“I am a gay guy with an interracial family that won a Trump district. I don’t have the luxury of ignoring people or telling them I know better,” Sean Patrick Maloney says. “I’ve got to listen to what their priorities are and go to work. I’ve won seats five times that way.”

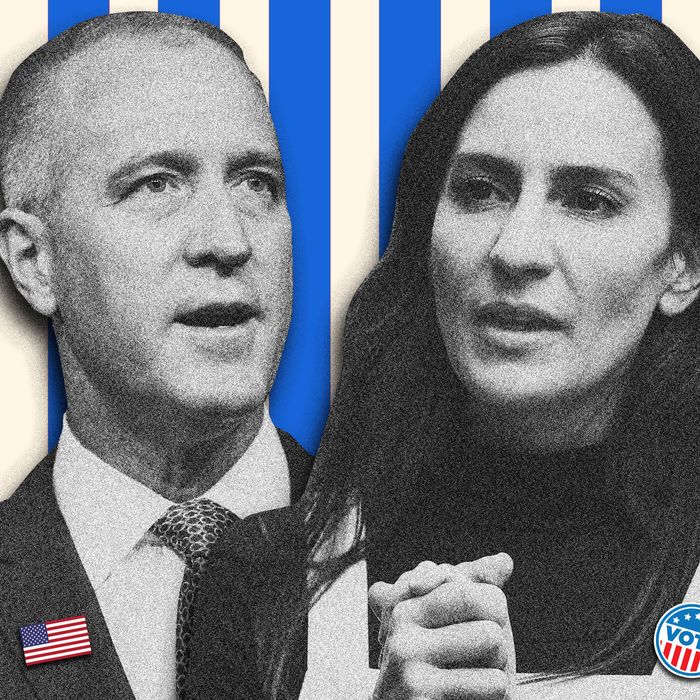

The 56-year-old congressman, speaking at an early voting event in Peekskill, New York, was a little more than a week away from his showdown with Alessandra Biaggi, a young state senator committed to ending Maloney’s career. It has been one of the more contentious primaries of this bizarre election cycle, morphing into a bitter proxy war between centrists and progressives with Biaggi, 36, taking up the cause for the young left. The two are running in the new 17th Congressional District, a seat encompassing Dutchess, Rockland, and Putnam counties. The area, in the past, has been hospitable to progressives and moderates alike, making this contest all the more intriguing. Whoever wins will likely face a competitive general election against the eventual winner of the five-way Republican primary — given the district’s slight Democratic advantage.

Maloney is the heavyweight of the race as chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. He has far outraised Biaggi, banking several million dollars, and has been the recipient of aggressive outside spending from the city’s police union, which has unloaded more than $400,000 against Biaggi, a strong supporter of criminal-justice reform. Maloney has racked up prestige endorsements from Bill Clinton and the New York Times editorial board, cementing his status as the front-runner heading into Election Day on Tuesday. The Times endorsed him in part because of the belief, in political circles, that he’d be the stronger general-election candidate.

But Biaggi, an energetic campaigner, has her own case to make. “I want to be able to fight for the people of New York and the people of this district in the same way that I fought in Albany, because I really feel like there is a void and lack of leadership that needs to be filled with people who actually want to do the job,” Biaggi says, sitting at a Nyack café in the shadow of the Tappan Zee Bridge. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the Working Families Party are in her corner. Mondaire Jones, the progressive congressman who represented many of the areas in the district, steamrolled a field of moderates when he ran in 2020.

Democratic activists in the district are still bitter that this race is being run at all. Maloney technically lives in the 17th, but it was Jones who had, through the counties he represented, the best claim to it. After a state court ruled during the redistricting process earlier this year that Democrat-drawn seats were gerrymandered and violated the state constitution, a special master was appointed to rapidly draw new districts. The new map threw long-serving lawmakers together: Jones ended up in a district with fellow progressive Jamaal Bowman. In New York City, Jerry Nadler and Carolyn Maloney (no relation to Sean) were pitted against each other.

Maloney could have chosen to run in a neighboring district, which encompassed much of the territory he had represented for a decade. Instead, he chose the district that contained much of Jones’s turf, albeit the one he now lived in. Jones, a first-term lawmaker, was pressured into deferring to the chair of the DCCC and a close ally of Nancy Pelosi. After considering a run against Bowman, Jones moved to Brooklyn, where he’s fighting for his congressional life in the newly redrawn Tenth District. “Sean Patrick Maloney did not even give me a heads up before he went on Twitter to make that announcement,” Jones fumed in May. “And I think that tells you everything you need to know about Sean Patrick Maloney.” Ritchie Torres, an Afro-Latino representative in the Bronx, accused Maloney of “thinly veiled racism.”

