Hannah Puckett loves McDowell County. The 21-year-old college student has lived here in southern West Virginia her whole life, and if she has her way, she’ll spend the rest of it here, too. But during her lifetime, the county has lost a third of its population. Stroll through the center of Welch, the county seat, and you’ll see one boarded-up storefront after another. “People will start up businesses, and they’ll struggle to last a year,” she says. One by one, her childhood friends have been leaving, she says: “Everyone my age says that this county is dying.”

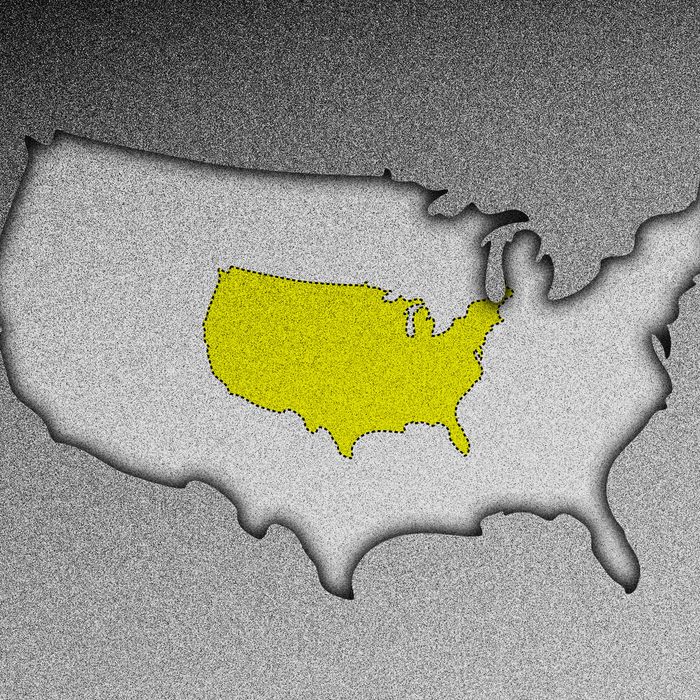

In a way, McDowell County is slipping backward in time. It’s the fastest-shrinking county in the fastest-shrinking state in the union with a population that’s now the same size it was when William McKinley was president. But in another sense it might be ahead of the curve — as a harbinger of America’s demographic future. New Census Bureau data released at the end of December shows that the population of the U.S. grew just 0.4 percent in 2022, which is better than in 2021 but worse than every other year of the past hundred years. If current trends continue, the nation could follow West Virginia into demographic shrinkage.

There are three major factors at work. Life expectancy is falling, birth rates are dropping, and immigration has been low. Government policies that could improve the situation have been inconsistent. And if we can’t grapple effectively with the underlying causes of a shrinking population, we could wind up with a country that is economically fragile.

Here, what’s behind the trends — and what we might be able to do to change course.

The Baby Bust

For a population to stay the same size, the average woman needs to have about 2.1 kids. We’re nowhere near that now. While the U.S. fertility rate was 3.6 in 1960, it fell below replacement level in 1972 and hovered just below it for the next 35 years. Then it started to fall again and is currently around 1.6.

Once upon a time, a fertility rate this low would have been seen as a godsend. Paul and Ann Ehrlich’s 1968 book, The Population Bomb, warned that world growth rates at the time would inevitably lead to a Malthusian nightmare in which “hundreds of millions of people will starve to death.” It was to avoid such a scenario that in 1980 China decreed that couples could have no more than one child each.

Soon after, however, demographers realized that not only were the Erlichs’ predictions wrong but that the world was heading for the opposite problem. Birth rates were falling so quickly that population growth was stalling. By 1995, Germany, Japan, and Italy all had fertility rates below 1.5. In 2016, China scrapped its one-child policy and started to encourage women to have more kids, though the fertility rate has remained stubbornly low, and by 2050 China is expected to have 100 million fewer people than it does today.

