Earlier this month, Gallup gauged American sentiment toward 11 of the nation’s most prominent public figures. Only one boasted majority support from both Democrats and Republicans, and he happens to be the most effective conservative politician of the modern era.

During his tenure on the Supreme Court, Chief Justice John Roberts has voted to gut the Voting Rights Act, ban limitations on corporate political spending, effectively legalize most forms of political bribery, rewrite the Affordable Care Act in a manner that cost millions of Americans access to Medicaid, restrict the capacity of consumers and workers to sue corporations that abuse them, nullify state-level school-desegregation efforts, sanction partisan gerrymandering, and carve gaping loopholes into Roe v. Wade.

And Roberts nevertheless retains the approval of 55 percent of Democratic voters (along with 57 percent of Republican voters) in Gallup’s new poll. No other official in the survey — not Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, either party’s congressional leadership, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, or Dr. Anthony Fauci — claimed majority support in both blue and red America.

For progressives, this is a troubling finding, if not an entirely surprising one. The disconnect between the Roberts Court’s reactionary jurisprudence and its benign public image is long-standing. Thanks in part to a pair of high-salience 5-4 rulings that delivered victories for liberals — Roberts’s decision to preserve the bulk of the Affordable Care Act in 2012 and former justice Anthony Kennedy’s to honor same-sex couples’ right to marry in 2015 — Democrats actually expressed more approval than Republicans for the majority-conservative Supreme Court for much of last decade.

Still, the Roberts Court isn’t what it used to be. Kennedy is gone, and Brett Kavanaugh, a longtime GOP apparatchik who cast himself as a victim of Clintonian persecution at his confirmation hearings, has taken the former “swing” justice’s place. Meanwhile, Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s erstwhile seat is now occupied by Amy Coney Barrett, possibly the most right-wing justice in the Court’s modern history. The conservative majority has thus grown both larger and more reactionary. And that development threatens to decide decades-long “culture war” battles in the right’s favor.

Chief among these is the fight over reproductive freedom. The Gallup survey was conducted in the immediate aftermath of oral arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. At issue in that case is whether states are constitutionally forbidden from outlawing abortion in cases where the fetus has not attained viability (which generally occurs around the 24th week of pregnancy). The Supreme Court upheld this standard in 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey. In 2021, however, the Court’s conservatives indicated at oral arguments that they were not inclined to preserve the rights established by Roe and affirmed by Casey. And Roberts was by no means an exception.

Nevertheless, despite high-profile coverage of the case and consistent majority support for Roe in opinion polls, Roberts managed to retain his status as an exceptionally non-polarizing public official.

Which is somewhat alarming. According to one recent analysis, conservatives are now likely to retain a majority on the Supreme Court into the 2050s. If the Court’s right-wing majority finds that it can continually push the boundaries of conservative judicial activism without undermining its own popular legitimacy, then the consequences for progressivism and popular democracy could be dire.

In some respects, the conservative movement’s focus on the courts has been a testament to its weakness. There is no popular majority for banning abortion, scaling back the welfare state, or eroding basic labor and consumer protections in the United States — and judging by the millennial and Zoomer generations’ political views, there never will be. Under Trump, the right responded to this reality by rapidly stocking the judiciary with as many 40-something reactionaries as it could find.

Some liberals look at this aspect of the Trump legacy and comfort themselves with the thought that the courts are a weak institution: John Roberts commands no divisions, judicial review is not in the Constitution, and, historically, the Supreme Court has adjusted its jurisprudence to match prevailing political sentiment.

But this is little consolation if the Roberts Court can abet minority rule while retaining majority approval. And to a great extent, it has already done so: The chief justice managed to gut one of the civil-rights movement’s signature legacies, the voting-rights bill — right after the Senate had unanimously reauthorized it — without forfeiting his aura of moderate statesmanship.

The big question looming over America’s judicial politics has been: What happens when the 6-3 court comes for Roe? Or the rights of blue states like New York to tightly regulate handgun ownership? Or various other pillars of the contemporary culture-war settlement?

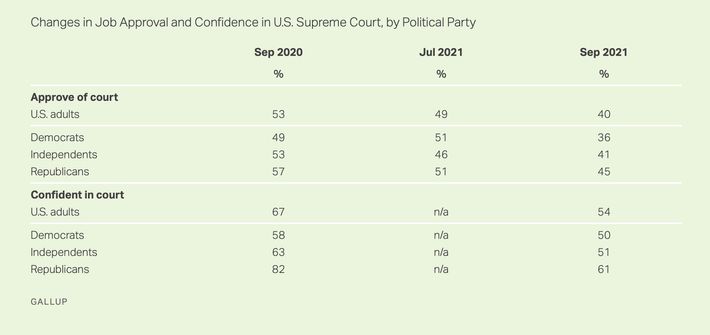

There is some basis for believing that the Roberts Court is about to discover the limit of the public’s tolerance for right-wing minority rule. In September of this year, shortly after the Supreme Court declined to preempt a Texas law that effectively banned abortion through vigilante justice, approval of the Supreme Court cratered in Gallup’s polling. As of July 2021, 49 percent of Americans approved of the Court, including 51 percent of Democrats. Two months later, those figures had fallen to 40 and 36 percent, respectively.

Gallup’s September poll may prove to be an outlier. Never in the pollster’s history had it found such low approval for America’s high court. And the fact that just three months later it found a supermajority of Americans approving of John Roberts underscores the possibility that September’s results mainly reflect a distorted sample.

On the other hand, it is possible that the September figures reflect discontent about the Court’s initial ruling on the Texas abortion law and therefore offers a preview of a broader and more intense backlash to come.

And yet even if public opinion turns against the Court, it’s not clear that progressives will be in a position to translate that backlash into meaningful reform. Overturning Roe may be unpopular. But so is expanding the Supreme Court. Amid the Amy Coney Barrett hearings in 2020, a New York Times/Siena College poll found that 58 percent of Americans opposed increasing the number of justices on the high court, while 31 percent supported it. It is difficult to see how the Court’s power could be meaningfully checked, at least in the medium term. To force Joe Manchin’s hand on Supreme Court reform, the backlash to the Roberts Court would need to extend far into red America. After the 2022 midterms, meanwhile, Republicans are likely to control at least one chamber of Congress.

In other words: Even if the Court overreaches on abortion and forfeits its popular support, the conservative judicial project is likely to endure. And given Roberts’s current poll numbers, it’s not even clear that Roe’s invalidation will durably erode public reverence for the judiciary.

No matter how events unfurl from here, Roberts has already established himself as the greatest Republican politician of his generation. No other conservative has managed to realize as many of the movement’s ideological goals at so little political cost. And if you don’t think that Roberts can be fairly described as a politician, well, that only confirms the enormity of his achievement.