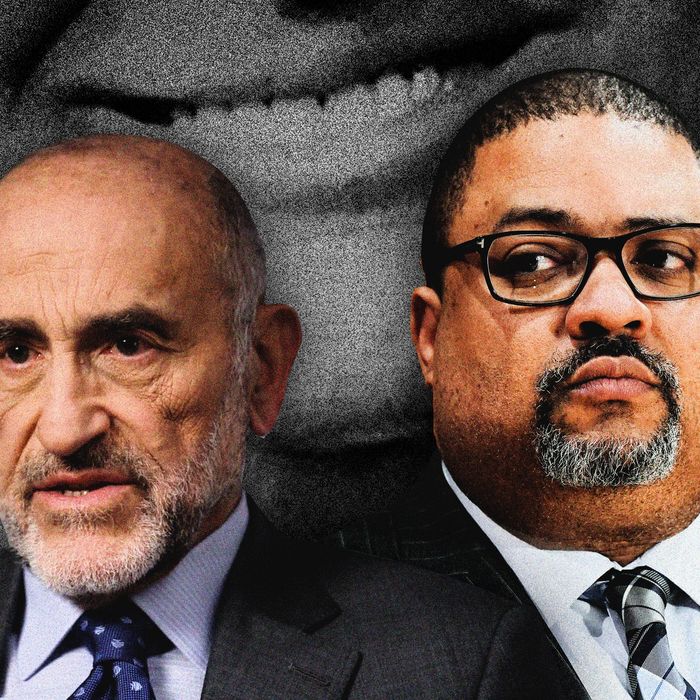

On Sunday evening, Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg gathered with several close advisers on the eighth floor of the office’s Chinatown headquarters to watch a 60 Minutes interview with Mark Pomerantz, who had led the DA’s investigation of Donald Trump. In his new book, People vs. Donald Trump, he takes Bragg to task for refusing to green-light criminal charges against the former president early last year. Bragg and his advisers had little idea what he planned to say ahead of the book’s release days later, though they had been on the receiving end of his criticism for the better part of the past year.

Pomerantz had been enlisted by Bragg’s predecessor, Cy Vance, in early 2021 to come out of retirement and help determine if Trump’s financial dealings broke the law. But last February, Pomerantz and a second lawyer, Carey Dunne, ignited a media firestorm when they resigned following Bragg’s decision. Since then, senior officials in the DA’s office had come to believe he selectively and misleadingly leaked information to the press, including his resignation letter, in order to damage the then newly elected DA. (Pomerantz writes that he “never” spoke “to the press at all during my tenure with the district attorney’s office,” but he is conspicuously silent on whether he spoke to the press after he resigned, which he did.)

The account of Pomerantz’s time in the DA’s office, in both his book and his appearance on 60 Minutes, is incomplete and misleading in important respects, according to several sources who are familiar with the investigation and the key events and who provided me with details about the office’s internal deliberations, as well as access to certain documents, in order to substantiate their account. At worst, the sources argue, his version of events is inaccurate and disingenuous on key points, and it risks both misleading the public and undermining any future criminal case that the office might bring against Trump. (Some disclosures: I used to work at the same firm as Pomerantz before he retired but did not know him well; I interned for Bragg in law school and have maintained a cordial relationship with him since.)

Pomerantz has claimed that he had a strong case against Trump but that Bragg wanted something that was effectively perfect. The truth is that Pomerantz had not developed a particularly good case against Trump by the time he was clamoring to criminally charge the former president last year, and his claim that Vance authorized him to indict Trump is highly suspect. There were also major outstanding legal and factual questions that could — and should — have been resolved before Pomerantz tried to force Bragg’s hand. He had also not completed the necessary legal spadework Bragg and his advisers repeatedly asked to see — including the difficult work of presenting a fully baked proposed case to Bragg, complete with a draft indictment and robust supporting legal analysis — that prosecutors are routinely asked to complete in complex cases.

