Dhiraj Arora had terrorized Fort Greene for years, but the campaign he launched on a warm January night in Brooklyn was remarkable even for him. Just after 2 a.m., he threw bottles at Evelina, a trattoria on DeKalb Avenue, smashing a large window. From there, he took aim at Izzy Rose in neighboring Clinton Hill, where a security camera captured him pitching shards of concrete through the cocktail bar’s large storefront window. He capped the night off by returning to Fort Greene, where he tossed a metal garbage basket into the window of the Great Georgiana, a popular gastropub on the corner of Dekalb and Vanderbilt. The next night Arora picked up where he left off, shattering a curtain of windows at Rhodora, an ecoconscious natural-wine bar a block away from Evelina.

“I immediately knew who it was because he’s been doing this for years,” said Giuseppe de Francisci, a managing partner at Evelina. “He’s trashing restaurants that have kicked him out.”

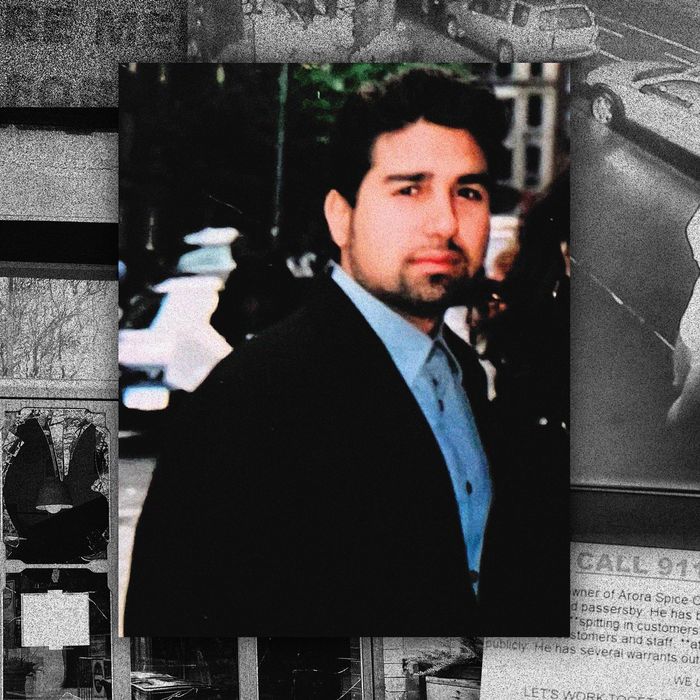

De Francisci isn’t the only business owner who has dealt with 47-year-old Arora before. It was the third time Arora had broken a window at the Great Georgiana in the last ten months. Employees at the Indian restaurant Dosa Royale had called 911 on him years earlier. He also broke a bottle at the feet of Treis Hill, the owner of Dick & Jane’s cocktail bar; threatened to burn a hostess at Evelina; slapped a manager at Saraghina Caffè in the chest; and harassed a bartender and guests at Izzy Rose. Arora’s incessant menacing has been so bad recently that someone posted a flyer urging anyone who saw him to contact the police. “Millionaire Menace Terrorizes Fort Greene” it announced in bold red letters above a mug shot of Arora.

Arora’s family says he’s no millionaire. Twenty years ago, he founded a company that rode the health-food craze by selling packets of Indian-spice blends in grocery stores across the country. In 2007, Crain’s named Arora one of the city’s top business owners, and a few years later the New York Post crowned him the “Spice King.” With his star on the rise, Arora lived the life of a swaggering playboy entrepreneur who spent extravagantly on clothes, travel, and restaurants. “I am the definition of passion,” he told a small magazine at the time. “Stay tuned.”

But Arora’s bluster masked his struggle with bipolar and alcohol-use disorders, a dual diagnosis that made it impossible for him to maintain his business. Over the past decade, his family and friends watched helplessly as his mental health declined, taking away the success he’d earned and sending him down a destructive path.

“His episodes have become far worse and more frequent, and now every time there’s an episode, all we can do is call the police,” said his sister, Puja Arora. “At that point he’s violent, he’s dangerous, he’s a threat to himself, he’s a threat to others. It’s this constant cycle. Every step of the way the system failed him.”

Arora’s family has seen him cycle in and out of hospitals, jails, and rehab facilities. Since 2019, he’s been arrested in New York, New Jersey, and Florida for stalking, harassment, menacing, criminal mischief, and more. His illness has confined him to a sort of systemic purgatory: Too sick for his family to care for, but not harmful enough for the legal system to intervene.

