This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

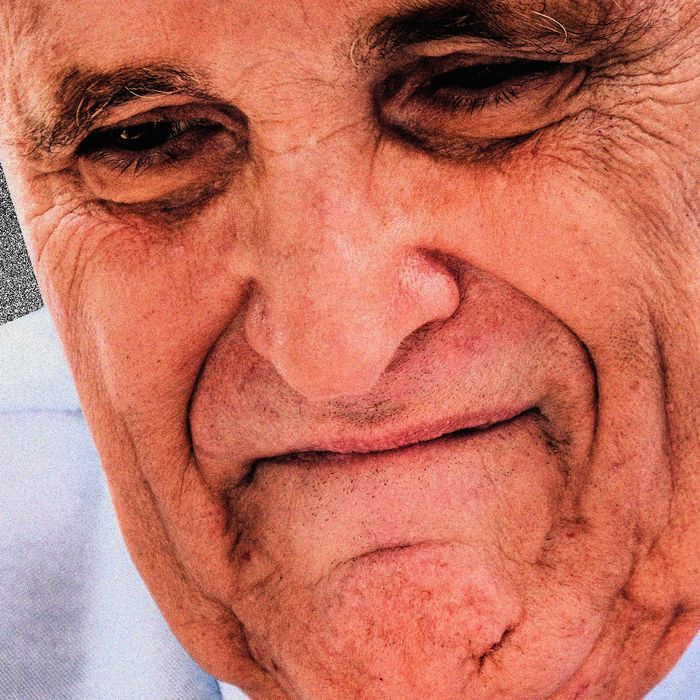

Has any political figure in recent years fallen farther and harder than Rudy Giuliani? On the eve of September 11 — the 20th anniversary of the day that catapulted him into national renown — Fox News told him that he had been banned from appearing on the network, likely because Giuliani had helped land Fox in hot water for claiming that two election-technology companies had helped rig the election in favor of Joe Biden. Dominion Voting Systems and Smartmatic have since filed separate billion-dollar defamation lawsuits against both Fox and Giuliani, who is embroiled in so many costly legal shenanigans these days that he has apparently resorted to selling personalized video greetings over the service Cameo for a few hundred dollars a pop.

On top of that, his law license was suspended in New York and Washington, D.C., after he repeatedly lied to courts and in public statements to help Donald Trump overturn the 2020 election results with baseless charges of widespread fraud. He is reportedly “aghast” that Trump has declined to help him out financially, despite the fact that Giuliani, as Trump’s onetime personal lawyer, had been his fiercest henchman. Giuliani has gotten so desperate that his allies launched a Rudy Giuliani Freedom Fund, replete with an endorsement from tarnished lawyer Alan Dershowitz, that blasts “deep state” forces for Giuliani’s legal morass.

Giuliani is being treated, by all appearances, as a dead man walking. America’s Mayor, as he was once known, has been abandoned by his most powerful friend. He has lost his megaphone at Fox News and is now going around with a begging bowl for money. And at the center of Giuliani’s legal troubles is a web of overlapping federal investigations, including a criminal probe focusing on him personally, which some experts say could force him to yield to prosecutors in a case that may implicate the former president.

“Giuliani is facing a set of challenges unlike anything he’s dealt with before,” Michael Bromwich, a former inspector general at the Justice Department, told me. “The extremely serious criminal investigation that could send him to jail, the civil suits that could bankrupt him, the disbarment proceedings that may well end any opportunity to practice law ever again — it’s a tidal wave of problems with potentially devastating personal and professional consequences.”

Bromwich added, “It’s hard to think of any analogous case where a person who once rode so high — as a prosecutor, a New York mayor, a serious presidential candidate, and an international figure — has been brought so low in so many ways and where the damage has been entirely self-inflicted.”

If Trump’s conspiratorial crusade against the phantom of election fraud ensnared Giuliani in potentially ruinous civil lawsuits, it was Trump’s unscrupulous campaign against Joe Biden and his son Hunter that goaded Giuliani into consorting with the shady operators who are now in the crosshairs of American criminal prosecutors. One of those men, Ukrainian-born Lev Parnas, is due to be tried on October 12 on charges of making illegal campaign donations from a foreign source. Another Soviet-born operator, Igor Fruman, pleaded guilty in September to the same offense. Parnas and Fruman, who have lived in Florida for some time, were key allies in helping Giuiani dig up dirt on the Bidens in Ukraine in the run-up to the 2020 election.

