Another big COVID-19 wave, fueled by more-transmissible BA.2.12.1 and BA.2 subvariants of the Omicron strain, is definitely under way in the United States. CDC data indicates that at least 86 percent of Americans now live in communities where there is high COVID transmission, up from 72 percent the previous week and 57 percent the week before that. At least 95 percent of Americans now live in areas where there is substantial transmission; only one percent live in communities where the transmission is estimated to be low. It’s the fifth time one COVID strain — or in this case two subvariants — has generated a large wave of cases in the U.S. as well the country’s sixth or even seventh overall wave of infections since the pandemic began.

But this wave of new infections is significantly larger than official case counts suggest, since many if not most cases are either being detected using at-home tests that are never reported or are asymptomatic and not being detected at all. As the Washington Post pointed out last week, nobody actually knows how big this new COVID wave is right now; COVID experts suspect the number of new cases in communities across the U.S. is actually five to ten times higher than official counts indicate. “Any sort of look at the metrics on either a local, state, or national level is a severe undercount,” Pandemic Prevention Institute epidemiologist Jessica Malaty Rivera told the Post. Scripps’ Dr. Eric Topol wrote a week ago that there are likely at least half a million new infections happening every day, making this new wave the second largest to strike the country. And it’s been under way for a while.

To be clear, while COVID hospitalizations are again rising in parts of the country — to the extent that the CDC is escalating its warnings to the public and expanding both eligibility and the strength of its recommendations for booster shots — there is not yet any indication that this new wave, by any metric, will reach anywhere near the overwhelming proportions of the Omicron-fueled fourth wave over the winter or that the Omicron subvariants infecting Americans have evolved to cause more severe illness than previous strains. (Whether or not the world is as lucky with the future variants and subvariants that evolve is anyone’s guess.)

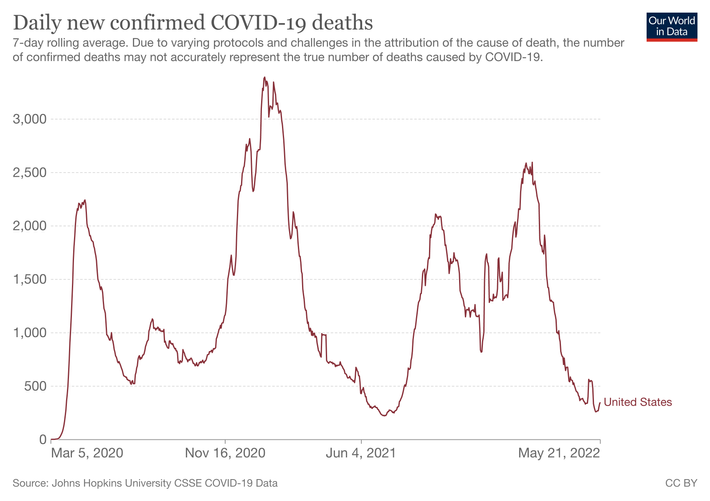

Most important, while the COVID death rate always lags behind new cases and hospitalizations, fewer people are now dying from COVID-19 in the U.S. — an average of 350 each day as of this weekend — than at any point since last summer’s pre-Delta-variant lull. Though they arguably remain underused, we now have powerful weapons, like the COVID antiviral Paxlovid, to combat severe illness that we didn’t have then. And there are other COVID treatments, at-home tests, and high-filtration face masks like N95s, which provide meaningful one-way protection against COVID transmission, that are far more widely available now as well.

But nothing good has ever come from another big wave of COVID infections. And this wave is rising at a time when countless Americans have concluded (and are behaving as if) the pandemic is over. The new wave is also rising as many politicians and public officials at every level of government have largely abandoned interventions aimed at curbing the spread of COVID. Dr. Topol has aptly described this ongoing failure, which includes Congress refusing to adequately fund the U.S. pandemic response moving forward, as “the COVID capitulation” — and there is no end to it in sight. It has been clear for months that Americans are more and more on their own when it comes to avoiding COVID. Don’t count on the return of mask mandates or “stop the spread” initiatives or more yard signs professing the need to protect essential workers. The pandemic isn’t over, but the U.S. pandemic response continues to steadily wind down.

In addition, despite some meaningful improvements over the past two-plus years, public-health authorities continue to struggle to clearly and effectively communicate COVID warnings and public-health messages. The CDC’s current face-mask recommendations, for instance, are linked to health-care system capacity, not to the level of community transmission (and even so, the CDC currently says that nearly 50 percent of Americans now live in places with high enough risk that they “should consider” wearing a mask in public indoor places).

The U.S. wave is also being fueled by at least one subvariant, BA.2.12.1, that seems to be able to reinfect people who were previously infected with the original Omicron strains (BA.1 and BA.1.1) just months ago. As of the week ending May 14, the CDC estimated that 47.5 percent of new U.S. COVID infections were from the BA.2.12.1 variant, which means the next round of data will likely indicate the subvariant has become the dominant COVID strain in the country, beating out BA.2, which had itself become dominant by the end of March. And the Omicron subvariants, each with their own unique advantageous mutations, are still coming: BA.4 and BA.5 are circulating in the U.S.; it remains to be seen if they will be more dangerous than BA.2.12.1.

Furthermore, thanks to waning immunity and low booster uptake, 60 percent of American seniors may now lack adequate protection against severe illness from COVID-19, according to CDC director Rochelle Walensky. Last week, she highlighted in a public meeting that there has been “a steep and substantial increase in hospitalizations for older Americans” — including a 25 percent rise among people 70 and older from the previous week. She also noted that just 43 percent of Americans 65 and older have received a dose of COVID vaccine in the past six months. Among seniors (and all U.S. demographics), the uptake of booster shots — which provide meaningful additional protection from severe illness and death — trails other comparable nations by a significant margin. Half of the unboosted Americans surveyed earlier this year by the Kaiser Family Foundation said they would either never get boosted, or only would if it was required.

There is currently no timetable for when new vaccines tailored to better target the Omicron lineage may become available in the U.S., though there is at least some ongoing debate about how necessary they are in the near term. There is also no timetable for the arrival of intranasal COVID vaccines, which scientists say could offer potentially superior protection in the mucus membranes where the virus enters the body and the infection actually starts. Meanwhile, further spread of COVID, in the U.S. and globally, means more opportunities for SARS-CoV-2 to evolve, and it’s always a roll of the dice whether that leads to mutated strains that are better or worse at infecting us and making us really ill. The fact that we have already seen so many waves from COVID strains which have quickly dominated the globe, each more transmissible than the last, in less than two and a half years does not bode well for what’s to come, particularly when the newest Omicron subvariants are already reinfecting people who had Omicron. And there are other built-in risks to further waves, like the still-murky threat of developing long COVID, the possibility of recombinant strains, additional economic disruption, domestic political consequences, and further hardships and more dangerous health outcomes determined by comorbidity, age, race, ethnicity, and/or class.

The U.S. recently surpassed 1 million confirmed deaths from COVID, and the full total is undoubtedly much higher when including other preventable deaths that happened as a direct result of the pandemic. Though other countries, like India, have lost more people to COVID-19, the U.S. leads the world in confirmed (recorded) COVID deaths. Those million deaths in part prompted this sobering thought in a recent Associated Press article: “The sheer numbers of deaths from preventable causes, and the apparent acceptance that no policy change is on the horizon, raises the question: Has mass death become accepted in America?” It’s a good question and one a lot of Americans probably already know how to answer.

This post has been updated.