Meanwhile, his neighbors fear what the next episode might bring, a looming dread shared by many New Yorkers who say crime is the city’s top problem — including Mayor Eric Adams, who has blamed mental illness for the rise in subway crime in particular. In November, he announced a haphazard plan to allow first responders, including NYPD officers, to forcibly remove people from the streets and involuntarily hospitalize them. Members of the City Council ripped into that plan at a hearing in early February, saying the city can’t police its way out of a mental-health crisis.

Indeed, police haven’t made a difference when it comes to treating Arora’s own crisis or, until recently, preventing him from terrorizing people. Mental-health court gives defendants a chance to enter treatment programs as an alternative to jail or prison, but none of Arora’s cases appear to have gone through the court. It’s unlikely his crimes — mostly misdemeanors — would have qualified him for the kind of court-ordered supervised medical treatment that his family hopes might prevent further incidents. “People who do well in mental-health court are those who have significant challenges related to untreated mental illness and have committed a serious crime. If they don’t have those two things, then you don’t really have the mechanisms at play to respond to them,” said Jeff Coots, director of John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s From Punishment to Public Health program.

Arora and his sister grew up in Bridgewater, New Jersey, where she recalls he was “super-loving, protective, hysterical” before the onset of bipolar. “He was an athlete. He was voted best all around in high school, most likely to succeed. He had all the hot chicks.” Dhiraj received his bipolar diagnosis in 1997, the same year he graduated from the University of Michigan, and was in and out of hospitals for treatment.

After college, Arora moved back home and, inspired by his parents’ reputations as some of the best cooks in his family’s community, sold spice mixes he blended together at local flea markets. He gave his company a simple name, Arora Creations, and tapped into Americans’ growing desire for healthier organic ingredients in their everyday grocery stores. “Dhiraj has hands down one of the smartest, savviest business minds I’ve ever come across,” said a family friend who works in finance. The company operated with a few employees who worked out of Arora’s studio on Canal Street. By 2008, some 8,000 stores across the country, including Publix and Whole Foods, carried Arora Creations spice packets. “This isn’t a trend, this isn’t fat-free,” he said in a promotional video from the time. “This is a lifestyle. This is my culture. This is my tradition, my roots.”

As the company grew, so did its founder’s drinking and erratic behavior, according to those who knew him. In September 2011, Arora ran naked through the gym of the midtown Four Seasons Hotel while drinking tequila. “Suck my million-dollar cock,” he allegedly told police as they took him to St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital for a psychological evaluation. No charges were filed. The Post picked up on the story and, when a reporter reached Arora for comment, he offered a correction: It was “suck my $57 million dick,” he said.

The Post’s story was easy fodder for New York’s media blogs, nearly all of which ran gleeful posts about the incident. The Observer interviewed Arora over an alcohol-soaked lunch at the Breslin for a short profile that depicted him as an immature but charming — if a bit unhinged — impresario. A close friend speculated that Arora enjoyed the media attention the episode brought him, even if it was bad for business: The swaggering, yoga-practicing entrepreneur was a familiar trope in the 2010s, and Arora seemed happy to play the part.

Whatever high Arora might have felt crashed when, a few months later, one of the police officers who arrested him filed a $57 million lawsuit against Arora claiming he had assaulted her. The case was dismissed, but the negative publicity from the incident, along with Arora’s deteriorating mental health, virtually doomed his business and he filed for bankruptcy in 2014. He spent the next several years living in a small apartment in Fort Greene, drinking away what little money his business brought in.

When the pandemic struck in 2020, Arora moved in with his mother in New Jersey and tied together a few months of sobriety. For the first time in years, Puja felt like she had her brother back. “We went out to dinner two or three times a week, we went out for walks, we did things, we hung out the way we used to. Then he stopped taking his medicine and the cycle started,” she said.

Arora disappeared for days. Family and friends did what they could to help, loaning him money, bailing him out of jail, paying for lawyers and expensive treatment facilities. Occasionally, he would stick to medications to treat his bipolar disorder and stay away from alcohol, but the drinking would resume and he would quit taking medicine and spiral out of control. He’s been hospitalized more times than the family can count.

“He goes there, they drug him up, they keep him there for three days or two weeks, then he’s released, and that’s the problem. There’s no follow-up, he’s not mandated to attend any of his sessions,” said Puja. “It just feels unfair. He is insanely smart. He has the ability to do well in this world, and well for himself, but he needs help. He needs the compassion that we feel for other diseases.”