Giuliani has not yet been charged with any crimes. Nor has he been implicated in the illegal-donation schemes that led authorities to nab Parnas and Fruman. Rather, the criminal inquiry into Giulani is focused on whether Trump’s former lawyer, during his sprawling fishing expedition with Parnas, Fruman, and others in Ukraine, violated the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), a decades-old law that requires people who lobby the U.S. government on behalf of foreign officials or entities to disclose their activities to the Justice Department. Giuliani may also have legal headaches stemming from separate federal fraud charges against Parnas and a federal investigation into a Ukrainian politician suspected of meddling in the 2020 election.

“As Giuliani looks over the landscape he faces, it appears there are legal storm clouds in three separate matters, all of which could have potentially serious consequences for him,” said Michael Zeldin, a former federal prosecutor.

While we have grown accustomed to members of Trumpworld being mired in lawsuits, it is worth underscoring that Giuliani is confronting extreme levels of legal and financial risk — and he has few, if any, good options. “The emotional and financial pressure of a single long-term federal white-collar investigation can take a crippling toll on any target of such an investigation,” said Paul Pelletier, a former acting chief of the Justice Department’s fraud section. “Enduring multiple investigations, in addition to bar disciplinary actions and financial pressures, creates an enormous incentive to alleviate that pressure in some way. The only logical ways I know of are to plead guilty, cooperate, or both.”

The budding criminal case against Giuliani seems to have been jump-started by his extensive dealings with Parnas and Fruman, who were arrested at Dulles airport in October 2019 before they could hop on a flight to Vienna. Giuliani had tapped the two men to arrange contacts in Ukraine, including current and former prosecutors, who could help him develop and push conspiracy theories about Hunter Biden, who sat on the board of a Ukraine gas company. Trumpworld’s attempt to use a foreign power to damage the former president’s political opponent, as you may remember, was the basis for his first impeachment, in December 2019.

It was also, apparently, a major catalyst behind FBI agents’ raid of Giuliani’s New York office and apartment in April of this year, in which they seized 18 cell phones and computers. The raid signaled that Giuliani could face charges of illegal foreign lobbying — and perhaps more — from the same Manhattan U.S. Attorney’s office he once led.

“The fact that a judge issued the warrant, despite the high bar for obtaining one, would seem to indicate that Giuliani is at least a subject of what appears to include violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act,” Zeldin said, noting that “the warrant lists a who’s who of Ukrainian officials with whom Giuliani is believed to have been working in 2019–20.”

“If past is prologue, the search warrants conducted on the phones and electronic devices of Giuliani and his associates should soon begin bearing a cornucopia of fruit,” Pelletier told me. “That type of electronic evidence typically reveals compelling evidence of the criminal scheme outlined in the search-warrant affidavit. If and when that happens, the walls should close in pretty quickly on Mr. Giuliani and any identified criminal cohorts.”

The FBI also seized other electronic devices from the Washington, D.C., residence of conservative lawyer Victoria Toensing. A Giuliani ally, Toensing had a $1 million contract in tandem with her lawyer husband, Joe diGenova, to represent a billionaire Ukrainian oligarch, Dmytro Firtash, who had aided Giuliani’s Ukraine gambit, according to news reports. (Firtash denies having any communications with Giuliani or any involvement in efforts to dirty up the Bidens.) After the raid, Toensing said she was told she herself was not a target in the federal inquiry.

Giuliani and his attorney Robert Costello have vociferously denounced the FBI’s raid. Giuliani issued a statement boasting that his “conduct as a lawyer and a citizen was absolutely legal and ethical” and told Fox News, back when he was still in the network’s good graces, that prosecutors were “trying to frame him.” Giuliani has repeatedly denied lobbying for any foreign officials or entities.

Costello blasted the raids as “legal thuggery.” A former federal prosecutor in Manhattan, Costello stressed that his client agreed twice to answer prosecutors’ questions — with the exception of ones touching on privileged talks with Trump — and was turned down. Costello has said that Giuliani’s defense will rest in part on attorney-client privilege. (Costello did not return requests for comment.)

