This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

One day in 2006, Dorothy Roberts went in for a conference with her youngest son’s teacher. The boy, said the teacher, had too many unexplained absences from his public kindergarten in Evanston, Illinois, most egregiously missing the class’s Thanksgiving activities. “All the other children made Indian headbands out of paper and feathers,” the teacher chided, according to Roberts. “Before I could respond, the teacher gave me a strict warning: ‘If your son continues to miss school, I’m going to call a truancy officer to visit your home.’”

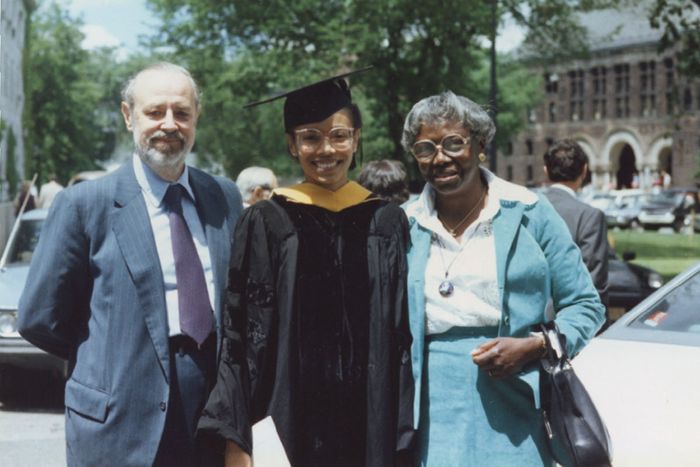

Roberts’s son, her fourth child, had actually been accompanying his mother — a law professor and public intellectual who has helped provide the theoretical and historical backbone of the reproductive-justice movement — to a lecture she was giving in England. Five years earlier, Roberts had published the first of two books arguing that what she calls family policing, more commonly known as the child-welfare system, singles out Black mothers for investigation, sanction, and separation. At their next meeting, Roberts told me, the teacher’s suspicion, even contempt, had disappeared: “She must have looked me up and seen that I was a Northwestern professor.”

Roberts tells this story in a book she published in the spring, Torn Apart: How the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families—and How Abolition Can Build a Safer World; she recognizes that her class and education prevented further inquiry into her son missing school. “I don’t think I deserved any special treatment,” she told me recently. “I see it as the disparaging of Black mothers who don’t have the credentials I have.”

In the country that leads the world in revoking parental rights, the odds of a Black child being forcibly separated from their parents and placed in foster care before turning 18 is more than one in ten, mirroring our racially skewed record on incarceration. “Only 16 percent of children enter foster care because they were physically or sexually abused,” Roberts writes in Torn Apart. What the system calls neglect most often stems from poverty: “living in dilapidated or overcrowded housing, missing school, wearing dirty clothes, going hungry, or being left at home alone,” she writes. Roberts’s sincere provocation is to call for that system to be thrown out entirely.

The post-Roe era has made Roberts’s work grimly essential as both prophecy and cautionary tale. In these early days, directing outrage to the obvious horrors has been easy: the bleeding women with wanted pregnancies who aren’t dying fast enough to meet an infinitesimal legal exception; the inarguably victimized pregnant child with ever fewer places to turn for an abortion. These are catastrophes only the most monstrous excuse, and they make for uncomplicated pro-choice talking points. “I call it poster-child feminism,” says Loretta Ross, the organizer and foremother of reproductive justice.

By contrast, Roberts’s work, in Torn Apart and in her canonical 1997 book, Killing the Black Body, staked the theories of reproductive justice on the experiences of people whom mainstream institutions and figures, including liberals, long ago abandoned — drug users accused of birthing “crack babies”; welfare recipients targeted for forcible sterilization; teenagers given long-term contraception without their clear consent. Roberts’s work demands us to extend imaginative and political sympathies to the reproductive autonomy of some of the most disdained members of society, who are overwhelmingly Black and poor women, in part because they are the ones who will bear the heaviest burden of criminalization. Indeed, they already have.

