It’s a pure toss-up in a perennial battleground, perhaps the likeliest race in the country to determine the future of the Senate in next week’s midterms. But you might not know it outside Nevada.

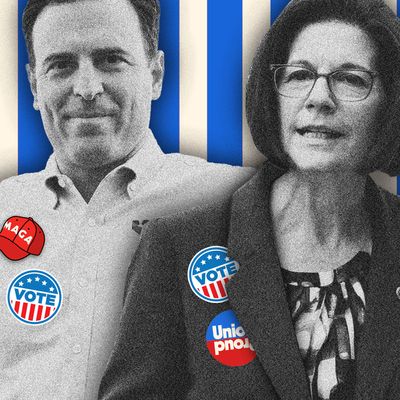

Pollsters have surveyed the race this fall less than any other top-tier contest, like the ones in Georgia, Pennsylvania, or Arizona. Neither the Democratic incumbent nor her Republican challenger has been the focus of splashy features, and both have significantly lower national profiles than their counterparts in other states. By the end of October, Google News revealed about half as many stories mentioning Catherine Cortez Masto as Georgia’s Raphael Warnock and one-tenth of Pennsylvania’s John Fetterman; the ratios comparing Adam Laxalt to Ohio’s JD Vance or Georgia’s Herschel Walker weren’t much better.

It’s not that the Nevadans aren’t objectively interesting, central to national trends, or poised to make history in Washington. They’re all three.

Laxalt, an anti-illegal-immigration crusader and the former co-chairman of Donald Trump’s last campaign in Nevada, is a 2020 election denier who spoke at a “Stop the Steal rally,” argues for a 13-week ban on abortion, and has even seen some of his own family members endorse his opponent. Local Democrats, who have fought him for years as he served as state attorney general and ran unsuccessfully for governor, can hardly believe he’s avoided being seen in the same extremist camp nationally as fellow right-wing candidates like Arizona’s Blake Masters or New Hampshire’s Don Bolduc. He’s not quite a celebrity like Walker or JD Vance or Pennsylvania’s Mehmet Oz, but Laxalt has leveraged his high name recognition in the state (his grandfather, Paul Laxalt, was a senator and governor) and a closing-stretch focus on inflation to position himself as a mainstream option despite his open-armed embrace of the ex-president and his talk of a “rigged election.” (Laxalt even pushed local officials to audit the vote long after the election was over.)

Cortez Masto, meanwhile, is the first and only Latina senator, the daughter of an influential Las Vegas pol, and a product of the Harry Reid political machine; the former Democratic leader handpicked her, also an ex-state AG, to replace him in the Senate when he retired in 2016. Even her opponents concede that she has yet to take a wrong step in her by-the-books reelection campaign. But absent a signature issue or achievement or even much of a defined reputation in Washington, D.C., she’s been tasked with navigating the unpopular Biden administration’s economic record in a state that’s still recovering from a pandemic that blasted its hospitality industry and where the GOP is working hard to make inroads with the large Hispanic population.

The contest, which is universally acknowledged as a dead heat, now appears better positioned than any other to tip control of the Senate, potentially determining not just the direction of Biden’s presidency but also setting the stage for the 2024 election. Alongside a similarly hard-fought governor’s race, it’s one reason why Las Vegas has been inundated with TV ad money — more than any other media market in the country, according to ad trackers. It’s why Democratic Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer made sure to update Biden on the race on the tarmac outside Air Force One in New York last week. (He was caught on a hot mic being optimistic: “Picking up steam.”) And it’s why Biden himself ended a fundraiser for Nevada’s House delegation the night before with a last-second unrelated plea to the donors: “And by the way, while you’re doing this, reelect your senator. She’s first-rate. Thanks.”

It all adds up to a frenetic finish for a tense race in which the candidates couldn’t even agree to debate and where both believe the result is now simply a matter of turnout — they are scouring the state to persuade every last eligible Nevadan to cast a ballot.

On the afternoon of the last Tuesday in October, Cortez Masto took time after voting early in East Las Vegas to greet supporters at a Mexican seafood restaurant down the street. She knew that just about 15 miles to her south, Laxalt was appearing with Donald Trump Jr. Cortez Masto was introduced by two first-time voters, who spoke in English and Spanish, before immigration attorney turned assemblyman Edgar Flores took the microphone and pointed out that Laxalt opposed a pathway to citizenship for migrants who crossed the border illegally.

Cortez Masto eyed the packed tables piled with ceviche and fajitas and shared a short, simple message before going from table to table to hammer it home: “I can’t stress enough what I learned from my parents and my grandparents,” she said. “Our votes matter!” She lingered in particular at a table by the window full of volunteers in the telltale red shirts of the powerful local Culinary Workers Union.

The union, a major component of Democrats’ turnout engine, was the only left-leaning group in the state to knock on doors in the midst of the 2020 pandemic. Biden beat Trump by two points in the state, and now the group has expanded its sights, aiming to break last cycle’s mark and hit 1 million households, including half the Latino and Black voters in the state and over a third of the Asian American ones. Cortez Masto needs every last door knock at the tail end of a difficult stretch for the local party. After the state Democratic organization was taken over by a group of democratic socialists, its central staff and infrastructure — widely associated with Reid — bolted to a parallel group, all of which complicated the effort of unifying Democratic tactics. And when Reid passed away last year, his famed local political machine lost its director, leading to serious questions on the ground among liberals unsure if the state’s many influential labor groups could stay on the same page.

