This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

As CEO of the nation’s largest school system, Chancellor David Banks already had an outsize portion of power, influence, and visibility. He recently kicked things up another notch by proposing to his longtime girlfriend, Deputy Mayor Sheena Wright, who is widely expected to be elevated to first deputy mayor by Eric Adams early next year.

Banks laughed when I asked about the betrothal. “It happened about three weeks ago. It only took me ten years,” he said. “We have been talking about this for a while and now living in Harlem together, and I said it’s time. We’ve both done this before, so just taking our time, no rush. We’ve got a great relationship, great partnership. We’ll probably get married in summer. We’re mapping it all out now.”

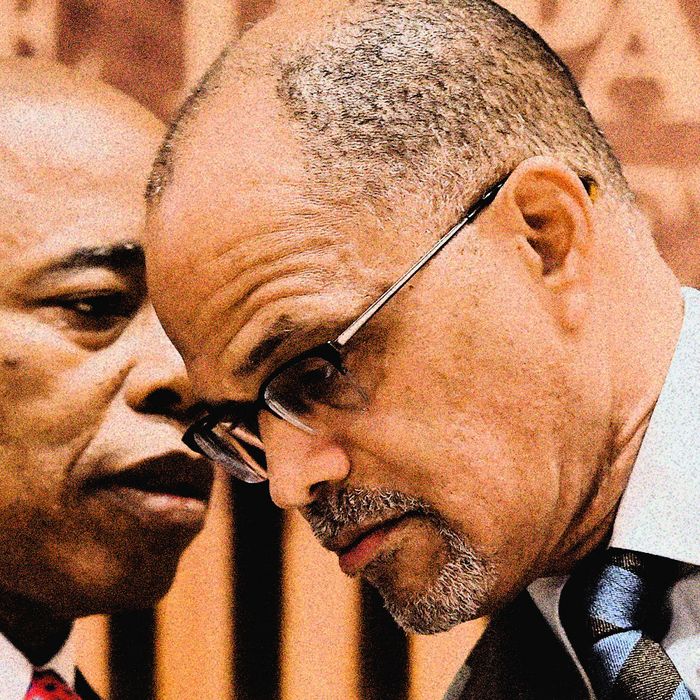

With Banks running schools from Tweed Courthouse, his fiancée soon to be overseeing day-to-day operations next door at City Hall, and his brother, Phil Banks, a few blocks away at 375 Pearl Street quarterbacking anti-crime efforts as deputy mayor for public safety, the wisecrack in political circles is that Eric Adams’s mayoralty should be called the Banks administration.

For Adams to hand over so much power is remarkable in itself. This is a chief executive who frequently reminds the public “I’m the mayor” and typically refers to city employees as “my police officers” or “my teachers.” And despite his reputation for bouncing unpredictably from one event to another, Adams is a creature of habit when it comes to his top staff, relying heavily on a few trusted friends, many of them fellow veterans of the NYPD.

First among equals on political matters is Ingrid Lewis-Martin, whose title of chief adviser to the mayor actually understates her closeness to Adams (“I am his sister ordained by God,” Lewis-Martin has said; her husband, Glenn Martin, entered the NYPD at the same time as Adams and the men were patrol partners). Adams’s chief of staff, attorney Frank Carone, another close adviser, is leaving City Hall at the end of the year and will serve as chair of the mayor’s 2025 reelection campaign.

That leaves much of the rest of the day-to-day operations of administration under the watch of the Banks brothers (whose father, Philip Banks Jr., spent 27 years in the NYPD and was a formidable community leader in his own right, serving as president of 100 Black Men).

Is it the Banks administration?

“I’ve heard that term being used,” David Banks told me. “But listen, we all work very closely together, and we’re all doing the best that we can on behalf of New York. We love New York, just like you do.”

But city government doesn’t run on love. Banks, like his predecessors, has to simultaneously impose order on a sprawling bureaucracy and tangle with formidable entrenched interest groups — including the teachers union, the State Legislature, the City Council, and ever-shifting coalitions of parents and advocates — who all want to shape, share, snatch, or neutralize his power. Nowhere is that more true than on the hot-button issue of how admissions to the city’s most coveted and competitive schools will be handled. Unlike many school districts, New York’s sprawling array of middle and high schools are not simply open to whichever kids happen to live nearby.

Entrance to the most competitive high schools is, by state law, determined by a strict ranking of scores on the SHSAT, a standardized multiple-choice test. The use of the test — which does not include a writing sample or other measures of ability — has long been controversial. Beyond that, other well-regarded middle and high schools don’t require the SHSAT but use screening methods like face-to-face interviews and assessments of a student’s academic records. That screening process, some critics charge (backed by a fair amount of research), creates schools that are exclusive and racially segregated.

The controversy bedeviled the de Blasio administration, which vowed to reduce racial segregation and dropped screening procedures when the COVID pandemic forced schools to close. But in a break with that policy, Banks recently announced that competitive admissions to some middle schools will resume. For high schools that use screening criteria, admissions will favor students who score in the top 15 percent of their class and maintain a minimum 90 average in core subjects.

“I heard across the city from a wide range of folks who have different thoughts and ideas and opinions about this thing,” Banks told me. “These folks have been really upset; they said, ‘My daughter gets a 99, but you mean to tell me somebody with an 82 can get in just as easily as she can? What’s the incentive for her to work hard if everybody’s going to be thrown into just this large lottery pool?’ So I put in an incentive and said I believe in merit. I absolutely do.”

To opponents of screening, Banks has an answer based on his experience launching and running the Eagle Academy schools for inner-city boys. “I’m not coddling kids. I don’t believe in that; I never have,” he says. “Even at Eagle Academy — where we had the group that everybody was shying away from, Black and brown boys — we leaned in and told them the mantra at Eagle is ‘Everything is earned, nothing is given.’ And these kids will rise.”

Banks ruffled feathers recently when he carried that message to an audience of corporate power brokers at a breakfast address to the Association for a Better New York. His exact words: “If you’ve got a child who works really hard on weekends and putting in their time and energy, and they get a 98 average — they should have a better opportunity to get into a high-choice school than, you know, the child you have to throw water on their face to get them to go to school every day.”

The chancellor’s words, complained one advocate, “lacked empathy.”

With or without verbal empathy, Banks has no choice but to placate parents and organizations pushing for screened admissions in the middle and upper grades. City schools have lost 70,000 students over the last two years and 120,000 over the last five, he says — an enrollment decline that will inevitably trigger budget cuts under the crucial per-pupil formulas that determine funding levels.

“The elephant in the room is that New York City public schools are hemorrhaging students,” Mona Davids, co-founder of the New York City Parents Union, told me in August. “Parents are fleeing and taking their children with them to charter, parochial, private schools, and some are even homeschooling their children. So this is what we have to address.”

A number of other challenges have landed on Banks’s desk.

More than 17,000 migrants seeking political asylum have arrived unexpectedly in New York in recent months, suddenly adding about 5,000 new students into a system with a perennial shortage of bilingual teachers and counselors. The chancellor hastily struck a deal to recruit 25 Spanish-speaking instructors from the Dominican Republic immediately, with another 25 to come in the fall. Next month, during the annual Somos el Futuro political conference held in San Juan, Banks says he plans to meet with local officials to help recruit Puerto Rican bilingual teachers to come work in New York.

Violence is also haunting the schools. In September, a 15-year-old student at Brooklyn Laboratory Charter School was shot and killed at a park in downtown Brooklyn shortly after school let out. More recently, a 19-year-old school worker named Ethan Holder was shot and killed shortly after walking out of P.S. 203 in Brooklyn; another teenager has been arrested and charged in that case.

“We’re finding an increase of weapons in schools. They’re not bringing them to fight or hurt people in schools but so that they can ensure their own safety going home from school and coming to school,” says Banks. “Kids in school are getting along well enough. They bring those things because now they’ve got to navigate the buses and the trains and the neighborhood.”

Banks’s response has been to spend $9 million on Project Pivot, which will allow 138 schools in high-violence areas to hire and connect with community-based groups that specialize in tutoring, mentoring, counseling, gang intervention, and other strategies to lower the rates of violence. The DOE will monitor indicators like the number of weapons seized, absenteeism rates, and academic scores to determine which programs are most effective.