After the raid, a special master was appointed by a New York court to review whether the material seized by the FBI was protected from government scrutiny by attorney-client privilege. In September, a federal judge in New York nixed Giuliani’s request to have some of that material returned to him or destroyed, but a subsequent ruling limited what prosecutors could use to those materials dating from 2018 onward. Justice Department officials had likely anticipated such challenges. Mary McCord, a former prosecutor who used to lead the the department’s national security division, told me that approval for the raid “would not have been given absent very solid grounds.”

Judging from Parnas’s past public statements, too, the probe of Giuliani is serious. During Trump’s impeachment, Parnas made no secret in interviews that he took his cues from Giuliani and Trump as they tried zealously to find current and former officials in Ukraine to blemish Biden, linking his actions as vice-president under Barack Obama to Hunter’s Ukraine gig.

Parnas told Rachel Maddow in early 2020, “I wouldn’t do anything without the consent of Rudy Giuliani or the president.” Parnas stressed that high-level officials in Ukraine would have ignored him unless it was clear that he was their emissary. “That’s the secret” Trump administration officials were “trying to keep,” he said. “I was on the ground doing their work.”

During Trump’s impeachment, Parnas and his lawyer gave House investigators a trove of potentially incriminating materials, including a video of Parnas and Fruman dining with Trump at a Mar-a-Lago fundraiser in April 2018 and a photo of the two Giuliani pals dining with Donald Trump Jr. and a top Republican National Committee official at a swanky Beverly Hills hotel in 2019. Parnas has suggested the photos and other documents support his claim that Trump “knew exactly what was going on.” In response, Trump has said that he barely knew him.

Parnas and Fruman have been accused by the feds of making several illegal donations, including a $325,000 check to a pro-Trump Super PAC that was written not long after the two men attended a small dinner at Trump’s Washington, D.C., hotel on April 30, 2018, for PAC donors. There, they chatted with Trump, an encounter that Fruman recorded. Parnas raised dark concerns about the loyalty of the U.S. ambassador in Kiev, Marie Yovanovitch, that quickly prompted Trump to ask a nearby White House aide to “take her out” — which Trump did about a year later when he yanked her from the Kiev post. Her ouster was a key focus of Trump’s first impeachment and has reportedly figured in the Giuliani probe. Giuliani told The New Yorker in 2019, “I believed that I needed Yovanovitch out of the way. She was going to make the investigations difficult for everybody” by frustrating his attempts to get help from Ukrainian sources.

Former Justice Department officials see more trouble ahead. Gerry Hebert, who spent more than two decades as a senior lawyer in the voting-rights section at the department, said, “Parnas’s likely conviction may lead to his cooperation before he’s sentenced to prison … With his personal freedom at stake, the walls are closing in on more than just Giuliani’s legal career.”

There’s much, much more, though no other ongoing case appears to threaten Giuliani, criminally speaking, quite as directly as his dealings with Parnas and Fruman. Here is a summary of Giuliani’s other potential legal headaches:

(1) The New York Times has reported that federal prosecutors in Brooklyn are investigating election meddling involving a Ukrainian politician, Andrii Derkach, whom U.S. officials sanctioned in September 2020 and accused of having been an “active Russian agent” for more than a decade. Giuliani met at least twice with Derkach, in Kiev and New York, and appeared with Derkach on the far-right One America News Network in 2019 and a podcast in 2020 to peddle dubious claims to damage Biden. Although Giuliani initially called Derkach’s unsubstantiated claims about the Bidens “very helpful,” he switched to damage control after the news broke that the White House had received warnings that Giuliani was being targeted by a Russian influence campaign involving Derkach.

(2) Parnas faces a second trial for allegedly defrauding investors in a scam company he helped set up that funneled Giuliani $500,000 in consulting fees for his legal and technical services in what could have been a ploy to lure investors using Giuliani’s name. The company, named Fraud Guarantee of all things, was billed as a venture to protect its investors against corporate fraud, but it bilked those same investors of some $2 million, according to the indictment. Parnas’s business partner David Correia pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit wire fraud in late 2020, but he declined to cooperate with prosecutors and was sentenced to one year in jail. Parnas has pleaded not guilty and is slated to be tried separately on fraud charges after his first trial in October.

