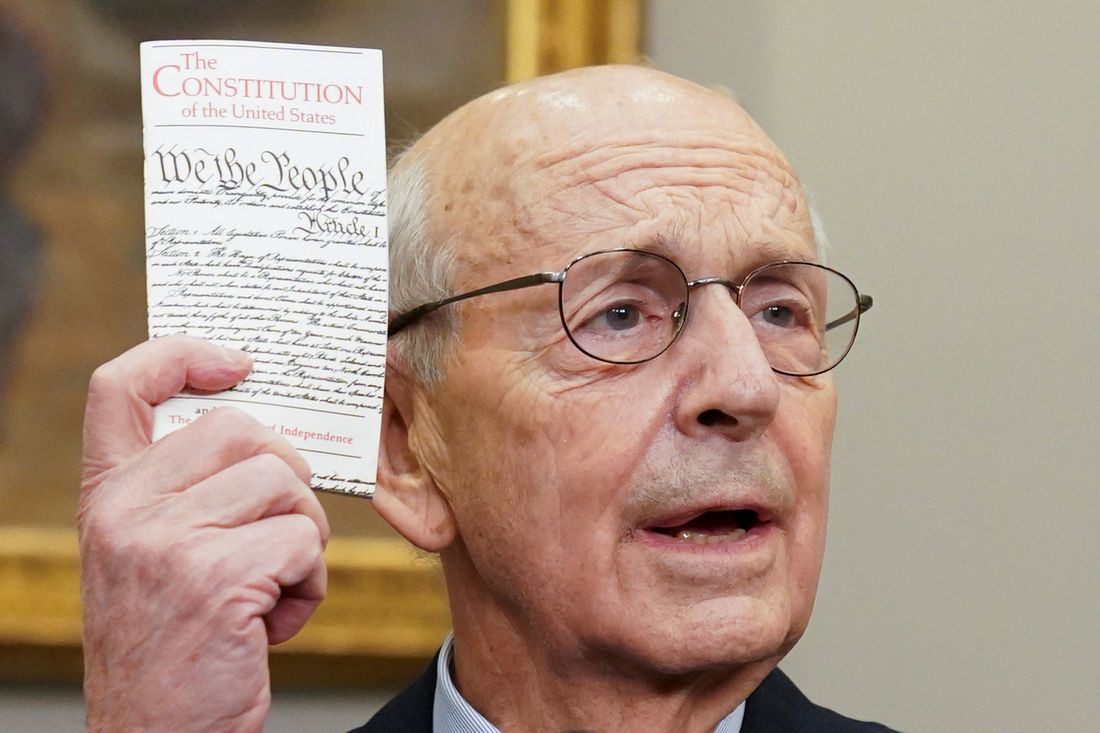

Toward the end, you could hear it in Stephen Breyer’s voice. His meandering questions in oral argument could often telegraph exasperation, the sort you get from a man convinced of the loftiness of his own intelligence, but lately that had given way to incredulity. Listening to conservative arguments that once would have been deemed beyond the pale of the Supreme Court, Breyer “on occasion just holds his head,” reported NPR’s Nina Totenberg.

He retired because he knew the clock was ticking on Democratic prospects of filling his seat with a liberal; he retired because he is 83 years old. But Breyer also may well have retired because the self-styled consensus builder found himself on a Court with few takers. The man who declared in 2020 that “a dissent is a failure” was increasingly left with not much else to do.

Whoever succeeds him will not only carry the burden of being the first Black woman on the Supreme Court, as President Biden has promised. The future justice will also have to figure out which path to take as part of an ideological minority for years, maybe decades, to come. None of the choices are particularly appealing.

It’s clear what road Breyer took, but in today’s Court it looks like a dead end. The conciliatory posture he and Elena Kagan, a fellow pragmatic moderate, most often chose “made sense in a 5-4 Court when all you needed to do was peel off one vote from a wobbly conservative” like Anthony Kennedy or John Roberts, says NYU law professor Melissa Murray. “That’s not where the Court is now with a 6-3 conservative supermajority, where Roberts’s vote is unlikely to be determinative. That shift in composition means that there’s an existential question about the role of consensus builders. Can there be a consensus where the only consensus is what the supermajority wants?”

The virtues of deal-making are easily overstated. Legal insiders tend to cherish compromises because they burnish the Court’s image of impartiality. Court chroniclers like them because horse-trading and arm-twisting create suspense, involve characters, and feature a story line other than “conservatives steamroll their agenda; liberals dissent.” The Court could have come to a consensus on pre-Trump cases like Bush v. Gore and Citizens United, but the conservative majority powered ahead anyway in 5-4 decisions.