That trouble has come at a rough time for Cortez Masto, who won by just two points in 2016. Though Democrats currently control both Senate seats, the governor’s mansion, and the state legislature, local officials uniformly dismiss the notion that Nevada is anything short of a full-fledged swing state, especially in a national environment that’s hostile to their party. “Nevada’s not blue. It’s not light blue. It’s a purple state, and we’ve won the last several cycles,” said Ted Pappageorge, the Culinary Union’s secretary-treasurer.

Add to that basic fact the grim dynamics of the last two years and Cortez Masto’s challenge comes into focus. For one thing, the hospitality industry has seen immense upheaval since the onset of COVID, and the state’s huge population turnover limits her power of incumbency, as not all the Democratic-leaning voters have pulled the lever for her before. And while the state is heavily Latino, that’s a population among whom Republicans — at least in some places — have been gaining ground. Nevada is also relatively poorly educated compared to other states, a friendly fact for a GOP that has strengthened its hold among non-college-educated Americans.

That Laxalt has managed to maintain a tie in public polling is also discouraging to Cortez Masto allies, who believed he would struggle among some Nevada Republicans because of his hard-right views. The state had a GOP governor and senator until 2019, but moderate Governor Brian Sandoval was far from Trump-aligned and Senator Dean Heller was publicly tortured in his support for the then-president. Sandoval even refused to endorse Laxalt’s bid to replace him. But Nevada has seen prices rise especially drastically, and Laxalt’s focus on inflation has apparently helped him consolidate doubters.

Cortez Masto has not shied from the economic discussion, but she has found that there is no one surefire way of distilling the national Democratic posture into a simple message. In this, she is far from alone. In a trio of focus groups I was able to watch last week, even Biden-friendly voters had difficulty spelling out many details of his Inflation Reduction Act. (The groups, conducted for the Democrat-aligned group Navigator, featured strong Democrats in Pennsylvania, weak Democrats in North Carolina, and Arizona independents and Democrat-leaning independents.) Party operatives have thus taken to giving candidates and groups specific guidance: “We’ve found that when talking about the IRA, the things to really uplift and highlight is the health-care provisions of the law,” said Navigator pollster Bryan Bennett, pointing specifically to lowered premiums, the imposition of a cap on insulin prices for seniors, and lowering prescription prices through Medicare negotiation.

This focus makes intuitive sense, but the Culinary’s door-knockers have found that just as voters seldom bring up Trump with their canvassers, they only rarely bring up Biden or his agenda, either. The union’s solution has been to focus its messaging on what it calls its “Neighborhood Stability” agenda, zeroing in on rent prices and policies while urging voters to back the Democratic ticket. The argument, which supports the prohibition of rent increases during the first year of tenancy and proposes a 90-day notice on future increases, centers on corporate and Wall Street takeovers of local housing. “All you gotta do is spend five minutes talking to voters at the doors and people understand: You have to talk about kitchen table issues and a plan to fight back,” explained Pappageorge. “What’s good is no one thinks the Republicans have any credibility on these issues.” It’s separate from Cortez Masto’s pitch, but she’s relying on the union’s support and has done nothing to detract from it.

Nonetheless, she has latched more on to messaging about GOP ties to big corporations. She has run ads highlighting Laxalt’s relationship with “big oil” as a way of trying to make him seem culpable for gas prices. The evidence: As attorney general, he sided with ExxonMobil as it faced an inquiry into its downplaying of climate change.

Yet even as many Democratic candidates have been counseled to stay away from the matter of election denialism and January 6 so as not to make it seem like a partisan matter that they’re using to try to win a popularity contest, she has also run ads repeatedly pointing out Laxalt’s connections to Trump and his position on the 2020 race. But it’s an inescapable issue even if voters aren’t bringing it up: Jim Marchant, the Republican nominee for secretary of State, has vowed to make Trump president again even as he runs for the office that oversees elections. Meanwhile, the state election staff has been decimated by a lack of trust and support, and election supervisors have quit or announced plans to depart in ten counties.

Still, it’s not Cortez Masto’s main argument. Strategists have noticed the issue falling off in importance with voters. In earlier focus groups, people “saw election deniers as a serious thing, but now it’s just being seen as just another political lie,” said one senior Democratic operative. In the Arizona group I witnessed, one participant rolled her eyes and argued it was time to move on from the election-denial issue since January 6 was nearly two whole years ago. Instead, Cortez Masto has spent significant money highlighting Laxalt’s position on abortion. That issue still seems to be an energizer: Navigator has found that Democratic and Republican motivation to vote is still even, as it has been since the Dobbs decision. Before that, the GOP had a double-digit edge.

But the focus shifts depending on her audience. In East Las Vegas, the idea was plainly to reassure Latino voters that Democrats still had their back. Polls have shown Cortez Masto far ahead among this population but that they are behind other groups in their motivation to vote. Laxalt, seeing a chance to cut her margin, has been running a closing-stretch ad in Spanish (which neither of them speaks fluently) tying Cortez Masto to Biden and inflation. The Democrat, meanwhile, has sought to remind voters that as attorney general Laxalt sued the Obama administration to block DACA — the “Dreamer” program designed to benefit childhood immigrants to the U.S. In person, Cortez Masto’s introducers reminded the diners multiple times that she was, herself, the Senate’s only Latina, and the decorations made the point hard to miss. The walls were dotted with her campaign signs proclaiming, “¡UNA DE LAS NUESTRAS!” One of our own. The idea was to ensure everyone there, and all of their friends and families, got their ballot in as soon as possible.

The pitch felt Nevada-specific. The dynamic is national. “My expectation,” said Bennett, the pollster, “is that the turnout will be the highest it’s ever been in any midterm election.”