When I went to see Roberts at the University of Pennsylvania, where she now teaches law, sociology, and Africana studies, less than two weeks after Roe’s demise, she told me that early in her career she often had to explain to her colleagues what these drug users had to do with reproductive freedom or constitutional rights. Roberts responded that they were being punished not for using drugs but for their decision to stay pregnant, enacting fetal personhood via the war on drugs. That was with a floor set by Roe, which sometimes provided a defense in these prosecutions; without it, “child endangerment” can begin at conception. By dint of geography, poverty, race, or class, or all of the above, today’s patient denied an abortion, or prosecuted for having one outside the law, is likely to be tomorrow’s target for a child-welfare investigation.

In person, Roberts is wiry and energetic, and disarmingly accessible. She describes herself as “very mild-mannered.” On at least three different occasions people who know her, either personally or by reputation, remarked to me how young Roberts is and were surprised to learn she is 66. It’s not unusual for an academic to say they want to inspire movements, but to an extent more sweeping and durable than most, Roberts has accomplished that. Ross credits Roberts with “adding theory to our practice” and assigns excerpts of Killing the Black Body, which she refers to simply as KBB, to her students.

A quarter-century after its publication, organizations like the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund and Medical Students for Choice give it to new hires at headquarters or outright require them to read it. A work of stunning historical and analytical breadth, it traces the state-sanctioned, often violent regulation of Black women’s reproduction, including but far beyond the ability to refuse motherhood. “In contrast to the account of American women’s increasing control over their reproductive decisions, centered on the right to an abortion,” Roberts wrote back then, “this book describes a long experience of dehumanizing attempts to control Black women’s reproductive lives.”

The book’s framing reconciles policies that curb Black and low-income parenthood with ones that force pregnancy and childbirth. “The objective of reproductive control has never been primarily to reduce the numbers of Black children born into the world,” Roberts writes. (She quotes Thomas Jefferson writing to his plantation manager in 1820, “I consider a woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man on the farm.”) Instead, such control “perpetuates the view that racial inequality is caused by Black people themselves and not by an unjust social order,” she argues.

Failing to advocate for the most disfavored, Roberts says now, “weakened the mainstream reproductive-rights movement. It allowed the right to expand the protection of the fetus and criminalize pregnancy more broadly.” The surveillance and policing of Black mothers — whether for drug use, purported neglect, or just having “too many” children — has already provided a ready blueprint for enforcing the current abortion bans, down to the hospitals calling the cops. “We can see how these policies, fueled by vilified stereotypes about Black mothers, are tested on Black mothers first,” she tells me. “And then they expand.”

Growing up in Chicago’s Hyde Park in the 1960s, Roberts had a sense of her father interviewing interracial couples, who became her parents’ friends and whose children became her friends. One parent was her piano teacher; another was the plumber. Her own father was an anthropologist, the inspiration for her desire to be a professor, and a white man who spent much of his life writing a never-published book on interracial marriage. Her mother had been a research assistant on the project, mainly interviewing the women in hundreds of couples.

She’d thought her father’s interest in the subject was sparked by meeting her Jamaican-born mother, at the time one of his students at Roosevelt University in Chicago. Ten years ago, as Roberts packed up her home in Evanston to move to Philadelphia, she came across boxes of files in her basement that had belonged to her late father, which told a slightly different story. Her father’s intellectual passion had actually begun as far back as his time as a 22-year-old master’s student at the University of Chicago, in 1937.

Dorothy was the firstborn, a studious child. “He liked to pull me aside and talk to me about his work,” she recalls. “He would try to convince me that interracial marriage was the answer to America’s race problem. I can remember him as a little girl telling me this. And he also liked to think of me and my sisters as — I hate to say this, because it sounds terrible — but as proof.” She was idealistic even as an elementary-school student, going to activist meetings and passing out pamphlets for Eugene McCarthy’s campaign. “I can remember being proud of walking down the street with my parents,” she says. She believed then that her very existence, flanked by white father and Black mother, sent a message: “‘Look, we could all get along,’ you know? But that was when I was little.”

Her father clearly agreed. In the boxes Roberts found a file on herself, indexed with a dedicated number and containing some of her student papers. “I can recall my mother saying sarcastically, ‘Don’t you know, we’re part of his research,’” she said. She’s been thinking a lot about her mother lately, how rare it was that a Black woman at mid-century would pursue a doctorate, but also how her mother’s ambitions transferred to her children after leaving the program to care for them, and to her husband, whom she pushed to write the book. Roberts recently remembered that along with the nicknames her mother had for her — Firstie, Gift from God, Ray of Sunshine — she would also say, “You’re my Ph.D.”

