Kyrsten Sinema believes that private-equity billionaires should pay a smaller income-tax rate than public-school teachers, that Medicare should not have broad authority to negotiate lower drug prices, and that America’s corporations and high earners should enjoy historically low rates of taxation in perpetuity.

Aside from this affinity for low taxes on investors and high profits for Big Pharma, the Arizona senator is a fairly ordinary Democrat. On the “culture war” issues that polarize America’s major parties — e.g., reproductive autonomy, LGBTQ+ rights, gun control, and immigration — Sinema is consistently (if moderately) left of center.

By giving voice to the ideals of the forgotten Americans who believe that love is love, women’s rights are human rights, and hedge-fund managers deserve special tax breaks, Sinema has made our nation’s Congress more representative of its people — or so a recent column from The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf would lead one to believe.

In an article titled “The Senate Needs More Kyrsten Sinemas,” Friedersdorf argues that the newly independent senator is making “Congress more representative of America.” He does not show that Sinema’s issue positions or voting record align her with a substantial but underrepresented segment of the electorate. In fact, he does not engage with the substance of her politics at all. Rather, Friedersdorf’s celebration of Sinema is based entirely on her decision to identify as an independent despite the fact that she actually represents one of the most overrepresented constituencies in Congress.

His argument goes like this: Although between 35 percent and 50 percent of Americans identify as independents, only 2 percent of U.S. senators identified that way before Sinema’s decision. This “glaring disparity between the proportion of independents in the population and their numbers in Congress” is likely “contributing to a loss of faith in Congress as a representative democratic institution.” Therefore, to reduce polarization, increase social trust, and render Congress more representative of the public, we need more senators to emulate Sinema’s example.

But as Friedersdorf acknowledges, Sinema’s rebrand is primarily a means for preempting a primary challenge. In her short time in the Senate, Sinema has managed to alienate an extraordinary share of her ostensible base. One recent poll from Civiqs found that 80 percent of Arizona Democrats disapproved of Sinema. A survey from Morning Consult, meanwhile, found Sinema enjoying a less catastrophic — but still perilously weak — 46 percent approval from her state’s Democrats. Last year, a Data for Progress poll of a hypothetical primary race between Representative Ruben Gallego and Sinema found the former prevailing by a 74-16 margin.

These poll results indicate that Sinema has not merely alienated her party’s progressive voters but also a great number of moderates. As of 2020, only 47 percent of Democratic voters identified as liberal, and there’s no reason to believe that that share is substantially higher in Arizona, a state that still votes to the right of America as a whole.

Thus, Sinema’s problem isn’t that she dared to prioritize the median voter over her party’s ideological extremists. Rather, her problem is that she has treated her constituents with contempt while pandering to deeply unpopular special-interest groups. Sinema hasn’t only bucked her party’s stakeholders on key votes; she has also made little time for soliciting their views or responding to their concerns. A former aide told the Daily Beast last month that Sinema limited “all meetings with constituents in her D.C. office” to a “half-hour period on Wednesdays,” giving each group roughly three minutes of face time. That is consistent with reports from local Democratic groups in Arizona, which say that “Sinema has rarely engaged with them, declining to hold large public town halls or meetings with state party figures.”

At the same time, Sinema has consistently refused to explain her dissents from party orthodoxy in public. The senator never made a public case for her opposition to closing the carried-interest loophole. She simply forced her party to kill Joe Biden’s tax proposal behind closed doors.

All this has left Sinema with little hope of winning a Democratic Senate primary. She has therefore concluded that her best bet is to preempt one: By registering as an independent, Sinema is telegraphing her willingness to run a third-party spoiler campaign if any Democrat dares to challenge her in 2024. That could intimidate her party into lining up behind her.

Nevertheless, Friedersdorf sees this Machiavellian tactic as a democratic triumph.

There are at least two problems with his argument. First, the vast majority of America’s “independents” are actually partisans. Roughly 75 percent of self-described independents lean toward either the Democratic or Republican parties. And in their issue preferences and voting behavior, Democratic-leaning independents are barely distinguishable from generic Democrats, while Republican-leaning independents have broadly similar views to generic Republicans.

It is true that “people who agree with the Democratic Party on most issues but identify as independent for psychological reasons” are underrepresented in the Senate. But it is hard to see why we should care about that particular form of underrepresentation. And Friedersdorf provides no reasons for doing so since he fails to acknowledge (or perhaps to realize) that most independents are de facto partisans.

The second problem with Friedersdorf’s argument is that Sinema’s brand of heterodoxy is scarcely an underrepresented one.

Friedersdorf is certainly right that America’s two-party system leaves a great many voters without any natural political home. A substantial percentage of the U.S. population wants to reduce immigration and increase Social Security benefits. And yet, to my knowledge, there is not a single member of Congress who supports both of those positions.

But there is no reason to believe that Sinema’s ideological profile — generally liberal on social policy yet staunchly opposed to raising taxes on capital gains, corporate income, or high earners — is more prevalent in America than it is on Capitol Hill.

As of 2021, overwhelming majorities of the public believed that wealthy people and corporations do not pay their fair share in taxes.