(3) According to Bloomberg, Giuliani faces a separate foreign-lobbying inquiry by federal prosecutors in his old office, who are looking into whether he may have been lobbying for Turkey in prodding the Trump administration in 2017 to drop charges against his law client Reza Zarrab, an Iranian-born gold trader based in Turkey who was accused of plotting to illegally funnel $10 billion to Iran despite sanctions against the country. Zarrab wound up copping a guilty plea and implicating Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in the scheme. The investigation, which reportedly is a civil and not a criminal one, is also looking into whether Giuliani lobbied Trump to deport Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen, a move the Washington Post has reported was a “top priority” of Erdogan’s.

It is the federal inquiry into Derkach that touches most closely the developing FARA probe of Giuliani, though it’s not publicly known how much attention is focused on their dealings and the Times says Giuliani himself is not a subject of the investigation. Still, ex-prosecutors tell me that Giuliani must be feeling the squeeze. Giuliani last year hurriedly distanced himself from past comments praising Derkach’s help by saying that Derkach had only provided him with “secondary information.” He also told the Washington Post that he was never informed that Derkach had ties to Russian intelligence.

On top of the ongoing probes, Giuliani’s two law license suspensions could have severe repercussions, particularly as they relate to the defamation suits that have been filed against him by Dominion and Smartmatic.

In late June, a New York appeals court suspended Giuliani from practicing law in the state on account of the serial false comments he made during his obsessive campaign to get courts to block Trump’s loss in the election. In its ruling, the court said Giuliani’s “misconduct cannot be overstated. This country is being torn apart by continued attacks on the legitimacy of the 2020 election and of our current president, Joseph R. Biden.” A Washington, D.C., court followed New York’s actions with its own suspension order, and permanent disbarment in New York seems a real possibility.

“The decision by the New York court to suspend Giuliani’s law license could be a very bad omen for Giuliani in the Dominion Voting Systems and Smartmatic defamation lawsuits,” Zeldin, the former prosecutor, told me. The court found that “there is uncontroverted evidence” that Giuliani “communicated demonstrably false and misleading statements to courts, lawmakers and the public at large in his capacity as lawyer for former President Donald J. Trump and the Trump campaign in connection with Trump’s failed effort at reelection in 2020.” As Zeldin noted, “These are the issues at the heart of the defamation actions.”

In August, a federal judge ruled against Giuliani’s attempt to dismiss the Dominion lawsuit. A lawyer for Giuliani last month said that he still believes some of his claims about fraud remain “substantially true.”

As the legal screws have tightened, Giuliani has remained defiant. In an August interview with NBC, Giuliani proclaimed that he was more than “willing to go to jail if they want to put me in jail. And if they do, they’re going to suffer the consequences in heaven. I’m not. I didn’t do anything wrong.”

While some experts say Giuliani, if he faces charges, will likely fold before going to jail, others are not so sure. Bromwich, the former inspector general, cautioned, “We don’t know the strength of the case prosecutors are building against Giuliani or when they will reach a decision on whether to bring charges.” And if Giuliani is charged, Bromwich said, “even in his current, diminished state, it’s hard to imagine him crying uncle. I would expect him to fight any criminal charges to the bitter end.”

One problem for Giuliani is that prosecutors have extra motivation in pursuing him, given the zealous lengths he has gone to undermine the democratic system that the Justice Department is supposed to protect. “Giuliani has made himself a very attractive target for prosecutors, because of who he is and what he’s done,” said Stephen Gillers, a New York University law professor. “Prosecutors may view taking down Giuliani as a significant career achievement.”

Gillers added, “Giuliani has more than embarrassed the department. He’s betrayed what they hold dear, and that’s a motivating factor for going after him, if the proof is there.”

But there is no one that Giuliani has embarrassed more than himself. “It appears that Rudy Giuliani’s world is collapsing around him,” veteran GOP operative Charlie Black told me. “That is really sad. He was a national hero after his service to New York City, but getting tangled up with Donald Trump has brought a lot of trouble to Rudy.”