Her father died in 2002 never having finished the manuscript. (Simon & Schuster demanded back its advance, in the low thousands.) Roberts, now on sabbatical, has decided to write her own book, a memoir that draws on his research but also critiques his premise. By the time she got to college, at Yale, Roberts didn’t even want people to know her father’s race. “I had this idea that if people knew my father was white, somehow that would diminish my identity as a Black woman,” she tells me. Many years later, writing her 2011 book Fatal Invention, which took on genetic myths of race, finally helped her fully reconcile it. “I realized that your ancestry doesn’t determine your identity,” she says. Still, she hasn’t wavered in her skepticism of her father’s Utopian vision: “I’ve been much more convinced that there has to be radical change in America before there can be any possibility of interracial intimacy that could be seen as contesting white supremacy.”

At Harvard Law School, while taking antitrust with Stephen Breyer, Roberts started noticing a tall, well-built man around campus. He was a doctoral candidate in education 13 years her senior. Coltrane Chimurenga, the name he had chosen for himself, had taught at the College of Struggle in California and could expound on politics for hours. At the time, there were only two Black professors at Harvard Law, including Derrick Bell, a progenitor of critical race theory. Chimurenga had brought to Cambridge his prodigious library of Frantz Fanon and W.E.B. DuBois and Mao’s Little Red Book, books Roberts read as they grew closer. Chim, as she called him, would come to refer to Roberts as Shona, and after the two married, they named their first son after the anti-colonial author Amílcar Cabral.

After graduation, Roberts clerked for civil-rights icon Constance Baker Motley, the first Black woman to serve as a federal judge. Roberts had hoped for stirring civil-rights cases, but the southern district of New York’s docket was heavy with business and finance. One case involving minors who wanted to marry against their guardians’ wishes, including a pregnant teen, came close to her imaginings. Roberts drafted an opinion proclaiming a right to marry under the 14th Amendment. Judge Motley pragmatically told her such an argument would be instantly overruled by the appeals court, and decided the opposite way. “She felt a lot of pressure to be seen as a legitimate judge who understood and followed the law,” Roberts says now. “Because she was viewed as radical by the right wing.” Motley was right about the appeals court, which affirmed her decision.

Motley’s compromises didn’t appeal to Roberts — “I’ve always wanted to be unconstrained in my vision and my advocacy” — but her next gig was as a litigation associate at the white-shoe law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. (Chimurenga, she says, “knew it paid the bills.”) In 1982, pregnant with Amilcar, she was told at the firm that no one had ever heard of an associate being pregnant, but managed to cobble together some decent maternity leave anyway. Over those six years, she gave birth to three children at home: in a rented brownstone on South Oxford Street in Fort Greene; in an apartment in Jackson Heights; in a house she bought in Hempstead, on Long Island, respectively. Today, she isn’t sure if she already knew what would become a core part of her research, that hospitals themselves could be a deadly threat to pregnant Black women, or if it was just that Chimurenga had introduced her to the home-birth midwives, who were “Puerto Rican, very political, revolutionary.”

One evening in October 1984, Roberts was at home with her 2-year-old and her 3-month-old when the phone rang. The FBI and the NYPD’s joint counterterrorism task force, she was told, was waiting at her door. Placing the toddler in the crib and hoisting the baby on her hip, she opened the door to what felt like dozens of armed officers, who began to interrogate her and ransack the apartment. Chimurenga, accused of being a terrorist ringleader of what came to be called the New York 8, was arrested later that night. They later learned that for nine months, a surveillance operation engaging up to 100 agents a day had been tracking him and his fellow activists. All this came as a shock to Roberts, she says now: “I knew he was involved in political activism. I knew he opposed the NYPD. He had stood up to them. I knew that they didn’t like him.”

For months, Chimurenga remained in Metropolitan Correctional Center, one of the first people to be so detained under a provision of a new terrorism law. The prosecutor, a 40-year-old hotshot named Rudolph Giuliani, charged the eight, largely under racketeering statutes, of conspiring to use murder, kidnapping, and arson to rob an armored truck and free two prisoners who had famously been convicted of robbing a Brink’s truck. He faced a possible 20-year sentence.

Roberts’s parents showed up to help, and Paul, Weiss stuck by her, even offering a pro bono criminal attorney. She needed one: Like several other spouses of the charged, she refused a subpoena to testify before the grand jury. Unlike the others, though, she managed to escape detention. Her fancy lawyer helped, as did the surveillance records showing she essentially did nothing but work at the firm, take care of their kids, and go to church. (At 19, Roberts had become a deeply religious Christian, and she still reads the Bible and prays daily.) The contrasts between the charges against Chimurenga, his Harvard pedigree, and his corporate-lawyer wife weren’t lost on the press. He was photographed and interviewed at MCC by this magazine and appeared on the front page of The Village Voice.

Her attorney told Roberts to keep a low profile, but she decided to speak at a rally and allow her and her kids’ faces to appear on fliers in support of the New York 8. She believed they were being targeted for their political activism for Black liberation. “We didn’t always see eye to eye, we didn’t work within the same political movements,” she says of her former husband, “but we supported each other’s work.”

Giuliani was unable to make the most serious charges stick, and in 1985 the New York 8 were convicted only of illegal weapons possession or false-identification charges and sentenced to community service and probation. Chimurenga remained active in left-wing politics; according to his obituary in the Amsterdam News, he approached a police officer who came to his organization’s headquarters and “was pointing his AR-15 at him, ordered him to ‘put that f’ing gun down,’ grabbed the barrel and forced the weapon down.” (Roberts and Chimurenga divorced a few years before he died of cancer, in 2019, and she has since remarried.)

Roberts seldom talks about all this; some of it, she tells me, she had never discussed with anyone. A few years ago, at a conference at Harvard, she was asked how she became a prison abolitionist. “It occurred to me at that point that part of it was having a husband in jail and having police invade my home,” she says. The months they spent apart, the prospect of the days turning into decades, of raising small children alone, were their own form of family separation. Oddly, she says, “I haven’t really thought about that personal experience as much as I’ve thought about other people’s personal experiences.”

In 1987, Roberts read about the Angela Carder case. A working-class white woman in Maryland, Carder had struggled with cancer for most of her life. At 27 years old and 26 weeks pregnant, she lay intubated and sedated at George Washington University Medical Center, which went to court on behalf of Carder’s fetus. They wanted emergency permission to perform a Cesarean that Carder’s parents said their daughter wouldn’t have wanted; later, Carder, drifting in and out of consciousness, gave conflicting answers about her desires. Judge Emmet Sullivan ordered the surgery: “The court is of the view that the fetus should be given the opportunity to live.” The baby lived less than two hours; Carder died after two days.

To Roberts, still at the firm, it was a turning point. “When I read that, I thought, My goodness, if you’re pregnant, they can kill you,’” Roberts tells me. “I swear, I said, “I have to work on this.” Carder, Roberts understood, had lost the rights to her own body simply by being pregnant. “I also had the sense,” Roberts adds, “that if they would do that to her, what would they do to a Black woman?”

She soon found a job teaching at Rutgers Law in Newark, and the family moved to Montclair, New Jersey. By then, panic over so-called crack babies being born to addicted mothers was suffusing newspaper headlines and lurid television shows, along with a thirst for prosecuting women who used drugs during pregnancy. “I immediately thought, I bet these are Black women who are being punished,” Roberts says. She called the ACLU, whose then–staff attorney, Lynn Paltrow, represented the Carder family against GW. The case, Paltrow said at the time, sent a message to “women that the state can control and monitor every aspect of their lives, like prenatal police patrols.” (Paltrow went on to found the National Advocates for Pregnant Women, which has been at the forefront of defending criminalized pregnant people.) The ACLU was also tracking all the cases of pregnant women being prosecuted for drug use, though not their races. Roberts called all the defense lawyers and learned that almost 80 percent of the defendants were Black.

The frame, Roberts thought, had to be pushed even further. “I wanted to write about how racism turned this public-health issue into a crime,” she recalls, “and also the significance of that for how we think about reproductive freedom, that it’s not just a question of gender and sexism and misogyny.” Some senior faculty members warned her that it wasn’t the kind of topic that would establish her in legal academia, and that she was better off waiting until she had tenure, but she ignored them. In 1991, the Harvard Law Review published “Punishing Drug Addicts Who Have Babies: Women of Color, Equality, and the Right of Privacy.” Her conversations with Paltrow had helped Roberts distill her own thinking that the crime these women were being targeted for was not using drugs, but being, and staying, pregnant. “I sometimes felt like we were the only two people in America who understood that punishing people for being pregnant was just as important as punishing people for having abortions, that they were connected,” Roberts says. “Any conduct or omission that could be seen as risky to a fetus, or a potential fetus, can be criminalized.”

