As we speed toward this summer’s Supreme Court ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, and with it the likely overturn of Roe v. Wade, there is a lot of bad news coming from states rushing to pass ever-more-totalitarian restrictions on those who seek abortion care.

Following the lead of Texas, which last fall passed a six-week ban that deputizes citizens to sue anyone who helps a patient get an abortion, Missouri Republicans in March proposed a law that would authorize citizens to sue anyone who assists a person traveling out of state to terminate a pregnancy.

And as if Republicans’ creative decision to sample the Fugitive Slave Act wasn’t chilling enough, April began with the sudden and terrible passage of a near-total ban on abortion in Oklahoma, one that would put abortion providers at risk of a ten-year prison sentence. The law is an especially gutting blow since Oklahoma was the state that, since September 2021, had been the primary refuge to those abortion seekers able to make it out of Texas.

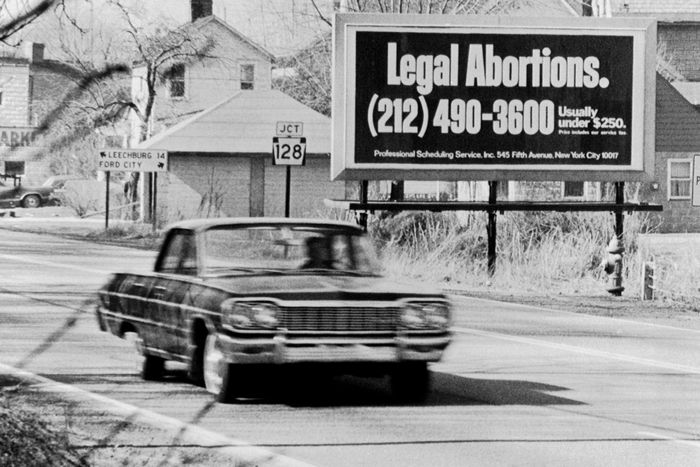

Oklahoma is among the 21 states that, according to the Guttmacher Institute, have laws that could be used to restrict the legal status of abortion as soon as Roe falls. Some of those laws date back to before Roe was decided in 1973; others have been crafted in anticipation of its expected reversal. Many of these states are grouped together in the South and Midwest, creating a geographic nightmare for people who need abortion care. Every single state that can preserve its access will become a crucial destination.

In the chaos of this imminent and inhumane catastrophe, it’s been pretty hard to find political leaders who have any fresh ideas about how to proceed. An exception may be Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer, who on April 7 announced that she was doing something new — something aggressive, risky, and proactive — about protecting abortion access in her big and important midwestern swing state.

Michigan still has in place a law criminalizing all abortions except in cases in which the mother’s life is in danger. The law was enacted in 1931, though Roe has overridden it since 1973. So if Roe is significantly weakened or struck down, Michigan would join the oppressive block of midwestern states in which the procedure would become unavailable.

But Whitmer is asking her state’s highest court, by means of a lawsuit, to recognize a right to abortion under the Michigan Constitution. What’s more, in order to do that, she is invoking a power available to Michigan governors called the “executive message,” which, she believes, will force the State Supreme Court to take the question of the constitutionality of abortion out of the trial and appeals courts and issue a decision on it as soon as possible.

Whitmer’s suit claims that the 1931 law is unconstitutional because it runs afoul of Michigan’s due-process clause by violating the right to privacy and bodily autonomy — a state-level recapitulation of the legal argument behind Roe. She is also claiming that the criminalization of abortion violates the state’s Equal Protection Clause since the 1931 law was intended to reinforce antiquated assumptions about women’s legal rights. That law, Whitmer told me over the phone, was written “to control women and ensure that we didn’t have full autonomy over our own bodies, and it’s time for it to go.”

It is unclear whether her tactic will work. The Michigan Supreme Court, which is 4-3 Democratic, could find a way to punt the suit until after the election, making its decision less politically electric. And when it does rule, there’s no sure bet that it would decide in her favor. But in her enterprising play to ensure that abortion will remain legal in Michigan in a post-Roe world, Whitmer is at least showing gumption, unlike the many Democrats at the federal level who have so far proved themselves feckless in the fight for reproductive-health-care access. For decades, the party’s craven approach to the steady erosion of abortion access has stood in contrast to the right wing’s patient, crafty, multipronged strategy.

Republicans have spent the years since Roe working every angle: taking over state legislatures, building a pipeline of anti-abortion judges who have risen to the highest courts in the country, gerrymandering districts and disenfranchising Democratic voters and ensuring that presidents elected by a minority of Americans have now appointed the majority of Supreme Court justices.

All this — this willingness to break and twist every rule, to proudly capitalize on the diabolical inequalities built into our system — has been done in the same years that Democrats have repeatedly chosen not to make abortion access a centerpiece of their campaigns or their rhetoric. They have behaved as if Roe were sufficient (when it was not) and that it would not really fall (when it will) and that even if it might, the right to full reproductive medical care was too icky and dangerous to get really close to, let alone embrace as a morally compelling fulcrum of their work.

Whitmer emphasized that her approach was made possible and necessary by the particular dynamics of her state, where Republicans control the legislature and a Democrat sits in the governor’s mansion. Fifteen states, plus the District of Columbia, most of them led by Democrats, have passed laws that will protect abortion in those states even absent Roe. Other states with so-called trigger laws already on the books or in the works are run by conservative governors and have conservative legislative and judicial branches, making this kind of strategy impossible. Then there are the special provisions of the Michigan Constitution that permit Whitmer to sue and invoke the executive message. “Not every governor has these tools,” she said.

Still, she is taking an enormous risk in a state where violent partisan tempers are running as high as anywhere. Whitmer, who is up for reelection this year, announced her lawsuit on the fourth day of jury deliberation in the prosecution of four men who are alleged to have plotted to kidnap her in 2020. While claiming not to have followed the trial closely, she acknowledged that the case — in which the men allegedly surveilled her vacation home and may have planned to shoot her security detail and leave her stranded by herself in a boat in the middle of Lake Michigan — “obviously does impact me. I am a person, an ordinary person in an extraordinary job, serving at an extraordinary moment,” she said. On April 8, a jury acquitted two of the accused men and deadlocked on the charges against the two others.

Through a purely political lens, Whitmer’s tactic here is bound to gain her the attention of both the national media and donors. She is betting on a proposition that reproductive-rights and justice activists have long been screaming at the Democratic Party: that abortion is a winning issue.

“I know there will be some that have a strong reaction,” she said. “But I can tell you that the vast majority of people support a woman’s ability to make her own decisions. Women from all parts of the state, from all political perspectives, have relied on and utilized these rights. So I anticipate that we will have broad support.”

What Whitmer is doing here is propellant; it’s energetic. “I’m excited,” she told me. Whether or not her plan works, that stance is going to become ever-more urgent in the months and years to come, since decades of Democratic complacency risk fermenting into a kind of paralyzed despair. That would be the worst outcome in a world in which state-level elections matter more than ever. “The scariest thing,” Whitmer said, “is not taking action.”