Part of what was so surprising about the 2022 midterm-election results is that they defied the historic pattern of major House midterm losses for the party controlling the White House — particularly when the president in question had job-approval ratings as chronically low as President Biden’s. So one of the major questions going forward is whether this relative Democratic overperformance indicates that the party and its putative 2024 nominee Joe Biden should be rated an early favorite as we enter the presidential-election cycle.

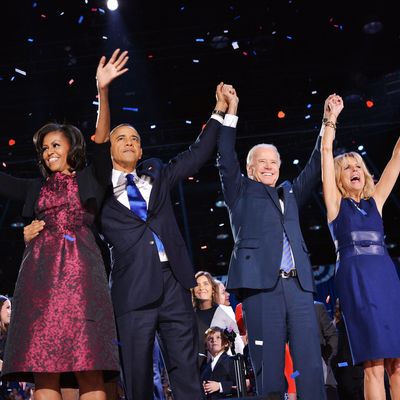

In much of modern political history, there has been a metronomic relationship between midterms and presidential elections, particularly with respect to presidential-reelection cycles. The last two Democratic presidents suffered really bad midterm outcomes before bouncing back to win reelection by relatively decisive margins. Certainly Biden himself is acutely aware that after losing the House national popular vote by 6.8 percent in 2010, the Obama-Biden Democratic presidential ticket won the popular vote in 2012 against Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan by 3.9 percent (comparisons of midterm House vote percentages and subsequent presidential percentages have a bit of an apples-to-oranges character, but it’s the best data we have for electoral swings). And as a Washington veteran, Biden would also be aware that in 1996 Bill Clinton won reelection by an 8.5 percent margin (with his percentage of the total vote depressed by the third-party candidacy of Ross Perot) after Democrats lost the 1994 House national popular vote by 6.8 percent.

The size of midterm-to-reelection swings for Democrats recently may have been influenced by the so-called “midterm falloff” phenomenon wherein certain Democratic-leaning voting groups (e.g., Black, Latino, and under-30 voters) tend to underparticipate in non-presidential elections. There was actually significant evidence of a midterm falloff in 2022, which means Democrats really did overperform among persuadable voters. But even Republican presidents have usually made some metronomic gains. In 2018, Republicans lost the national House popular vote by 8.6 percent. In 2020, Donald Trump lost his reelection bid by a significantly smaller 4.5 percent. But it hasn’t always worked out that way. In 2002, in a bigger shocker than 2022, Republicans won the House national popular vote by 4.8 percent. Two years later, George W. Bush won reelection, but by a smaller 2.4 percent margin. Anything like that kind of trend would be very bad news for Democrats in 2024 since (a) they did, after all, lose the House national popular vote by 3 percent in 2022, and (b) Biden needed every bit of that 4.5 percent advantage to beat Trump in 2020.

Trump’s near upset in 2020 provides a reminder that it’s the Electoral College that determines presidents, not the national popular vote. After 2016, it became common to assume that the Electoral College massively tilted presidential elections toward Republicans generally since Trump won while losing the popular vote by 2.1 percent (just as George W. Bush did in 2000 while losing the popular vote by 0.5 percent). Actually, the impact of the Electoral College may vary cycle to cycle (it almost certainly helped Obama and Biden in 2012). And a look at the state-by-state results for the two parties in 2022 indicates that heading toward 2024, Democrats might again have an advantage.

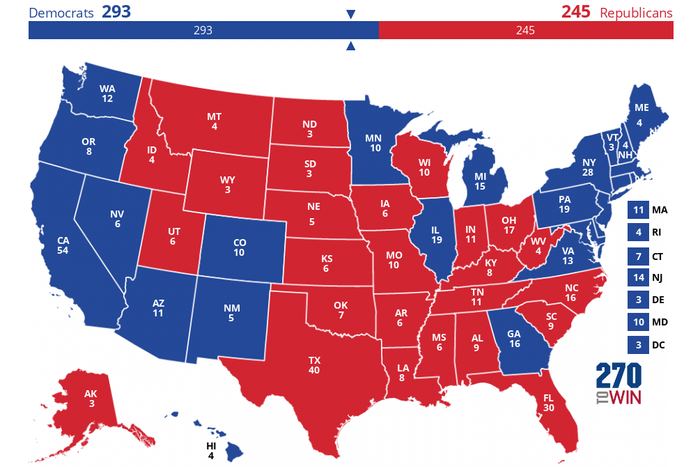

Looking at likely 2024 battleground states, Democrats won the top 2022 statewide contests (either senator or, if no Senate race was on tap, the governorship) in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, and Pennsylvania. Republicans won the top contests in Florida (arguably no longer a battleground state) and Wisconsin. Concede clearly red and blue states to their respective parties, and these trends would give you a 2024 presidential election map in which Biden wins 293 electoral votes, 13 less than he won in 2020 (the losses attributable to Wisconsin going red and to net red-state gains from the decennial reapportionment of House seats).

We’ll obviously have a better idea of what’s going to happen as 2024 approaches, factoring in whatever is going on in the economy or public health; the identity of the Republican nominee and the collateral damage if there is a highly competitive primary contest; and whether Biden can avoid a primary challenge himself. It’s entirely possible, of course, that the president, who will be nearly 82 on Election Day 2024, will decide to pack it in, creating wide-open races for both party nominations. But at this point, it’s fair to say that 2022 was a good sign for Democrats’ 2024 prospects.

More on politics

- What We Learned From the House Ethics Report on Matt Gaetz

- Everyone Biden Has Granted Presidential Pardons and Commutations

- Trump Is Threatening to Invade Panama, Take Back Canal