For a brief moment this week, it looked as if Joe Biden’s doom spiral was back. The president had invited allies from across the country to the White House’s South Lawn to celebrate his massive Inflation Reduction Act in a nationally televised ceremony, but a surprisingly torrid inflation report and subsequent stock dive seemed certain to derail the Tuesday festivities and embarrass the West Wing — and to remind everyone of Biden’s unrelentingly grim winter and spring, when the state of the economy had his party girding for a midterm wipeout and even fellow Democrats questioned his place on the top of their ticket.

Yet by midmorning, a different political story had become topic A in the political press. Republican senator Lindsey Graham stole the media spotlight with a freelanced proposal of a 15-week national abortion ban that immediately cleaved GOP leaders and activists and bewildered Democrats. The snarky, negative headlines about Biden never came, and his good vibes rolled on.

Everyone in politics now agrees there’s been a sea change in the run-up to November’s midterms, which are no longer forecast to be a Republican romp at all. Biden’s recent legislative success is partially responsible, and plummeting gas prices surely play a large role, too. The Supreme Court’s repeal of Roe v. Wade, which has activated sustained liberal fury, and Donald Trump’s return as an unavoidable presence, railing against the FBI’s shock Mar-a-Lago raid, are also major factors. Trump has additionally hurt his party’s prospects by backing fringe-right candidates in GOP primaries in states where they’ll have a hard time getting elected.

But there’s a simpler way to put all that: Biden simply isn’t the main character of daily politics anymore — in no small part because the GOP seems unable to stay out of its own way. And his party is reaping the benefits.

It would be easy to go too far down this line of argument. Historical patterns make clear that the president’s party should expect to lose seats no matter how strongly the moment’s political winds are blowing. Democrats are still likely to lose control of the House, and even maintaining a split Senate would be a great result for them. Polling this week underscored how daunting a task this might still be, though: On Wednesday, a Marquette survey showed unpopular right-wing Wisconsin senator Ron Johnson effectively tied with his Democratic challenger, Lieutenant Governor Mandela Barnes, who appeared to be clearly ahead last month.

“What’s important is not to misread this. Democrats aren’t, like, sitting there super-optimistic,” said Biden’s pollster, John Anzalone, trying to reel in expectations — a maneuver that itself reflects how quickly things have changed. But, he said, “we believe we’re in a competitive situation, and that’s a big difference from May 1. We were on the defensive.” He paused to consider the big picture. “No one’s making the prediction that we’re going to kick ass. The prediction is we’re not going to get our ass kicked.”

Overall, it’s a midterm landscape unlike any in recent political history. Veteran Republican pollster Whit Ayres didn’t hesitate when I asked him if he could remember any comparable environment. “No,” he said immediately. “We’ve never had a midterm where a former president was as prominent as this one.”

Trump’s insistence on reasserting himself in the daily political fray — perhaps even as a presidential candidate — has ensured we’re still living in an era of persistently high turnout and maximum engagement. That has upended expectations of low-intensity midterm elections, which developed after last year’s gubernatorial races in New Jersey and Virginia. For much of this year, the prevailing expert assumption was that most races would be grinding battles fought about gas prices and pessimistic views of Biden’s leadership as his approval rating hit new lows and he came to symbolize the stagnancy of Washington, D.C.

The reversal of that conventional wisdom following the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision has been stark. Biden’s initial response was criticized as insufficient by many on the left, but that was soon beside the point from an electoral perspective: A shockingly wide margin of victory for the abortion-rights position in a Kansas referendum demonstrated a wave of new energy from women voters in particular. As the New York Times soon reported, more than seven in ten of the state’s new registrants to vote were women in the week after the court decision, and in the ensuing month a similar pattern held across the country. “In my 28 years of analyzing elections, I had never seen anything like what’s happened in the past two months in American politics: Women are registering to vote in numbers I never witnessed before,” wrote Democratic data analyst Tom Bonier.

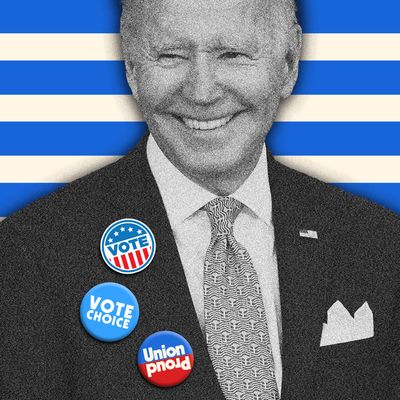

Watching from Washington, Biden is no doubt cheering the shift. His new position is familiar for a man who’s spent a nearly five-decade career in D.C. on the margins of the spotlight but rarely directly in it. Even when he became the Democratic presidential nominee in 2020, his numbers were best when Trump was claiming all the oxygen and Biden could simply stand there as a reasonable alternative.

And now, as the fall races take shape around matters far from his influence, Biden’s approval rating has rebounded unexpectedly. As Anzalone pointed out, Trump had been the only president in modern history whose approval rating had improved between his second summer and fall, but that improvement was marginal. Biden’s has been relatively dramatic: He hit 44 percent in Gallup’s late August survey, a six-point jump from his July low, and Anzalone’s joint Wall Street Journal polling venture with Trump pollster Tony Fabrizio showed a similar improvement from the spring. On Thursday morning, the Associated Press reported a nine-point positive leap.

“The Republicans’ best case is to make this a referendum on the Biden administration and Democratic governance regarding inflation and immigration and crime and a host of other challenges facing the country. Democrats would much prefer this to be a choice election between a Biden future and a Trump future,” Ayres said shortly before a handful of hard-right Trump allies won the final Republican primaries of the year in New Hampshire, apparently improving Democratic prospects in the battleground state just as Trump railed online about an FBI crackdown on his conspiracist buddy Mike Lindell.

Ayres continued, “The former president appears to be cooperating in this endeavor.”