When he is not at home or in a hospital, Arora is often in the place his family fears most: police custody. Last February, the NYPD picked him up in the throes of another manic episode in lower Manhattan. Arora told police that he needed to go to the hospital because he didn’t have his medication. Arora was brought in handcuffs to the Mount Sinai Beth Israel emergency room where he said officer Blair Butler struck him in the head and cut open his ear so badly that he was stitched up in the ER. (Arora’s attorney, David Cetron, provided video of the incident.) The Manhattan District Attorney Office’s police accountability unit opened an investigation that determined it couldn’t prove criminal conduct on Butler’s part. The Civilian Complaint Review Board also opened an investigation but has yet to issue a recommendation.

While Arora’s family worries how he will be treated by officers who often have no training to deal with someone in a manic state, sometimes they have no other choice but to ask the police for help. This past June, Puja called 911 because she feared her brother would hurt her mother. Again, police took him to a hospital where he was admitted for psychiatric treatment. After he was discharged, police arrested Arora for a separate incident in which he’d dialed 911 and made a false report. He spent the next 89 days in jail. About a month after he was released, in October, he was arrested again.

In November, Prapti Patel, a 33-year-old consultant, was having drinks with a friend at Izzy Rose when she noticed a man throwing broccoli rabe at them. Arora had been hanging around the bar recently, even handing out spice packets to customers. Patel said she politely asked Arora to stop, but he became enraged and threatened to kill her. “He started calling me an Indian bitch and saying he hated Indians even though he was Indian,” Patel said, adding that she was so disturbed by the incident that she filed a report with the NYPD. Nothing happened, and Arora’s behavior took a sharp turn for the worse.

On January 14, Arora was arrested for allegedly refusing to pay for dinner at a sushi restaurant in Tribeca. Three days later, he was arrested again for menacing and criminal possession of a weapon when he threatened someone in downtown Manhattan. His mother, Chancal, bailed him out, showing up at a court hearing with an employee from Recovery Centers of America in the hopes of shuttling her son directly to the mental health and alcohol treatment facility near their home in New Jersey. They didn’t even have a chance. According to Chancal, Arora slipped out of the courthouse after he was released from custody. In an interview, Arora claimed he was sent to Bellevue Hospital for a psychological evaluation after the hearing and that by the time he returned to the courthouse, his mother and the recovery center employee were already gone. Regardless, Chancal was frustrated by the court’s unwillingness or inability to force her son into treatment, and she left uncertain whether she would see him before his next arrest.

A little over a week later, Arora went on his rampage through Fort Greene. Fed up, Evelina’s de Francisci posted a video of security-camera footage on Instagram, urging anyone who saw Arora to call the police. A few days later, one of Evelina’s regulars saw him in Soho and called 911. Arora was arrested and sent to Rikers Island. A grand jury charged him with two counts of felony criminal mischief and one misdemeanor.

Arora has yet to be arraigned on his most recent charges, but because of the severity of the charges and his lengthy criminal record, he now faces years in prison. “He’s committing criminal acts, but it’s more the result of mental illness than anything else. He’s a real pleasant guy when he’s on his meds, but when he’s off, he’s totally irrational,” said Steven Alan Hoffner, one of Arora’s attorneys. “He’s just sick.”

But some of Arora’s victims are unwilling to accept that premise. “I know people with bipolar disorder. The mood swings don’t transform people into violent monsters,” said de Francisci. “He’s the cause of his issues.”

During phone calls from Rikers, Arora defended himself by saying the Brooklyn business owners had previously antagonized him while also acknowledging his struggles with bipolar disorder and alcohol use. “You lose absolute control of judgment. Add the vodka and things get aggressive,” he said. He blamed his parents for not bailing him out of Rikers and getting him into a treatment program while he awaits trial.

Chancal said she can’t put together the money for her son’s bail and she’s lost faith in her own ability to keep him in a treatment program. She also knows her son has little chance of improving in one of the country’s most notorious jails where the mentally ill have been routinely abused by corrections officers and dozens of inmates have died from drug overdoses, suicide, and violence in recent years. She hopes, against all evidence, that the system will finally help her son.

“If somebody is having a heart attack in a restaurant, will the police take him to a hospital or a jail? Why is there a discrimination between physical illness and mental illness?” she wondered. “Dhiraj should be in a hospital.”