Surprises have happened. But the compromises for which Breyer is credited now look at best like temporary attempts to stanch the bleeding. In 2012, Chief Justice Roberts initially sided with the conservative justices in the private, post-argument conference to strike down the individual mandate of the Affordable Care Act and to uphold its Medicaid expansion, putting him in the majority on both fronts. Eventually Roberts changed his mind, deciding that the mandate was actually a constitutionally appropriate tax but that the Medicaid expansion was coercive. Breyer and Kagan had previously voted to uphold the Medicaid expansion as is, Joan Biskupic reported in her biography of Roberts. “But they were aware that Roberts was now making a concession on the individual mandate, and they were open to compromising.”

When Kagan and Breyer voted to let states opt out of the expansion — Ginsburg and Sotomayor dissented — the assumption was that red state governors would take the free money. Instead, 2.2 million low-income adults are left uninsured in the 12 states that still refuse to expand Medicaid. The individual mandate, killed by Trump’s tax bill five years later, turns out not to have mattered that much anyway.

Biskupic also wrote in another book that, in 2013, Kennedy came close to striking down the University of Texas at Austin’s affirmative-action plan until Breyer convinced him to punt, avoiding a fervent Sotomayor dissent and serving to “lower the temperature of the negotiations.” Two days before word leaked of Breyer’s retirement, the Court agreed to revisit campus affirmative action, and this time it seems poised to strike it down.

At best, Breyer helped keep alive these policies, and the constitutional interpretations that underpinned them, for just under a decade. The same was true of his opinion striking Nebraska’s so-called partial-birth abortion ban in 2000, an opinion you might have heard about for its measured sensitivity to the anti-abortion position. That one lasted seven years: Samuel Alito replaced Sandra Day O’Connor in 2006, and a national version of the ban was promptly upheld.

To Breyer’s credit, his technocratic opinions knocking down spurious restrictions on abortion clinics got votes from Kennedy in 2016 and then Roberts in 2020. The second case came during the relatively halcyon days when Roberts was in the majority in 97 percent of the term’s cases, according to an analysis by Adam Feldman. At the time, Brett Kavanaugh was getting his bearings and Ginsburg was still alive. But this term, the conservatives in the majority have allowed most abortions to be banned in Texas without explicitly saying they’re overturning Roe v. Wade, and by this June, the end of Breyer’s last term, they will almost certainly make it official.

Can you blame Breyer and his fellow traveler Kagan for attempting compromise while it was possible? Well, yes, argue law professors Micah Schwartzman and Nelson Tebbe, who published a scathing law-review article on these justices’ strategy of splitting the difference with conservatives on cases concerning the separation of church and state, which they termed “appeasement”: an offering of “unilateral concessions for the purpose of avoiding further conflict, but with the self-defeating effect of emboldening the other party to take more assertive actions.” Schwartzman told me, “Whatever case you might have made for it as a consensus-seeking strategy was undermined when Justice Ginsburg died. It’s hard to see that model having a future.”

Before her death during the waning days of the Trump administration, Ginsburg, herself a consensus builder earlier in her career, had chosen a different path from Breyer. She spent much of her time in straightforward dissent, grabbing public attention by reading her dissents aloud from the bench. The final years saw her tag-teaming with Sotomayor as a leftward bloc on many contentious cases.

Now poised to be the senior justice in what looks to be an all-female liberal minority, it is clear how Sotomayor sees her role: as the moral conscience of the left. Before she was nominated, Sotomayor had been criticized, including by allies of future Justice Kagan, as incapable of wielding the powers of intellectual persuasion — of “gently but firmly persuading a bunch of prima donnas to see things her way in case after case,” as Harvard’s Laurence Tribe put it in a private letter to Barack Obama. Another way of looking at it, says George Washington law professor David Fontana, is that Sotomayor was “the people’s justice,” and Kagan the “Establishment’s justice,” at a time when the Establishment has never been less influential on the Court. Even Kagan sounds pretty fed up these days. Says Fontana, “She both reflects and reinforces a progressive legal Establishment that has become more bewildered with the Supreme Court.”

If they are bewildered, it’s because the Court’s right has stopped pretending that they are there to call balls and strikes, or adhere to the originalist interpretation of the Constitution, or do anything but accomplish long-held ideological goals. Barring some unforeseen shift, there isn’t much the liberal minority can do except tell the truth about that.

More on stephen breyer

- Can Kamala Harris Break a Tie on a Supreme Court Confirmation?

- Democrats Are Playing Catch-up on Supreme Court Nominations

- Will Sinema and Manchin Screw This Up?