This is very much a back-to-the-future moment in American politics. Crime, inflation, school-curriculum wars, and even Red-baiting are in the news again and making appearances in Republican political ads. But as Perry Bacon Jr. argues in a provocative column on “white appeasement politics,” another familiar theme underlies a lot of the newly aggressive GOP messaging: white racial grievances. Bacon fears that defensive Democrats, panicked about their low and sinking electoral performances among certain categories of white voters (e.g., culturally conservative and non-college-educated ones) may be tempted to distance themselves from their expanding non-white voting bases and go back to the old southern Democratic strategy: expecting minority voters to loyally back centrist white candidates as far better than the GOP alternatives.

Fearing that candidates of color will alienate white swing voters is an ancient impulse. Two practical objections can be made to it. The first is that political parties that refuse to represent loyal constituencies on the ballot may soon find themselves losing some of their votes. This is a particularly serious threat given signs in 2020 and 2021 of softening enthusiasm for the Democratic Party among Black and especially Latino voters. The second is that appeasing white voters (as Bacon puts it) by running candidates who look and sound like them doesn’t really seem to work very well:

The Virginia race is instructive here. Democrats nominated McAuliffe over several other candidates in the Democratic primary, including two Black women. During his general election campaign, McAuliffe reversed his previous support for a key plank of police reform — getting rid of qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that limits civil suits against officers. So Virginia Democrats took steps right out of the White appeasement playbook — run a White male candidate, move right on racial issues — and lost.

Now it’s probably not fair to assume Virginia Democrats nominated McAuliffe primarily because he was white or because he was willing to hedge a bit on the commitments to racial justice that have been so central to Democratic governance in the commonwealth since the party won trifecta control in 2019. He’s a former governor with universal name ID, unparalleled fundraising prowess, and a solid history of support from and work for non-white Democrats. But the question remains in Virginia and elsewhere: If you are going to lose the votes of racially resentful white voters anyway, why not begin to build the coalition of a more demographically diverse future with candidates who finally offer non-white voters better representation? At some point, the kind of backdoor arrangement between white Democratic leaders and non-white followers stops being prudent and starts being actively offensive.

Interestingly enough, the transition to a new model for Democratic success has progressed more in parts of the South where white racial backlash is a constant reality, as I noted in 2018:

Until very recently, the Democratic constituency of the South was an uneasy coalition of disgruntled, conservative white voters perpetually on the brink of defection and loyal Black voters who felt unappreciated and underrepresented. At different paces in different states but all throughout the region, a new suburban-minority coalition is emerging. It may never achieve majority status in areas that are too white or too rural to sustain it. But it is showing great promise in enough states to make the South’s political future an open question for the first time in this millennium.

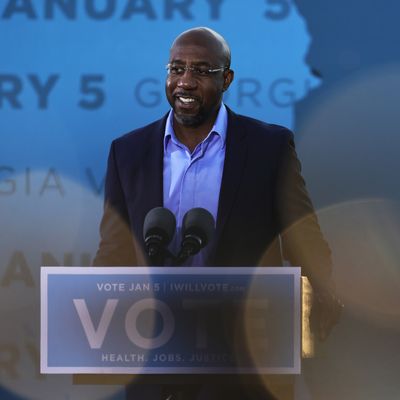

Notably, Black 2018 gubernatorial candidates Stacey Abrams of Georgia and Andrew Gillum of Florida improved on the performance of their white centrist predecessors, though both fell short by heartbreaking (and in Abrams’s case, controversial) margins. In 2020, Black Senate candidate Jaime Harrison (now the DNC chairman) threw a big scare into South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham. A couple of months later, these near victories for Black southern Democrats culminated in the election of Raphael Warnock in a Senate runoff in Georgia. This was a development that would have baffled the old (and in some quarters, still reigning) conventional wisdom about race and politics in the former Confederacy.

In 2022, we will likely see a return of the kind of savage contest between Abrams and Republican Brian Kemp in Georgia, which could pose a new test as to whether white racial resentments are truly on the rise. Warnock himself will face the particular challenge of being opposed by a Black Republican celebrity, football legend and Trump friend Herschel Walker, who will likely campaign on “election integrity” themes designed to arouse racist conspiracy theories about non-white voters.

Whatever happens in these races, it’s precisely the wrong time for Democrats to abandon their new commitment to a more reciprocal relationship with their base in pursuit of vanishingly small swing-voter categories that could be unreachable. If they don’t panic and keep making progress, Democrats still may not escape the historic pattern of midterm losses by the president’s party. But they can build a foundation for a united and growing party in the very near future.