True, some countries remain highly fertile; in Niger, the country with the highest birthrate in the world, the fertility rate is 6.7, but even there it is falling. While the world population crested 8 billion for the first time last month, demographers expect that it will stop growing later in the century and decline thereafter.

Why are women having fewer children? As they gain access to education and jobs, they have alternatives to raising kids. When they do have kids, they want to have achieved some financial and career stability first, so they tend to have them later. In the U.S., women with a master’s degree have their first child six years later than women who have only a high-school diploma.

While national economic development tends to drive birthrates down, once a country achieves a certain level of prosperity, the relationship between prosperity and fertility flips and better-off individuals have more kids. One 2013 study found that a $100,000 increase in value of a U.S. family’s home boosts its probability of having a child by 16 percent. Anyone who’s raised kids will understand why; they’re expensive. According to a recent analysis conducted by the Brookings Institution, it costs about $17,000 per year to raise a child in the U.S.

Economic inequality is certainly taking its toll on West Virginia, the state with the fourth-highest poverty rate. “I’d like to have three kids,” says Puckett. “But I can’t imagine trying to bring a child into the world with the economy the way it is. I’m scared I couldn’t give them an education and a house to stay in.”

The pandemic, and all the economic uncertainty that entailed, made the prospect of having children even more daunting; it’s been estimated that 40,000 babies weren’t born that otherwise would have been. As the pandemic has receded, U.S. birth numbers have rebounded somewhat, but they’re still low by historical standards, and in the years to come, they’re expected to fall. Sometime in the 2040s, the Congressional Budget Office expects, deaths will outnumber births, as they already do in half of all states.

Fewer births don’t just lead to a smaller population but to an older one, since the younger cohorts aren’t large enough to balance the older ones. Since 2000, the median age in the U.S. has grown by 3.4 years to 38.8. By 2034, the number of Americans over 65 will exceed that of children under 18.

That means in time, ever-fewer working-age Americans will be supporting a steadily growing population of retirees. And there are other, less tangible, effects of an aging population, too. “A younger population makes us more vital, more innovative,” says William H. Frey, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

The Shrinking American Lifespan

After increasing steadily for 150 years, U.S. life expectancy started to fall again in 2019. Put another way, the average child born in that year could expect to live to 79; today, it’s 76. The decline is even more striking when you compare our figures with those of peer nations. In Germany and the U.K., life expectancy is 81; in Canada and France, 82; in Japan, 85.

Though we spend far more per capita on health care than any other country in the world, the problem is that it is distributed so unevenly. And that there are so many features of life in America that lead to shortened life spans, including lack of universal, affordable health care; high rates of gun deaths (suicides and homicides); and a raging opioid epidemic that has taken the lives of at least 1 million people this century.

West Virginia has the highest rate of opioid-related deaths in the country and the second-lowest life expectancy — just 74.5, the same as Guatemala. “When we look at the most significant factors with respect to life expectancy, many of them are rooted in socioeconomics,” says former New York City health commissioner Dave Chokshi, “by which I mean all of those factors that contribute to whether someone is healthy or not, factors like structural racism, which hold back minoritized groups, particularly Black Americans and Native Americans.”

The Immigration Drop-Off

The U.S. has the greatest number of foreign-born residents of any country on Earth: 48 million, or 15 percent of the population. As recently as 2016, we were gaining more than a million net immigrants a year, but the number has fallen ever since.

The reason for the decline defies easy explanation. There is, of course, the shift from the relatively pro-immigration Obama administration (which introduced DACA, smoothing the path to legal residency for children who had been brought to the country without documentation) to the Trump administration and its crackdown at the southern border and ban on citizens of seven majority-Muslim countries from entering the U.S.

Another factor is the pandemic, which the Trump administration used to justify an almost total closing of U.S. borders to asylum seekers under Title 42. The sharp recession that year also quashed demand for workers of all stripes but especially immigrants. In the second quarter of 2020, unemployment among foreign-born workers hit 15.3 percent, three percentage points higher than for native-born workers.