At Paul, Weiss, she’d gotten used to writing on long yellow legal pads, and she remembers pulling over her car on the side of the road around that time to begin writing down the connections that rushed into her brain. The prosecutions, yes, but also welfare reform; sterilization abuse; Norplant, a new-birth control method then being touted as a solution to poverty without much consideration of side effects or informed consent. Slavery. That foment became Killing the Black Body, which instantly electrified not only organizers in the field but also a generation of legal thinkers. “Dorothy is like a Harriet Tubman of law,” says her friend and fellow law professor Michele Goodwin. “She opened the gates for so many others, including myself.”

Roberts managed to prove her senior colleagues wrong by getting those invitations to visit, and then teach, at prestigious law schools after all. (She had gotten in the habit of taking her kids along everywhere, including conferences — one in the carrier, one in the stroller, and so on.) Even with the gates creaking open, the reception could be begrudging. At Stanford, where she was a visiting professor early in her career, in 1998, a (white, male) student had read a newspaper throughout her family-law class. Only a dozen years earlier, Stanford Law students had begun skipping a required constitutional-law class taught by another visitor, Derrick Bell, and ended up creating a public lecture series taught by other faculty members to replace it. At that point, Stanford had only ever had two Black tenured members, and the administration later apologized for going along with the lecture series. Roberts has a policy against cold-calling — the Paper Chase–style surprise Socratic method still popular with many law professors — instead pre-assigning students to answer questions on specific days. The newspaper-reading student was unprepared anyway, and Roberts said something lightly mocking in response. The class laughed. Afterwards, the student indignantly told her she had humiliated him and that he would tell his father to no longer donate to Stanford. At Northwestern, where she taught for 14 years and held a named chair, a (white, male) student had once raised his hand during her criminal-law lecture and declared that what she said had been refuted by Wikipedia. In fact, Roberts says, he had misunderstood Wikipedia.

While teaching at Northwestern, Roberts remembers, she spoke at a Planned Parenthood event in Washington, D.C., and criticized the notion that birth control was a way out of poverty. Hands went up, “saying that I was unfairly judging Margaret Sanger. And I remember an elderly white woman coming up to me and trying to justify the thinking of even eugenic policies.” She is still seeing versions of that neo-Malthusianism around the Dobbs decision. “It’s true that Dobbs is going to intensify poverty,” she said. “It’s going to intensify maternal mortality and infant mortality. But that’s different from saying abortion is the solution to childhood poverty, or birth control is the answer to teenagers dropping out of high school because the problem is structural racism. The problem is structural income inequality. The problem is racial capitalism.”

Among the arguments of reproductive-justice activists is the inadequacy of the doctrine of privacy, and the related, market-oriented language of choice, however poll-tested to appeal to white moderates. It lives on, including in the speech by Joe Biden the day Roe was shredded. Whether or not a better argument could have swayed the dogged ideologues of judicial conservatism, “privacy” alone could not save Roe.

“It’s so obvious that focusing on the ability to make private choices was a losing strategy. It was just thrown out, dismissed by the stroke of a pen, you know?” Roberts had told me in the courtyard. “That doesn’t mean the idea of freedom that underlies it and actually should have been recognized as the essence of the 14th Amendment isn’t important. We should support a human right to autonomy over our bodies. But we have to have a society where that’s possible.”

For all of her critiques of historically white reproductive-rights organizations, Roberts had no time for the Dobbs concurrence by Clarence Thomas, which had explicitly linked abortion rights with racism. “It’s a false retelling of history because abortion was not an instrument of eugenicists; sterilization was,” Roberts explains. “And abortion is a means of reproductive freedom. Whereas coerced sterilization is a means of population control.” But the neglect of allies, she argues, had given Thomas a soft underbelly to attack. “If reproductive justice were at the forefront from the very beginning, there is no way today people would accept Clarence Thomas’s argument,” she says. “It would be blatantly ridiculous.”