Sinema’s support for the carried-interest loophole, which enables hedge-fund managers to pay a 20 percent tax rate on their labor income, puts her to the right of Donald Trump ca. 2016. Indeed, even standard-issue Republicans generally decline to defend the carried-interest provision publicly since its sole constituency is rich Wall Streeters.

Similarly, Sinema’s opposition to Medicare negotiating the prices of most prescription drugs is deeply unpopular. In 2021, the Democratic data firm Blue Rose Research ran rigorous message tests on nearly 200 issue positions. The most popular, by far, was letting Medicare force down the price of prescription drugs.

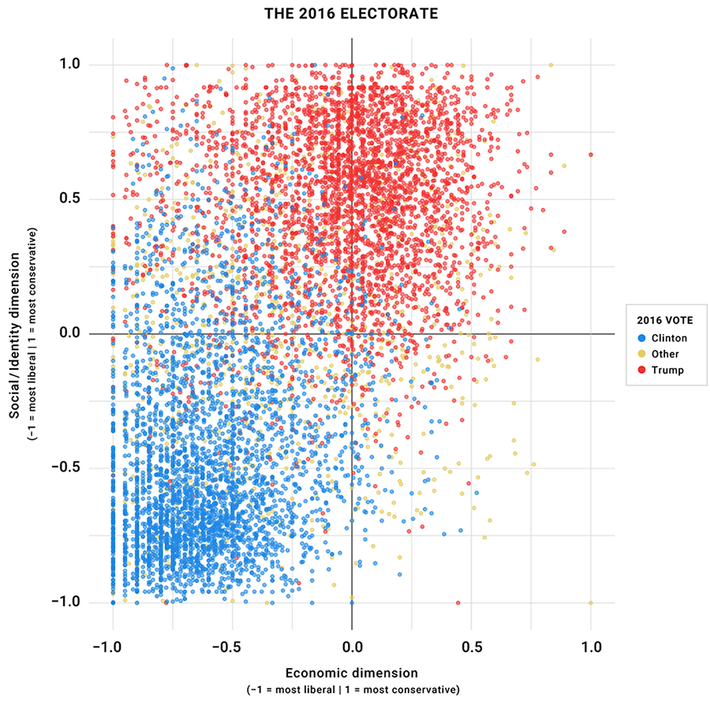

As a general matter, liberal on social issues but regressive on taxation and drug pricing is arguably one of the most overrepresented political tendencies in the United States. Congress is almost exclusively populated by Americans with elite levels of education and income. And political-science research has consistently found that the highly educated are more social liberal than those without college diplomas, while high earners are more economically conservative than the less affluent. A famous study of the 2016 electorate by Lee Drutman found that the percentage of voters that year who held right-of-center views on economic matters and left-of-center ones on “identity” issues was 3.8 percent. The truly underrepresented faction in U.S. politics, per Drutman’s analysis, held the opposite of Sinema’s views, favoring both conservative social policies and higher taxes on the rich:

If Sinema’s brand of independence doesn’t make Congress more representative of the electorate, it also seems unlikely to increase public trust in government. After all, in recent years, polls have found bipartisan majorities of voters saying they believe the wealthy and well-heeled interest groups have too much influence over politics. It is hard to see how a senator who frequently prioritizes the preferences of private equity and Big Pharma over public opinion improves that state of affairs.

To be fair to Friedersdorf, it is true that some U.S. voters lack strong ideological beliefs and have a general aversion to partisan acrimony and an affinity for bipartisan cooperation. Friedersdorf argues that, by forming their own independent caucus, ten moderate senators could please this constituency by forcing bipartisan compromises on key issues — which is plausible enough.

But in actual substance, this hypothetical doesn’t look much different than the status quo. Senate moderates have spent much of the past three years banding together to pass bipartisan legislation. Since Biden took office, the Senate has passed bipartisan bills investing in infrastructure, promoting domestic semiconductor manufacturing, enshrining same-sex marriage rights, and expanding criminal background checks for gun purchases, among other initiatives. To her credit, Sinema played a leading role in some of these deals.

Nevertheless, this raft of bipartisan legislation has done little to restore popular faith in government or reduce partisan acrimony. Seeing Sinema and Mitt Romney shake hands has not made America’s atomized and civically detached electorate feel less alienated from its government nor has it tempered the fundamental disagreements between red and blue America over reproductive freedom, gender identity, racial inequality, or immigration.

Perhaps all this would have turned out differently if only every moderate Republican and Democrat had called themselves an “independent” while negotiating their bipartisan bills. But Friedersdorf provides no reason for believing that since he doesn’t recognize that the Senate is already producing bipartisan legislation with regularity.

All this said, it is very plausible that Democrats in red states would be well advised to start calling themselves independents since doing so may marginally increase their support among truly nonpartisan voters at no actual, substantive cost to the Democratic agenda. Jon Tester might have a slightly better chance of surviving 2024 with an I next to his name.

But to believe that such superficial gestures could heal our polity’s maladies is to misdiagnose the latter. And to think that Sinema’s brand of politics gives voice to the unheard is to mishear the voiceless. Our democracy could use more of many things, but champions of the carried-interest loophole who rebrand as “independents” to escape democratic accountability isn’t among them.