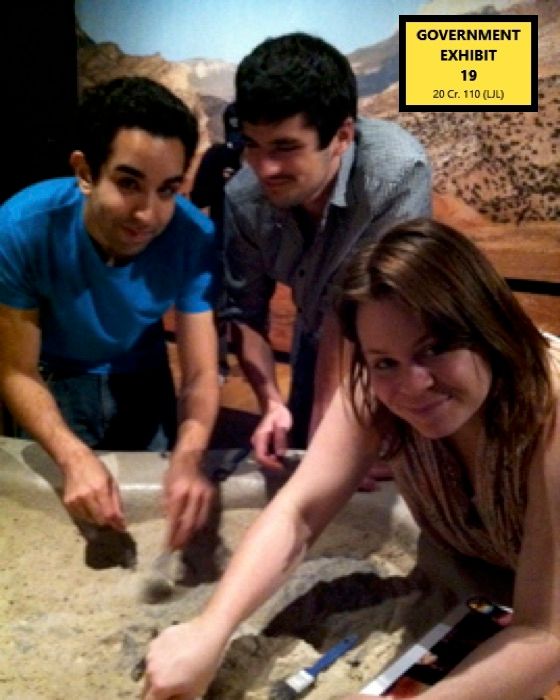

The photo showed three Sarah Lawrence College roommates smiling gleefully on a trip to a museum. Their expressions are easily recognizable — a group of young friends enjoying a day away from campus.

The jury saw that photo of Santos Rosario and his friends on the first day of the trial of Larry Ray, who is accused of verbally, physically, and psychologically abusing a group of his daughter’s former college roommates, and of turning those students into a criminal enterprise that engaged in racketeering and sex trafficking.

By the end of the second day, the jury had heard a recording of Ray ordering Rosario to get on all fours and crawl like a dog across his living room floor.

Not even two years separate that photograph from that recording.

In the first few days of the Ray trial last week in federal court in lower Manhattan, the prosecution’s first job was to make sense of this strange and awful story, as bright-eyed college sophomores become Ray’s miserable disciples.

“When you have cases like this one, it’s really important to reduce the sense of otherness that can happen when people have been victimized as part of a coercive control group,” said Moira Penza, a former assistant U.S. Attorney who prosecuted NXIVM leader Keith Raniere, who last year was sentenced to 120 years for sex trafficking and other charges similar to those faced by Ray.

“There are a lot of people who instinctively think, ‘That could never be me. That could never be my son or daughter. That could never be my friend,’” Penza said. Prosecutors will attempt to break this notion down by showing the jury “how vulnerabilities are exploited, about how it’s a slow creep, about how trust is built at the beginning — about how information that can be used against someone is gathered.”

For Rosario, now 30, it all started with a girl. During his freshman year at Sarah Lawrence, he dated Talia, Ray’s intensely devoted daughter, who raved about her heroic, righteous father. By the time Ray moved into Talia’s dorm sophomore year, she and Rosario had broken up. Still, they remained close friends and Rosario, 19 at the time, looked to Ray, who was then 50, for all manner of advice and guidance.

“I thought he was very cool, very smart, very composed, and very inspirational,” Rosario said, describing the first night he met Ray in 2010. Ray offered him both emotional and physical guidance. Sarah Lawrence students remembered Ray encouraging Rosario to work out, making him and others do push-ups daily. “I ended up confiding in him a lot about issues I had with my family, my depression that I struggled with in high school,” Rosario said.

From there, the relationship quickly became a nightmare.

Rosario’s indoctrination began with Ray forcing Rosario to write and frequently revise dubious confession statements. Ray would accuse Rosario of harming him or others in various ways; Rosario would deny it. Ray would then insult him, attack him, or threaten to abandon him, which would spur Rosario to admit to doing things which, he said now in court, that he didn’t actually remember doing.

“Larry kept insisting I was lying,” Rosario said. “I was convinced that if Larry said it wasn’t true, it couldn’t be true because he’s such an honest man, and he’s been my friend, so I must be confused, and I must be misremembering or I must not want to remember what I did.”

These accusations started small: Ray told Rosario he wasted his time on purpose, or distracted his daughter from schoolwork. But they grew increasingly baroque. The jury heard audio of Rosario confessing under pressure to poisoning Ray and recording their conversations at the behest of a shadowy conspiracy.

They were shown a video in which Rosario’s sister Felicia is sitting on a leather couch in Ray’s living room, rocking back and forth in distress. Rosario is standing over her; whenever she speaks he slaps himself in the face. Ray had instructed him to slap himself every time Felicia spoke, in order to keep her from talking. “Stop talking, Felicia!” Rosario screamed. “I’m no longer going to enable it.”

The prosecution then showed a photo of Rosario with his face so swollen and red that he looked like a different person — the consequence, he explained, of slapping himself repeatedly for over an hour.