“One of the ways he has failed New York is by abandoning District 18 and running in 17 and pushing out a young, important voice in this party that is still a rising star who matters to changing the dynamic of Washington, because he wanted an easier district to win,” Biaggi says. “That is what represents, I think, the worst of politics. We’re not kings and queens. We are elected by the people to represent their best interest.”

Maloney has pushed back against the belief that his old district became tougher after redistricting but admits that the situation with Jones could’ve been addressed differently. “I could have handled things better, and I’ve told that to Mondaire,” he says. “But at the end of the day, let’s remember, when the dust settled, I was the only one who lived in this district. And they put not just my home but my entire county and all of the areas I represent in Westchester currently — and some in Dutchess County as well.”

For progressives, Maloney is almost a caricature of an Establishment-aligned centrist. Before Andrew Cuomo resigned in disgrace, he enjoyed a close relationship with Maloney. Many political observers believe Maloney entered the 2018 race for attorney general at the behest of Cuomo, who was interested in seeing a well-funded candidate from the suburbs siphon off votes from Zephyr Teachout, a progressive and fierce Cuomo critic. Maloney lost the race, but so did Teachout.

As a representative, Maloney has racked up a record that has, at times, drawn the ire of the left. He voted to roll back elements of the Dodd-Frank financial-reform act. He backed the expansion of a fracked-gas facility in his district, angering environmental activists. His DCCC has been under fire for spending big to successfully boost a far-right challenger against Peter Meijer of Michigan, one of the few Republicans who voted to impeach Donald Trump.

On that last criticism, Maloney is defiant. “I understand the concern, and I understand that people have, and will always have, different views on the tactics. But let’s be clear. There’s only one strategic imperative at the DCCC, and that is to keep a pro-choice Democratic majority running the Congress, keep dangerous MAGA Republicans from controlling Congress,” he says, which encompasses his own pitch that he’s more electable in November than Biaggi. “And we are better off today than we were before that primary, because we’ve got a weaker opponent, and we’ve got a very strong Democratic candidate named Hillary Scholten who’s going to win that Michigan Third District. And that’s our job.”

Biaggi has heavily attacked Maloney’s past votes on the Affordable Care Act, claiming that the representative voted alongside Republicans to weaken the landmark legislation, like when he broke with House Democrats to vote to repeal the medical-device tax.

“I have done Democratic meetings with him or forums, and whenever I point these things out, he calls me a liar,” Biaggi insists.

None of this makes Maloney happy. “It’s total bullshit. It’s the kind of thing you say in a campaign,” he shoots back. “All of those votes were in the spirit of saving the ACA and making it work better. I’ve voted more than a dozen times since then to support the ACA, to expand the ACA.”

Biaggi is no stranger to slaying centrist Democrats who vastly outspend her. In 2018, she ran as an insurgent against Jeff Klein, the state senator who led the Independent Democratic Conference in Albany, a bloc of dissident Democrats who helped keep Republicans in the majority. With the help of Ocasio-Cortez and most of the city’s activist class, Biaggi won and went to Albany as an unapologetic progressive, where she backed causes like strengthening tenant laws and bringing single-payer health care to New York. An attorney who once worked for Cuomo, Biaggi emerged as one of his most steadfast opponents in the state legislature, and his downfall was, undoubtedly, a victory for her and her allies in Albany.

If there are echoes of AOC’s stunning upset over Joe Crowley in Biaggi versus Maloney — another young progressive woman attempting to defeat an older male representative who ranks high in the delegation — there are significant differences that may make Biaggi’s quest much tougher. Most of Biaggi’s district lies in the Bronx, meaning the 17th isn’t any more familiar to her than it is to Maloney. Her politics may sell well in the suburban counties, or they may not. In 2020, she supported the “defund the police” movement, and Maloney — as well as the Police Benevolent Association — is happy to remind as many voters as possible. Lately, Biaggi has endured criticism from ex-staffers who say her harsh treatment of them contradicts her empathetic image to voters.

And Maloney himself is no Crowley — when it comes to sheer politicking at least. He has won competitive elections in swing districts before, whereas Crowley won his seat by acclamation after his mentor retired. Crowley spent much of his tenure in suburban Virginia, where he owned a house and his children went to school. Maloney is battle-tested and taking Biaggi’s challenge seriously. If Biaggi pulls off the upset, it won’t be because Maloney barely campaigned like Crowley did.

Biaggi promises, in the meantime, to be relentless. “Institutions change when the people inside them change,” she says. “I’ve seen that happen in Albany, and I know it’s possible in Washington.”