“I’m proud of the time I spent as a Special Assistant District Attorney, and our team’s investigation into former president Trump,” Pomerantz said in a statement. “During that time I worked in close coordination with District Attorney Vance and the other members of our team, and looked forward to carrying on under his successor, District Attorney Bragg. I was disappointed with the decision not to move forward, and I wrote [the book] because I felt it was in the public’s best interest to know what happened. I stand by everything I said in my book.”

The dispute has become uncomfortably bitter and personal, but it provides us with rare insight into one of the country’s most closely watched criminal investigations. The story of how Pomerantz’s effort to indict Trump unraveled is ultimately not as simple or tidy as he has chosen to present it: an inexperienced and timorous DA letting an unrepentant and powerful criminal off the hook. Much of it comes down to legitimate disputes about subtle but important questions of law and investigative practice — many of which Pomerantz dramatically simplifies in his telling — as well as clear blind spots on his part. That is particularly true when it comes to his inability to garner the respect and trust of career prosecutors in the office and his unwillingness to critically assess the performance of Vance himself, who bears far more responsibility for this mess than Pomerantz is willing or able to acknowledge.

To many outside observers, Pomerantz’s arrival at the DA’s office in early 2021 was a major turning point in the office’s long-running investigation of Trump. He was nearly 70 years old and enjoying retirement after multiple stints as a federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York, most recently in the late 1990s, and working as a criminal-defense lawyer in the private sector. At the time, Vance’s office had been investigating Trump’s finances in earnest since mid-2019, and the decision to enlist Pomerantz to run the investigation provided some rare hope to many of Trump’s antagonists, who thought that the office might finally indict Trump and deliver some measure of justice to someone they regarded as an obvious crook.

In Pomerantz’s telling, the team working under his and Dunne’s supervision had compiled robust evidence that Trump had systematically overvalued his assets in order to obtain loans from banks, and they were ready to make the momentous decision to charge him in late 2021. Furthermore, he claims that Vance authorized them to indict Trump on this theory. All of this is highly questionable — both according to the sources who spoke to me and even Pomerantz’s own account when read closely.

In fact, by the fall of 2021, the prosecutors on the team working on the investigation were complaining among themselves and to supervisors that Vance and Pomerantz were trying to move far too quickly to an indictment of Trump without completing the necessary fact-gathering work and legal analysis. Over the summer, the office had indicted the Trump Organization along with the company’s CFO, Allen Weisselberg, and Vance was making comments both in the media and internally about his intention to make a charging decision about Trump before he left office at the end of the year. The prosecutors felt the case being developed had serious flaws both factually and legally that required additional time and investigation to fully vet.

Pomerantz’s book acknowledges that there were concerns on this front, but according to one of the sources, members of the team repeatedly raised “other concerns related more specifically to Mark and his lack of understanding of New York law.” White-collar law in the state is notoriously outmoded and convoluted — prosecutors in the state have been complaining about it for years — and it has more stringent requirements than federal law on some points that would have been central to a criminal case against Trump along the lines Pomerantz was contemplating, including whether it would have been necessary to show that Trump’s alleged misconduct had caused some form of financial loss to the banks. “He obviously knew federal law,” the source noted, “but that is different than New York law,” and Pomerantz “would get irritated” when people in the office tried to explain some of those significant points of differentiation.

Some prosecutors also bristled at Pomerantz’s handling of witnesses and felt that he was far too eager to levy a serious criminal charge against Trump. Among other things, they believed that he inappropriately tried to “lead” witnesses during questioning to provide him with answers to questions that he wanted — answers, in other words, that would implicate Trump in serious criminal conduct. Pomerantz’s book provides no indication that he ever learned about these concerns, but they were real and they cast serious doubt on his claims about what witnesses like Michael Cohen actually told him about Trump.

By September, the discontent was so great that a group of prosecutors on the team took their concerns to Dunne in a meeting over pizza — Pomerantz was not invited — and Vance eventually had to intervene in order to try to quell the uprising. In a meeting later that month, Vance assembled the full group investigating Trump. He insisted that he was keeping an open mind about whether or not Trump should be charged and said there was no deadline for making a decision, notwithstanding his departure at the end of the year.

Vance also told the group that, by that point in late September, there were still major outstanding questions about whether and to what extent Trump’s bespoke financial statements could form the centerpiece of a fraud case against him. “I realize that open questions still remain on some of our other investigative issues,” Vance said, according to one person present, “but the fact is that the question of the financial statements is the last and biggest of the allegations we need to look at.” Among the issues to be resolved were whether Trump had been personally involved in devising the alleged misrepresentations to banks, whether the banks had relied on the alleged misstatements, and whether the false statements had caused any actual financial harm to the banks, particularly since they may have given Trump the loans he was seeking anyway. These were highly significant issues under New York law that career prosecutors believed (correctly) that they needed to resolve in a careful and thorough way. But in the months that followed, Pomerantz would repeatedly insist that their concerns were overblown.

Vance’s effort to right the ship did not succeed. Four prosecutors quit the team, and things got so bad that even in the weeks after Bragg took office, he found that it was difficult to enlist other prosecutors in the office to join the investigation because it would require working with Dunne and Pomerantz, whose reputation among the team had by then become toxic.

As Vance’s term wound down in the final months of 2021, the office convened an outside group of former prosecutors to discuss the possibility of charging Trump. They were Greg Andres and Michael Dreeben, both of whom had worked on Robert Mueller’s Trump-Russia investigation; Scott Muller, a former federal prosecutor and general counsel at the CIA; Rick Girgenti, who was the only member of the group who had actually worked in the DA’s office before; and Harris Fischman, a former prosecutor in the Southern District of New York. They met for several hours on December 9, with Vance himself in attendance. This was not styled as a meeting in which the participants would definitively resolve whether the office should charge Trump, but if Pomerantz and Dunne could get the group’s support, it would have been an undeniable endorsement of their work. Prior to the meeting, Dunne had circulated documents that included potential language for a single criminal charge against Trump — a “scheme to defraud” under New York law — and what he described as “a detailed outline of the legal and factual arguments” that would likely be advanced by the defense in response.

Things did not go as they might have hoped during the meeting. For one thing, the presentation that Pomerantz and Dunne provided fell far short of what would have been necessary to convince anyone that there was a chargeable case against Trump. The package did not include the sorts of documents that prosecutors often prepare when they are close to charging a complex case and need to convince their supervisors that they should be allowed to pull the trigger. There was no draft indictment. There was no “prosecution memo” that would contain an internal description of the relevant facts and law, a candid discussion of the potential defenses, and, crucially, what the government’s response to those defenses would actually be if raised. Nor was there an “order of proof” that would identify the witnesses that prosecutors intended to call at trial, what those witnesses would actually say (based on interviews with prosecutors) to support the government’s case and satisfy the relevant statutory elements at trial, and exactly what documents the government would introduce and through which witnesses. These sorts of documents are vital not just for the people reviewing the investigative team’s work but also because the process of drafting them, which is time-consuming and laborious when done right, forces prosecutors to grapple seriously with the sufficiency and quality of their evidence in minute detail as well as the strengths and weaknesses of their proposed legal theories.

According to the sources who spoke with me, Pomerantz and Dunne never completed any of these documents before they quit last year — a striking omission that would seem to substantially undercut Pomerantz’s claim that there was a readily chargeable criminal case against Trump, if only Bragg had allowed him to bring it.

Pomerantz has long maintained that such a case was ready because Vance authorized him and Dunne to seek an indictment of Trump. The claim is based on conspicuously vague comments he attributed to Vance, including, crucially, some that Pomerantz did not hear himself and that were relayed to him through Dunne. On this critical point, he cites an email that he received from Dunne in mid-November 2021 in response to an email that Pomerantz had sent to Vance and Dunne that said that “[w]e need to make a ‘go/no go decision’ within the next few weeks” because their work was essentially done. Dunne responded that “Cy and I both believe that, if we had to decide now, it should be a ‘go’ decision.”

“That was never conveyed to the team,” one of the sources told me, while cautioning that it was at least conceivable that there were discussions among Vance, Pomerantz, and Dunne that were not shared with others in the office. “The authorization,” at least so far as the source could summarize, was to continue investigating. “It was never, ‘All right, go forth and indict,’” the source continued, “because there was nothing, there just wasn’t anything … There was nothing to indict.” If anything was expressed during this period, it was that “this would be a great civil case.’” Indeed, Attorney General Letitia James’s office brought such a civil case last year that largely followed the same outline.