Prosecutors presented several long audio clips in which Ray threatened Rosario repeatedly, after accusing him of posting Ray’s address online. Ray picks up a hammer and brandishes it in front of Rosario. “I swear I’ll put this through your skull,” he says. Someone opens a window, and Ray says: “Go out that window,” an order to Rosario, who has told Ray at length about his suicidal thoughts. Gesturing at Rosario and his sister Felicia, Ray suggests, “Why don’t you hold hands and jump together?” Then he begins to hit Rosario’s legs with the hammer. “Be careful,” he growls. “Those legs break really easily.”

Ray eventually began extracting money from Rosario, accusing him of damaging property and demanding repayment. Under pressure, Rosario turned to his parents and friends to cover the tens of thousands of dollars Ray was asking for. This list of debts grew and grew — eventually, Rosario said, the list expanded to include every item he could “conceivably have come in contact with” in the entire apartment, totaling $100,430 in supposed damages.

As heinous as Ray’s behavior may be, his motives are often inscrutable. (Ray has pleaded not guilty to the 17 charges against him.) Why wreak havoc on a college student’s life and convince him that he’s part of a convoluted plot? It will be up to the jurors to consider whether Ray was a sophisticated con artist driven by money and sex, or an irrational actor caught in his own grim conspiracy. In the end, does that distinction even matter? Ray’s defense team seems to think so.

In the defense’s opening statement, Allegra Glashausser, one of Ray’s attorneys, described Ray and his victims not as a criminal enterprise but as a “group of storytellers” who erected around themselves a bizarre, semi-fictional world. It was as if, Glashausser said, they leapt through Alice’s looking glass.

“Through the looking glass, the truth became complicated. At times the storytellers couldn’t separate truth from fiction,” Glashausser said. “That’s the thing about a good story: It makes you believe. And Larry believed most of all.”

In court, Rosario spoke slowly, his voice quavering. Often, long gaps of silence preceded his answers. Speaking in court about Ray, he said, was a stressful experience. Until recently, Rosario seemed to be one of the people least likely to speak against Ray. During our reporting for the article that, after its publication in 2019, spurred an investigation into Ray that eventually resulted in his arrest, we tried and failed many times to reach Rosario. It was unclear whether he was ignoring our interview requests or hiding (whether from us, from someone else, or from everyone, we didn’t know).

Eventually, we visited his parents’ home in the Bronx. When they came to the door, we told them we were writing a story about Ray. The couple was visibly shaken. Through an interpreter, the Rosarios told us that they had not spoken to their son, or his two sisters, in years. They estimated that, between their children, they’d given Ray some $200,000. They paid because their children said they might commit suicide if they didn’t come up with the money. The Rosarios were forced to sell their home to make ends meet.

They appeared heartbroken: After immigrating from the Dominican Republic, they seemed to have achieved the American Dream, sending their children to Sarah Lawrence, Harvard, and Columbia, only to watch all of them disappear from their lives under Ray’s influence.

We did eventually find Rosario in a surprising place — the comments section of the story we published about Ray. Soon after publication, he posted a long comment defending his mentor. (We were able to verify that his email was connected to the username that posted it). “Larry Ray has only ever offered his friendship, attention, and care to me,” he wrote:

“He fed us, never skimping on the quality or healthiness of meals. He offered a listening ear, always making himself available to us, no matter the time. He taught us about and exemplified the notions of honesty, integrity, honor, and compassion. He encouraged us to enhance and educate ourselves, constantly suggesting that we read all kinds of books ranging from philosophy, history and current events, to science and mathematics … Without a doubt, I owe whatever independence, clarity, emotional balance, and resilience I have to Larry Ray and the time that I have spent with him.”

The comment certainly seemed to indicate that he remained under Ray’s influence. According to the prosecution, he was — the government entered that comment into evidence during pretrial litigation and said Rosario had written it under pressure from Ray.

How does someone seemingly so devoted to Ray, and for so long, suddenly become a star witness in the case against him? How does someone apparently so coerced find their way to a new truth? That’s what the jury will be asking as they make their way through the early stages of this case.

After Rosario finishes his testimony, prosecutors will try to show a similar pattern in Ray’s treatment of the other two students in the picture at the museum, Dan and Claudia, and of Rosario’s two sisters, Yalitza and Felicia.

“What you’re trying to do is have one witness’s testimony corroborate the other witness’s testimony,” said Penza. “Wherever you can show that the same behaviors were being used over and over again, that’s going to be persuasive to a jury.”

Even in court, Ray shows signs of still wanting to be in control of the story. The other morning, before Judge Lewis Liman called the jury into the 24th-floor courtroom, he had a message for Ray.

“At various points yesterday during the testimony of the witness, my staff observed Mr. Ray either nodding in approval or shaking his head in apparent disapproval of what the witness was saying,” Judge Liman said. “I’m prepared to assume for now that that was just reactions in the heat of the moment. That assumption is not going to last into today.” The caution seems to have been effective.