While Banks is the visible face of education, the larger politics of convincing anxious parents to keep their kids in the system ultimately lies with the mayor.

“I think that Eric Adams has made a huge mistake politically because he has really alienated a huge number of parents across the system who no longer trust that he has the benefit of their kids at heart, that he is not really looking out for their kids,” says Leonie Haimson, the executive director of Class Size Matters, an advocacy organization. “The fact that Adams goes around the city consistently and claims there are no budget cuts to schools is absolutely absurd and ridiculous and makes people trust him less because they know very well that there are big budget cuts to schools.”

Reductions in many school budgets have indeed been announced, in keeping with the normal mid-semester practice of adjusting money and personnel depending on student-enrollment levels. In a shrinking system, some schools inevitably take a hit.

Within that maelstrom of daily bureaucratic and political combat, Banks wants to reorient the system to make sure kids learn to read, write, and calculate in the early grades and exit high school ready for college or a career.

“In 2009, we had 80,000 kids in the ninth grade. Ten years later, only 18,000 of those 80,000 actually got a college degree,” Banks told me. “We have such a focus on standardized exams — but you’ve got kids who can pass standardized exams but have no idea what the attorney general does. They don’t know how the City Council works. They don’t know anything about personal finance. So what are we doing? And the worst part of it is that for all those other kids, we haven’t even given them the skills, the credentials to get a job. We haven’t prepared them for anything.”

Banks’s attack on the problem mostly involves low-visibility, unsexy strategies like implementing a universal screening for dyslexia and shifting to a phonics-based curriculum for young readers. He also has an urgent need to make the DOE better — much better — at executing basic tasks like paying vendors on time. A recent New York Times story cites hundreds of early childhood programs whose contracts with the DOE have been paid late or not at all: A research organization found that, as of the end of the fiscal year in July, “679 outfits were owed more than $460 million. Among them, 19 organizations were showing deficits of $5 million or more.” One organization, Sheltering Arms, recently announced it will soon permanently close a program serving 400 kids because of $2 million in unpaid reimbursements from the city.

Banks has begun remaking the DOE bureaucracy, replacing 15 of the system’s 45 superintendents. “I think they’re off to a good start in the sense that they have conviction about what’s important. It’s very important to be the captain of conviction in a space that’s highly political, where there are so many interest groups and you can get turned around,” says Eva Moskowitz, the CEO of the Success Charter Schools. “Unfortunately, politically, you only get to do two or three things in a four-year cycle. And I think they need to speed it up so that the New York City public knows exactly what their two to three priorities are.”

So what does Banks consider his top priority?

“The biggest job that I have as chancellor is to help kids to see the power of possibility,” he told me, vowing to ramp up the number of internships and part-time jobs for students. The plan includes a newly built podcast studio at Tweed that will be used to interview guests from a wide range of jobs.

“If kids think they could be in a profession, they’re not running with gangs and shooting people because they see ultimately where school can lead them,” he said. “Kids who engage in that kind of behavior live from day to day. They have no idea about the possibilities for their lives. So you live from moment to moment; it’s like living in the darkness — and kids who live in darkness do crazy, stupid things. My job is to shine the light.”

The reality of city politics dictates that no commissioner, however talented, can outshine the mayor. The last guy who tried that was former NYPD commissioner William Bratton, who famously appeared on the cover of Time magazine as the architect of a successful attack on crime in New York — which enraged his boss, Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who wasted no time pushing Bratton out of the job.

The Banks brothers — whose father navigated the often cutthroat politics of One Police Plaza — know how the system works. Phil Banks rarely makes public statements and doesn’t disclose where he meets with NYPD commissioner Keechant Sewell. David Banks frequently notes in private that political matters — like demanding federal aid for the migrant crisis — ultimately get decided at City Hall.

They, and future First Deputy Sheena Wright, recognize that this is their time to shine — as long as everyone remembers who the star of the show is.

Such are the politics of the new Adams-Banks administration.

More From One Great Story

- They Missed Their Cruise Ship. That Was Only The Beginning.

- What Is MAHA?

- The Press Is Down and Shut Out in Palm Beach

- Finding Jordan Neely