, has been overshadowed by splashier candidates and has veered hard to the right to gain traction. Still, Faulconer was attacked in March when Donald Trump Jr. sniped at him for not supporting his father clearly enough.

Yet the parade of contenders may be marching nowhere fast, despite the flood of attention on Jenner in particular, who launched her campaign far more as a culture warrior than a wannabe technocrat aiming to fix the state’s crisis response. On CNN, she said of immigrants that “the bad ones have to leave” and refused to name the “budget people” she said she’d been meeting with. “It’s a pretty weak field, but there’s an extraordinarily weak bench in California after years of decimation,” said Madrid. “At this moment in time it’s going to be a 60-40 race, which is the standard baseline for Republican level of support.”

The recall has two components: First, voters will render a verdict on Newsom. Then — and only if Newsom is voted out — the other candidates will be considered. As such, they’re not directly running against him, and he’s free to ignore them or cherry-pick their outrages as he wishes, a relatively risk-free proposition given his 52 percent overall approval rating in the latest polling.

And then there was the vague hope that, well, it worked for Arnold — if nothing else, the vague memory of 2003’s famously zoolike recall of then Governor Gray Davis would likely draw national media attention. (The former porn actress Mary Carey, who famously ran that time, is back in the race this time, but two other celebrities who threw their hats in the last ring, Larry Flynt and Gary Coleman, have since died.) Even more elementally, though, Newsom is now far more popular than Davis, a Democrat who was bedeviled by an energy crisis. That popularity is especially important on the left, since it is helping Newsom avoid one of the central dynamics to Davis’s downfall: His lieutenant governor Cruz Bustamante entered the 2003 recall race, essentially splitting Democrats when it came time to vote. No other Democrat is running to replace Newsom; his party is unified behind him as California’s condition brightens.

But as Newsom’s political standing rebounded this spring, the fundamental differences between that landscape and today’s only grew more stark. For one, Schwarzenegger — like Trump — had for years built a universally recognizable and (to many) aspirational reputation. That isn’t true for Jenner, today’s top celebrity candidate who first made news as a candidate by relying on exiled Trump campaign manager Brad Parscale and then by telling TMZ that she, a transgender former Olympian, opposes transgender athletes participating in girls’ sports. This was soon after she appeared to reveal not knowing that district attorneys are elected, not appointed. She has tried weaving her way past the Trump questions, too: After saying she was in favor of Trump’s wall to be built on the California-Mexico border, she went on CNN to insist she didn’t vote in 2020 and shied away from calling herself a Republican. (The next day Politico revealed that, well, actually, she actually did vote.)

Still, the Berkeley poll in May showed Republicans are far more engaged with the effort than Democrats and independents so far, so national Democrats are not leaving anything to chance. Biden endorsed Newsom as soon as White House press secretary Jen Psaki was asked about the race, and Biden’s political shop, which is full of California politics veterans, has been keeping tabs on the race and coordinating with the Democratic Governors Association. (Newsom has long shared parts of his inner circle with Kamala Harris, and he has been close to Nancy Pelosi for years, too.) That’s it so far, though, since it’s too early for Biden to actually do anything substantive for Newsom (like cut an ad), and, as president, he has shown little interest in wading into messy political fights with no obvious upside.

In public, Newsom has been primarily focused on showcasing his pandemic response. He recently announced that the state is working with an unexpectedly massive $75.7 billion surplus, and he has begun showing off his new plans: On Monday, he talked about new $600 stimulus checks, tax rebates, and rent relief; on Tuesday, in San Diego County, a new $12 billion plan to fight homelessness; on Wednesday, an effort to expand kindergarten access while promising a huge spike in school funding.

“I think the governor has to have an austerity summer for himself — just show us he’s 100 percent focused on the job, which will be a stark contrast with one celebrity candidate saying she wants to fly away from homeless people and somebody else posing with a bear and somebody else who was unable to fix the divides within his own city,” said longtime state party operative Christine Pelosi, the Speaker’s daughter. “If those are our options, we’re not going to get to the second question” on the recall ballot of who should replace Newsom.

Newsom, meanwhile, launched his counter-campaign to the recall a month before the signature deadline and called the effort a “partisan political power grab” in his March “State of the State” address. His campaign committee is officially called “Stop the Republican Recall of Governor Newsom,” and his allies have seized every opportunity to point out that anti-vaxxers, Proud Boys, and QAnon supporters have all been present at recall rallies and in online discussions of the push. “Why is the Republican National Committee behind this?” Newsom asked rhetorically in a press conference last week, making a point his campaign has been hammering in its text outreach program and which it plans to include in an ad campaign. (The RNC in February put a quarter-million dollars into the signature-gathering effort.) “Why has an entire network dedicated so much time and energy and attention to this?”

The individual Republican candidates may not need to answer that question, but each is already finding that they need to at least articulate a much clearer rationale for their own campaigns beyond the spectacle. The Berkeley poll found Cox and Faulconer leading the field at 22 percent support, with Ose at 14 and Jenner at 6.

And then there’s the more obvious political reality that each of the Republicans has refused to acknowledge. The state has changed dramatically since 2003, the Republican Party’s reputation having been brutally trashed in California over the past two decades. It may only be 2 percent more Democratic in terms of party registration, but it’s 11 percent less Republican. And though California has grown no less celebrity-friendly since Schwarzenegger won, when he replaced Davis, Al Gore had recently beaten George W. Bush by 11 points there; last year, Joe Biden beat Trump by 29. The state hasn’t elected a Republican to a statewide office since Schwarzenegger was reelected. While Faulconer, Cox, and Ose may have found some reason to cheer in the poll showing them with double-digit support, more than two times as many Californians say they’re not inclined to support each of them than back any of them. As for Jenner, who came in at 6 percent just after launching her campaign? Over three-quarters of voters said thanks, but no thanks.