More people are dying right now on a per capita basis in Hong Kong than have died in any country, save one, at any point in time, save one, during the entire two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has globally taken, all told, at least 15 million and possibly 20 million lives.

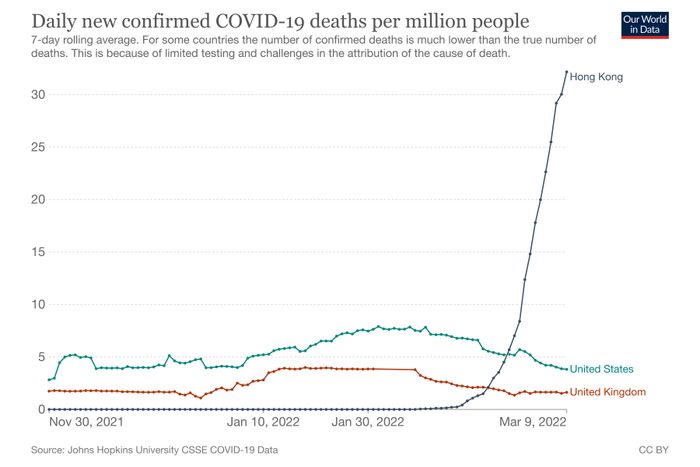

In Hong Kong — often celebrated as a pandemic success story, now boasting better vaccination rates than the U.S. — the seven-day average of per capita deaths from COVID is about to surpass Peru’s world record from April 2021, before that country had access to vaccines, according to Our World in Data. On a per capita basis, Hong Kong’s Omicron wave is already deadlier than the U.K.’s winter surge, often described as the worst period experienced by any OECD nation during the pandemic, and more than twice as deadly as America’s winter surge a year ago.

The comparison is a bit misleading: The famously dense “special administrative region” is much more like a city than a country, and its present death toll, while terrifyingly high, has not reached the heights of New York City in April 2020, among other especially hard-hit metropolises. But because new cases there are only now appearing to peak and the chart of new deaths is still practically vertical, the Hong Kong numbers are almost certain to grow — possibly by quite a lot. If the typical lag holds, the new daily death toll may continue to rise for weeks and could easily double.

This experience is quite discordant with the state of COVID discourse in the United States, where CDC director Rochelle Walensky recently described the possibility of future surges, dismissively, as “annoying.” Even those who argue that we’re letting our guard down too quickly are primarily focused on preparing for the next wave and variant, not responding to the dying vestiges of the last ones. But the fact that the Hong Kong surge seems to be unfolding in almost another pandemic universe than ours is not to say that the brutality of the surge is inexplicable or even mysterious. The vulnerability of a population to a new variant is the result of not just the variant’s virulence but also the immunological profile of the community. This is among the reasons why death rates in the United States, through both Delta and Omicron, were so much higher than its “peer” countries in Europe.

And while Hong Kong does boast relatively strong overall vaccination numbers, those top-line numbers obscure the most important factors, as they always do. Because vulnerability to severe disease and death skews so dramatically by age, with those over 80 more than a hundred times likelier to die from COVID-19 than those in their 30s, overall mortality risk is more a reflection of how well the elderly are vaccinated than how well the population as a whole is. In Hong Kong, they are not very well protected at all: Forty-five percent of Hong Kong seniors are vaccinated, and only 15 percent of those in old-age homes are, which, in a population under 8 million, left more than half a million people over the age of 70 unvaccinated when Omicron arrived.

Perversely, Hong Kong is more vulnerable now because it did so well before. Success in containing disease spread until Omicron meant there had been much less exposure to COVID-19, and much less of the “natural” immunity that results, than in parts of the world where it has been infecting people somewhat steadily for two years. In 2020 and 2021 combined, The Wall Street Journal reported, Hong Kong had a total of 13,000 cases and 213 deaths; during Omicron, the totals are 500,000 and 2,365. This may help explain why mainland China is engaging in 2020-vintage suppression tactics, including severe lockdowns, as much of the rest of the world has begun to move on: So many fewer people getting sick over the past two years means many more might get very sick now.