“When it comes to demographic decline, I think there’s a lot of reason to believe that immigration is a really important part of the solution,” says Danilo Zak of the nonprofit advocacy group the National Immigration Forum. He points out that immigrants tend to be younger than the average American, more fertile, and less likely to need public assistance. “We’re just looking much healthier demographically if we increase immigration.”

The Road to Rising Population

Taken together, the three trends driving U.S. population growth downward are self-reinforcing. A nation with a low birthrate and low immigration shrinks and gets older; an older, smaller population produces a less vibrant economy; a weaker economy attracts fewer immigrants and makes it harder for young people to have kids. Some fear this dynamic could produce a negative-feedback loop that’s impossible to escape, as Elon Musk tweeted in August: “Population collapse due to low birth rates is a much bigger risk to civilization than global warming.”

Few professional demographers believe the situation is as dire as that. But the issue is urgent enough that policy-makers are taking note. Numerous countries in Europe have adopted policies aimed at boosting population numbers, and some states have too. In West Virginia, the state offers up to $20,000 in cash to workers willing to move there and stay for at least two years. The program, called Ascend West Virginia, hopes to attract more than a thousand new residents over the course of five years. But so far it hasn’t worked out too well with just 86 workers relocated in the first two years.

A more effective approach would be to encourage parents to have children through policies like guaranteed paid family leave, child care, health care, and tax credits. In 2007, Germany, then grappling with the lowest birthrate in Western Europe, instituted a sweeping set of pro-family policy changes that included a full year of fully paid parental leave. In the aftermath, the fertility rate climbed from 1.4 to 1.6. The Biden administration has made its own efforts along these lines. In 2021, it worked to secure passage of the $3.5 trillion Build Back Better bill, which would have included hundreds of billions of dollars for child care, preschools, and child tax credits. But the bill died in the Senate.

A separate strategy would be to bolster immigration. Rural areas like McDowell County stand to benefit especially from humanitarian resettlement. “Refugees tend to settle in less dense population centers where housing is a bit cheaper,” says Zak. “And the interesting thing is that it doesn’t require changing our immigration system per se. It just requires making sure that our system is working at its full capacity.” In 2022, the U.S. ceiling for refugees was 125,000, but only 25,000 were admitted.

Under the Biden administration, the net inflow of immigrants has rebounded nearly to pre-Trump levels as the pandemic-shuttered economy reopened. The U.S. could be doing better, but anti-immigrant sentiment remains a potent political force in this country. Republican appointees on the federal bench have repeatedly thwarted Biden’s efforts to remove Trump’s Title 42 restriction, which could bring thousands of people into the country every day.

A third way to boost the population would be by helping people to live longer. One recent study found that if the country adopted a slate of policies like gun safety and environmental protection, some 200,000 lives a year could be saved. Probably the biggest single policy improvement would be to spread our massive health-care spending around more evenly. “I’m a proponent of universal health care. It could have a big effect,” says Chokshi. “We need a system that actually produces health.” Of the 15 countries with the longest life expectancy, all provide universal health care.

Population decline is a lot like global warming: It’s abstract, it seems far off, it’s easy to imagine that it won’t happen or that maybe its effects won’t be so bad. It’s also alike in that solutions can require a long time to take effect and that many politicians are staunchly opposed to most of them, especially conservatives.

West Virginia is a case in point. It’s a deeply red state that voted for Trump in 2020 by nearly a 40-point margin; its two members of the House, both Republican, continue to fight immigration and the kind of social spending that could revive population growth.

The problem isn’t all on one side of the aisle, though. Enough centrist Democrats oppose growth-friendly policies to thwart ongoing efforts to put them in place. It was the defection of a single Democratic legislator, for example, that killed billions for child care. And who was that renegade? None other than Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia.