Dating back at least to the Eisenhower administration, most Republicans insisted on federal voting-rights laws to protect nonwhite citizens against discriminatory state-government actions. Their opponents, mostly southern Democrats, argued that state prerogatives over voting and elections should be inviolable and that racial discrimination was either nonexistent, exaggerated, or nobody else’s business. Today, we see these same arguments being made against voting-rights legislation — but they’re coming from the party that vehemently opposed them not long ago.

While the Democrats’ inability to enact filibuster reform understandably draws a lot of attention, the more fundamental reason for Congress’s inability to enact voting-rights protections is the Republican Party’s lockstep opposition to any new legislation on the matter. It’s no surprise that the GOP rejected the wide-ranging provisions of the For the People Act, which gets into issues like public financing and gerrymandering reform. But another bill Democrats are trying to enact, the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, really just restores elements of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that most Republicans used to support routinely.

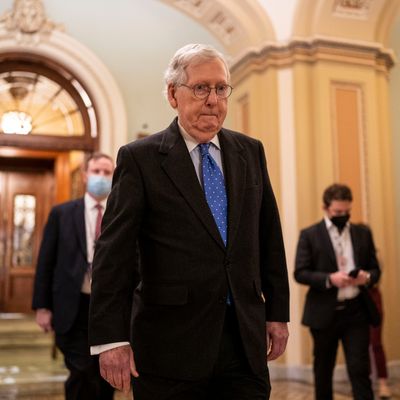

The leading Republican arguments against this legislation have been neatly summed up by Mitch McConnell. The Senate minority leader has expressed outrage over the idea that the Voting Rights Act enforcement mechanisms struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013 might be restored — though he had voted twice (in 1986 and 2006) to extend the 1965 law with those provisions intact.

In a speech on the Senate floor last June, McConnell described the relatively modest John Lewis bill as some sort of radical power grab by Democrats. “What they are trying to do directly with H.R. 1 [the more sweeping For the People bill] they would try to achieve indirectly through this rewrite of the Voting Rights Act.”

The John Lewis bill is actually only a “rewrite” of Sections 4 and 5 of the 1965 law. Section 4 laid out a formula for identifying jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination in voting; Section 5 required pre-clearance by the U.S. Justice Department for election- and voting-law changes in states, cities, or counties that met the criteria. In Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court deemed Section 4 unconstitutional in its current language, effectively neutering Section 5 as well.

Technically, McConnell was correct when he asserted on the Senate floor that “the Supreme Court did not strike down the Voting Rights Act; it’s still the law.” But by striking down Section 4, the Court robbed the law of its power by removing its central enforcement mechanism.

Later in his speech, McConnell claimed, incorrectly, that the Supreme Court had “concluded that the conditions that existed in 1965 no longer existed. So there is no threat to the voting-rights law. It’s against the law to discriminate in voting on the basis of race already. And so I think [new legislation] is unnecessary.” This suggestion that racial bias in voting practices is a thing of the past is in line with extensive public-opinion research showing that rank-and-file Republicans now believe that discrimination against white Americans is as prevalent — or perhaps even more prevalent — than racism against nonwhite Americans.

But what the Court actually held, in its 5-4 decision, is that the Section 4 formula based on 1965 data was outdated; the majority did not declare that racial discrimination in voting and election laws no longer exists. This is a crucial distinction. The Court basically invited Congress to update the formula if it chose to do so, and that’s precisely what the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act is intended to do. Refusing to do so is the power grab.

When asked, at a press conference later in June, why Republicans were blocking a voting-rights bill from being debated, McConnell answered, “This is not a federal issue. It oughta be left to the states. There’s nothing broken around the country.” So the GOP leader has also explicitly embraced the states’ rights argument that defenders of discrimination used against the original Voting Rights Act.

We’ve come a long way since 30 of 31 Republican senators voted for the Voting Rights Act in 1965, and since every Senate Republican voted for its extension in 2006. And it’s not just support for or opposition to legislation that has changed: The state-sovereignty claims and dismissals of racism advanced by Jim Crow Democrats fighting civil-rights and voting-rights legislation in the 1960s have now become orthodoxy for the party of Abraham Lincoln.