As this was all unfolding in the final months of 2021, Bragg was headed toward election as the first Black district attorney of Manhattan. His transition team’s members tried to get access to Vance’s senior staff so that they could start to get read into the office’s ongoing work, including the Trump investigation. Contemporaneous emails during this period from Bragg’s inner circle suggest some frustration and confusion about why Vance’s staff were not being more helpful. They were not even aware of the December meeting with outside lawyers, despite at least one senior official in Vance’s office explicitly asking whether Bragg’s team should be allowed to sit in — after all, they would be stuck with any important decisions that might have been made in the meeting. It seemed like basic professional courtesy to let the incoming DA get a jump on managing one of the country’s most closely watched criminal investigations.

On January 5, 2022, days after he took office, Bragg would finally get a chance to see inside the Trump investigation. That day, he met with Pomerantz for what was supposed to be a short briefing that would provide him with enough information to speak with the press if he needed to answer questions about the investigation. But the session grew tense when Bragg started asking pointed questions about the investigation and the evidence that had been uncovered.

Bragg posed even more probing questions at a follow-up meeting with Pomerantz a couple weeks later. The questions that he raised in that meeting had been spurred in part by an internal memo written by a career prosecutor on Pomerantz’s team that was sent much to his anger. It addressed a rather important subject: Trump’s personal involvement in the scheme to overvalue his assets. The memo raised serious questions about the strength of the evidence concerning the extent of Trump’s personal involvement in the preparation of the statements. Bragg wanted to hear more. “I’ve read this memo,” one source recalled him saying. “It seems really thorough. What’s the response?” Pomerantz quickly grew agitated and, according to a source, shot back: “She never should have written that memo. She wasn’t authorized.”

Then came even more cause for concern. Bragg and his senior advisers were given a separate memo that concerned two similarly important issues — whether charges against Trump might be time-barred by the relevant statute of limitations and whether the office could establish that the alleged scheme had caused actual losses to the institutions that had received Trump’s financial statements. There were particularly serious concerns among prosecutors in the office on the second point. (In his book, Pomerantz insists that these concerns were overblown, but as a strictly legal matter, his defense on this point is not particularly compelling.)

Finally, Bragg himself asked Pomerantz and Dunne directly for a briefing on the five or so “best” misrepresentations and the proof tying each potential defendant to those misrepresentations. Over several meetings last January and February, according to the sources who spoke with me, Bragg and his advisers never received anything like the focused and detailed presentation that they wanted. Pomerantz in particular seemed to bristle at the questions he was getting, as if they were somehow beneath him to answer. As one of the sources put it to me, “They were not generally used to being asked substantive questions” by the DA when Vance was in charge. Bragg also asked for an order of proof, which never materialized.

Pomerantz was also pressed on who could actually testify that Trump participated in devising the alleged misrepresentations in his financial statements — as opposed, for instance, to other advisers doing so on his behalf. Pomerantz insisted that Michael Cohen could do it, but Bragg and his advisers were understandably skeptical given Cohen’s unusually heavy baggage as a witness — he had been convicted of lying to Congress, he clearly hated Trump, and he never shuts up, which means that there are reams of public statements that could potentially undermine his credibility at a trial. Though no one broached the matter with me directly, the concern about Pomerantz’s handling of Cohen as a witness may also have been at issue when prosecutors complained internally that Pomerantz was improperly leading witnesses during interviews.

Pomerantz was also frustrated by Bragg, and his anger boiled over by the end of January 2022. His book quotes a lengthy email that he sent Bragg one morning in which he tells the DA that he is “not happy … with the status of the Trump investigation and how you are handling it — or not handling it,” and that he and Dunne are “both ready” to quit. “We will leave, and you can deal with the resulting consequences,” the email continues, and Pomerantz tells Bragg that he “need[s] to respect our judgment, our decades of experience as prosecutors and defense lawyers, and the work that we have put into the case.”