There had been time to add a question to the final exam of her reproductive-justice class about Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s comments at the Dobbs oral argument that the opportunity to drop a newborn at a so-called Safe Havens might offset the harms of banning abortion. Roberts was furious at Barrett’s, and later Alito’s, hand-waving over the violation of forced pregnancy and birth, but she also saw the connections to Torn Apart. If the presumed anonymity of safe havens was breached, as it has been, “you could be subject to a child-protection investigation. Let’s say you have other children, and you drop this child off, and that’s considered child neglect,” she said. “Even if there is some protection against prosecution for dropping the baby off. That doesn’t mean that it couldn’t trigger a child-welfare investigation, unless that’s explicitly written into the law.”

After Shattered Bonds came out, Roberts agreed to try to be part of the solution, this time on the government’s side. She accepted a spot on a task force as part of a settlement against Washington State’s child-welfare department. For nine years, there were action steps and benchmarks and “dozens of meetings with administrators and attorneys at a hotel across from the SeaTac airport,” Roberts writes in Torn Apart. There were anti-racist trainings for caseworkers and lawyers and judges and administrators. “But we were unable to fix the long list of deficiencies that harmed children placed in the state’s custody.” For the 20th anniversary of Shattered Bonds, she initially considered writing a new foreword, then decided she needed to start over with a bolder call: “We must abandon the fool’s errand of tinkering with a system designed to tear families apart.”

The racial-justice protests that crescendoed in 2020, with their calls to defund the police, enthralled Roberts, but they also worried her, because one of the proposed alternatives to policing was to transfer resources to the same agencies she wanted to dismantle. What resonated more showed up late that year, as a small group of New York City activists began blanketing the streets with posters and billboards. One read, “Some Cops Are Called Caseworkers.”

Roberts points out that family-services caseworkers are able to flout due process in a way police aren’t supposed to — for example, searching a home without a warrant — and sometimes the cops come along for their turn in the name of child protection. To people accustomed to thinking of child-welfare investigations as being about protecting kids from violent homes, Roberts has this rejoinder: The majority of substantiated complaints are not of abuse but of neglect. “Rather than operating as a defense against a neglect charge,” she writes in Torn Apart, “poverty works as an enhancement of parental culpability.”

Roberts argues that the system is swamped with neglect complaints that actually stretch caseworkers too thin to find children in actual danger. Meanwhile, women in domestic-violence situations fear asking for help lest they be blamed for putting their kids in a violent situation and separated from them. She tells the story of New Yorker Angeline Montauban, who worked up the courage to call the Safe Horizons hotline about her partner’s violence toward her; the revelation that they had a 2-year-old soon led to an ACS caseworker knocking at their door, despite no evidence he had harmed his son. Because Montauban filed for an order of protection against her partner but wanted her son to keep seeing his father, Roberts writes, her toddler was placed in a series of foster homes for five years. Foster and group homes, meanwhile, are notoriously sites of abuse themselves.

The group behind those billboards had another slogan that stayed with Roberts: “They Separate Children at the Border of Harlem Too.” “I did 1,000 for each borough,” Joyce McMillan, founder of the nascent advocacy group JMAC for Families, tells me. (Almost. “I didn’t do Staten Island because no one has time to go to Staten Island.”) McMillan can recite by heart the names of New York politicians who showed up to rally against the Trump administration’s separation of families at the border. For years, she had been trying to get their ears on behalf of parents impacted by New York’s Administration for Children’s Services, or ACS. “There was no outrage for the children that were removed from their own community domestically,” she says. “You can’t even get their legislative directors.”

A few years ago, McMillan asked Roberts if she would come speak about her work to parents who were fighting the system. “My observation is that she’s always willing to show up,” McMillan says.

This past July, Roberts showed up again for McMillan, this time on Zoom. It was the third permutation of McMillan’s HEAL program, a 12-week workshop to help these mothers — the session I attended was all mothers — process what they had experienced and then train them for activism and talking to the media. JMAC for Families has been lobbying for New York State to pass a package of legislation that includes ending anonymous reporting of child-welfare complaints (though keeping them confidential) and Miranda rights for parents being visited by caseworkers.

The instructor began with an ice breaker. “If you’re writing a book about your life, what would you call it? And what would you want readers to take away from it?” The titles seemed to come easily to the women. I’m A Survivor, chiefly about putting your faith in God. She Moved On, with the lesson being life is difficult but you don’t dwell, and I Won’t Give Up and Reborn and Battling a Broken System. Knockout, its author said, would be about “my life, but I would also write about knowing your rights.” ACS Took My Childhood and Now They’re Taking My Children needed no explanation. McMillan’s was Catapulted, because ACS wanted her to be a victim and instead she became “a monster for change.”