Not that widespread exposure is a panacea. It is easy to forget now, but Anthony Fauci spent most of 2020 estimating that somewhere between 60 and 70 percent of Americans would have to be either infected or vaccinated to reach herd immunity. That dream — of total disappearance of the disease — is now a distant memory, of course. But we long ago hit those benchmarks, along with higher ones he set beginning in late 2020, with estimates that 90 percent or more of the country has been exposed to the disease, through vaccination or infection, even as a thousand or more Americans have been dying every day for six months.

This is all to say that we are all living in a different pandemic landscape now with new variants armed with novel immune-evasion capacity, a clearer sense of the limitations of vaccines in preventing spread, and a growing understanding of the dynamics of waning immunity. To judge from the recent Omicron experience in Europe, weathering another surge without much disruption or dying may require that vaccination levels and regular boosters among the elderly get pretty close to 100 percent. The U.K. managed Omicron relatively well with only 71 percent of its overall population double-vaccinated but 93 percent of its seniors. More than half of the country as a whole has gotten boosted compared with just 29 percent in the U.S. This is partly why recent data from the U.K. is a bit more curious than that coming from Hong Kong. There, over the past few weeks, hospitalizations have begun to grow steadily in all regions of the country after a post-Omicron lull. The growth isn’t huge — 21 percent week over week — but it is visible everywhere.

The explanations are not so obvious — a reminder that, more than two years into this pandemic, there are still things about spread dynamics we don’t understand. At first, given low case levels, the rise in hospitalizations was attributed by some analysts to waning booster effects among the elderly many months after that rollout began. But there does not seem to be a clear sign in seroprevalence data that antibodies are declining at the moment. Behavioral changes may be playing some role with the recent lifting of Omicron restrictions, but case growth does not seem to be concentrated in any subgroup. Instead, it appears consistent across all age groups and regions. And while the Omicron sub-variant BA.2 has been growing as a proportion of British cases for a while now, presently accounting for more than half of new cases, it is not creating a major new wave of cases, and there are few clear signs it produces meaningfully different outcomes than the original Omicron, BA.1. A final hypothesis says hospitals are simply picking up more incidental COVID; having resumed normal operations post-Omicron, more people are coming to the hospital for other kinds of procedures, and some percentage of them are popping up as positives. (This would explain the lack of a lag between case growth and hospital growth.) But even isolating those cases, admissions for COVID are ticking up, too, if by a smaller degree. And it’s not just the U.K.: caseloads across Europe are beginning to grow.

As a result, many of those looking closely at the British turn are shrugging in confusion, which means it isn’t easy to extract lessons from the U.K. experience for the U.S. future. (Though one lesson the U.K. is apparently taking is that a fourth shot, or second booster, is important.) It is worth keeping in mind that this upturn is still recent and relatively small compared with the heights reached during Omicron (though in the southwestern U.K., more patients are now being admitted to hospitals with COVID-19 than at any point in the past year). But for those who’ve assumed the pandemic would steadily peter out, requiring a collective decision to declare “It’s over” — well, these are signs that the future is likely more complicated than that.

This does not mean a second Omicron wave — or something potentially worse — will soon come crashing onto American shores. But it does suggest that the more time passes since the peak of that last wave, the less sure we can be that prevalence will remain low and severe disease relatively rare. And we may well see another game-changing variant like Delta or Omicron down the line.

It is still the case that our existing vaccines work well against all variants. And as those promoting the “urgency of normal” have been emphasizing, Americans who’ve been vaccinated three times and boosted relatively recently are remarkably well protected against severe hospitalization and death. But, again, only 29 percent of Americans have been boosted, a good chunk of them now long enough ago that their protection may be on the wane. Given that waning, as well as our very slow rate of new vaccinations and our distressingly low uptake of boosters, we may well find ourselves this spring and summer less protected as a country than we were before Omicron, which ultimately infected probably more than a 100 million people and killed almost 150,000 Americans. That isn’t to say that will all happen again, since so much depends on the nature of the variant and the state of the immunological landscape. But, well, it might. This thing isn’t over yet.