Pomerantz acknowledges in his book that Bragg quickly and politely responded to this email, but it is far from clear that Pomerantz deserved any such indulgence. Like much of his book, the email that he sent to Bragg adopts a striking and undeniably awkward tone of arrogance and imperiousness on his part. Pomerantz blames Bragg — his boss — for not quickly cultivating a productive working relationship with him, but given the way that Pomerantz evidently felt comfortable speaking to him, the suggestion that Bragg is to blame for the rift is very hard to accept, to put it mildly.

In my discussions prior to the book’s release, it was clear that the sources were not comfortable speaking on Bragg’s behalf about a possibility that has bothered me ever since Pomerantz’s resignation — that Pomerantz’s overall handling of the situation, as well as the sympathy that he quickly received from some legal pundits after news of his departure broke, may have been influenced (intentionally or not) by the fact that he is white and that Bragg is Black. One source approached the subject with extreme delicacy, telling me, “I think some of the tone of what I have seen reported about what’s in the book, it’s just startling to me. I know that Mark would not have spoken to Cy Vance that way.”

By the end of last February, it was clear that Pomerantz would not get his way. Bragg informed him that he was not going to authorize a prosecution of Trump at that time and that he felt that there was additional investigative work that could be done. Pomerantz and Dunne then resigned.

Despite its flaws, Pomerantz’s account offers some valuable observations. He correctly notes that “[f]undamentally, the case” against Trump based on his finances “should have been investigated by the Department of Justice, not the Manhattan district attorney’s office,” and he rightly questions why the Biden administration under Attorney General Merrick Garland did not pursue it. His book also offers a serious argument, if slightly unfocused and meandering at times, about the need to hold Trump to the same legal standards as everyone else (even if Pomerantz himself seems unwittingly to have faltered on this point by offering a weak case that appears to have been heavily influenced by his view that Trump is a uniquely dangerous political figure). And he has identified some long-running problems in the DA’s office — including resource constraints that have historically prevented prosecutors from aggressively prosecuting financial crimes — even though, given the time period in question, the blame for this should fall squarely on Vance rather than Bragg, who had just entered office after campaigning on increasing the office’s commitment of resources and enforcement efforts in precisely this area.

In a perverse way, Pomerantz’s self-aggrandizement and fixation on his treatment threatens to obscure a variety of much larger problems with his account. It is not clear at all that Vance actually authorized an indictment of Trump, and there is considerable reason to doubt this self-serving claim, which might reflect wishful thinking on Pomerantz’s part — an evident desire, which courses throughout the book, to interpret events in the way that most closely aligns with his objectives and preconceptions.

Moreover, despite what Pomerantz may claim, he had not completed the necessary work — either substantively or procedurally — to indict Trump, and the case that he was contemplating had considerable challenges both legally and factually that Pomerantz seems incapable of fully appreciating or, more to the point, taking any meaningful responsibility for despite the fact that he was one of the people nominally at the helm of the effort. The book makes clear that he had not even settled on a proposed legal theory or set of charges, which is a prerequisite for any responsible prosecution, whether the case involves a former president or not. By itself, that fact seriously undermines Pomerantz’s claim that he had a case against Trump that could be responsibly charged.

In recent weeks, there have been news reports suggesting that Bragg’s office is considering the possibility of filing charges against Trump based on his payment of hush money to Stormy Daniels in the run-up to the 2016 election. It is unclear whether that will come to pass, but Pomerantz’s book, as other observers have already noted, will complicate any such effort and provide fodder for Trump’s defense by giving Trump ammunition to claim that the DA’s office is charging him to score political points and that Cohen, who would likely be a crucial witness in this scenario, is wildly unreliable — a self-evident point, perhaps, but one that could gain even more traction in a criminal proceeding now that Pomerantz has publicly aired high-level internal disputes on this point involving the sitting DA himself.

This would be deeply ironic considering Pomerantz’s stated interest in bringing Trump to some form of justice, but it is not clear that he particularly cares or even appreciates this. As a lawyer, he had an impressive career in public service over the course of his long life, but it is unfortunate for everyone involved — except, perhaps, Trump — that he chose to end it this way.