After the instructor led a guided meditation, Roberts began speaking. “People sometimes listen to lawyers in ways they don’t listen to other people,” she explained, “and it helps to have a book.” The history of forced separation of Black families during slavery was a crucial parallel, Roberts told the HEAL participants, but so was what came after the dismantling of reconstruction — a so-called apprenticeship system. “White people would petition to say that Black children were being neglected,” she said, “and family-court judges would declare these children neglected and order them to be apprenticed out to white people, who sometimes are the very same people who had enslaved them prior. Tens of thousands of Black children were put back to work under the authority of former white enslavers in the South.”

In the question-and-answer session, the participants talked about their kids in foster care being put on medications without their consent, about their experiences with domestic violence and the shelter system. They talked about how the government could give families direct support without increasing surveillance, if it was even possible, and the self-perpetuating system of the algorithm designed to identify risks. McMillan pointed out that children in Brooklyn get ticketed for riding bikes on the sidewalk, which kids in the suburbs do all the time, “and they’re not treated as criminals.” She said, “They try to make us think that we are stupid when we point out how ridiculous the system is.”

One of the women offered the send-off: “Thank you for sharing space with us, queen.” Roberts replied, “Thank you. All of you are queens.”

Dismantling the child-welfare system sounds improbable — and politically toxic. But Roberts points out in Torn Apart that it’s already been done. When enforcement in New York City was vastly curtailed by early COVID shutdowns in 2020, it was briefly replaced by a combination of mutual aid and government support, including a series of direct payments. It’s hard to know exactly what happened behind closed doors, but here’s one empirical measure. Law professor Anna Arons crunched the numbers and found that “ACS investigations related to child fatalities—which were required despite the lockdown—dropped by 25 percent between February 2019 and June 2019 and the same period in 2020.”

The night she visited the summit, Roberts had arrived a little late from another meeting, and though she’s writing a memoir, the icebreaker flustered her. “It would have something about gratitude and hope in it,” she managed. “But I can’t come up that quickly with a good title. And what would I want readers to take away from it? I would want readers to take away something about being hopeful despite how distressing the world seems to be, and take away something joyful from it.”

I’d been surprised, when we spoke in Philly, to hear her talk so much about hope. “I haven’t seen such hope and excitement around organizing since I was a little girl in Hyde Park in the 1960s,” she said. “I’m seeing it in uprisings, around the country after George Floyd was murdered, I’m seeing it in this family movement to abolish family policing.” But the backlash has been so fierce, I said: to racial-justice movements, to reproductive freedom in all forms, and it seemed that the people who had once marched felt demoralized and disconnected. “There’s always a backlash,” Roberts replied. “There’s a backlash because you did something powerful that requires a backlash.”

When we talked after the visit to HEAL, I noticed Roberts bristled a little when I referred to her as having done “research” about the lives of these women, going back to meeting with Black mothers in a Chicago basement in 2000 for Shattered Bonds. The term “research” felt to her too clinical, too detached. “Those meetings are part of why I became an abolitionist,” she corrected. “They didn’t just affect me in terms of collecting empirical data. They affected my political aims and desires.”

This wasn’t theoretical for McMillan, either. In 1999, she had been working in the banking industry and had just had a baby when an anonymous tip and a positive drug test wrested away her two young children for two years. McMillan says her drug use was recreational at the time, but that the ordeal eventually pushed her into addiction and homelessness. She lost her house, her car, her job. “They literally destroyed my life,” she says. It took a good public defender and a year of being substance-free to get her children back, and much longer to process the damage done by the separation. McMillan had trouble finding a therapist who didn’t feel like another cop. But in therapy, her younger daughter talked about the vivid memory she had that McMillan had been the one to “steal” her from her real mother — her foster mother.

McMillan remembers how she felt when she first encountered Roberts’s work. It was reading Killing the Black Body, and then Shattered Bonds, around 2015. “It was a truth I didn’t have language for,” she says. “It was a truth that I had lived in the shelter. I saw someone spoke about it. And someone put a name to it. And someone said, I see it too.”