This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

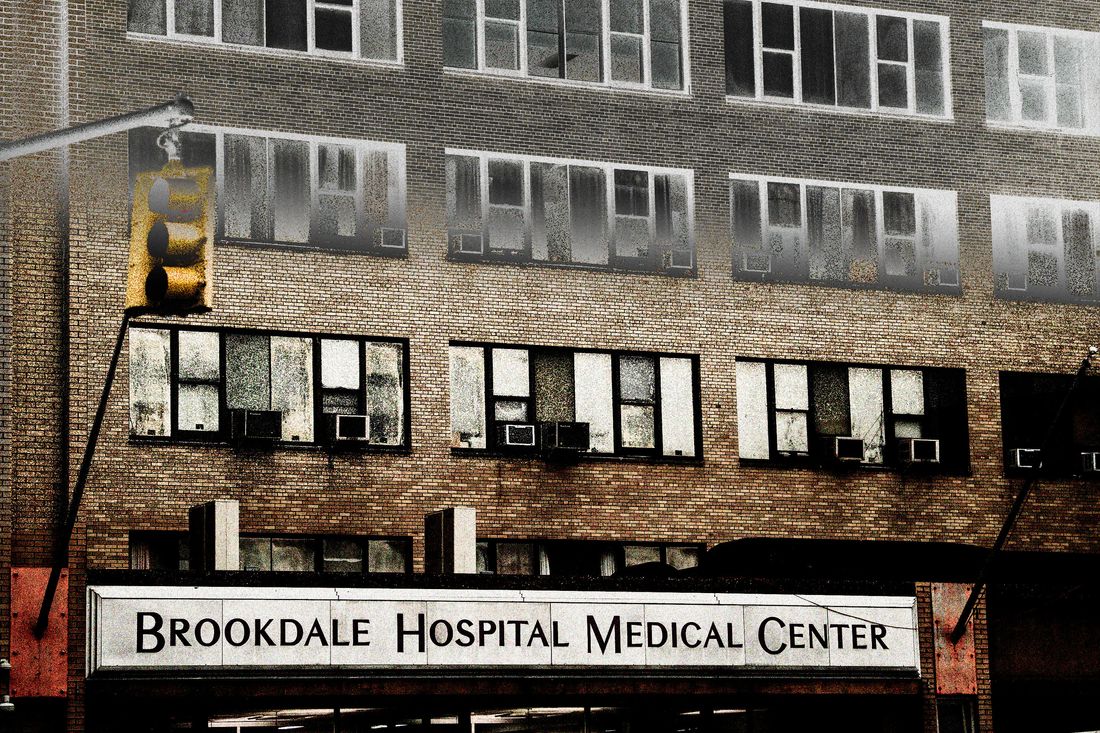

Terisa went into labor early on July 25, 2021. In the ambulance on the way to Brookdale Hospital in Brooklyn, she let the medical team know she wanted an epidural, figuring the birth might go pretty quickly; she had three children already. But from the moment Terisa and her partner arrived at the hospital, nothing felt the same.

In the labor-and-delivery center, the nurses asked her if she had to go to the bathroom. She didn’t, but they kept repeating the question. “Every time they asked me to use the bathroom, I asked for my epidural,” Terisa, who asked to be identified by only her first name, tells me. Their response — that they were waiting for blood work first — made no sense to her: That hadn’t been required before her other births, and anyway Brookdale had recently tested her blood as part of her prenatal care.

Eventually, Terisa agreed to the nurse’s suggestion of a catheter, but she never got the epidural. About an hour and a half after Terisa arrived at the hospital, her son was born in an unmedicated birth she hadn’t wanted. As she was being transferred to another room in a wheelchair, a nurse stopped her in the hall and told her not to breastfeed because she had tested positive for marijuana earlier in her pregnancy. “I was even more confused because I didn’t even know that I was tested before,” says Terisa.

Another nurse arrived and told her to pump breast milk but throw it away. “That’s when I found out they drug tested me in the birthing room,” she says. This, too, was a first — and something she hadn’t consented to. The hospital staff had gotten a consent form to test her for COVID-19 while she was in labor but not for a drug test. “I didn’t know who to trust at that point,” Terisa says. “I was doing a lot of research and Googling when I found out. Are they able to do this?”

The time right after birth is sometimes called the “golden hour.” Under ideal circumstances, it’s dedicated to bonding and skin-to-skin contact. Instead, still recovering from birth, Terisa was fielding a call from the New York City Administration for Child Services, or ACS. “I’m really getting scared because I’m in a vulnerable position,” says Terisa, who has brought a complaint before the New York State Division of Human Rights. “They could keep my baby and not let me take him home.” It turned out to be just the beginning of her ordeal.

Since Roe fell, New York City and State have advertised themselves as refuges for abortion patients living in hostile jurisdictions. But advocates say that’s not enough when even the use of marijuana, a legal substance in New York, has contributed to babies being removed from their parents. Family-defense and harm-reduction organizations have long sounded the alarm. Legal Momentum legal director Jennifer Becker, who is representing Terisa, points out that there’s a reproductive-justice argument against the practice too. Using pregnant people’s drug tests to trigger investigations by child-protective services is to “essentially accept the notion of fetal personhood,” Becker says, “because these are actions that a pregnant person is taking before there is a child.” Pregnancy itself becomes the basis for losing one’s rights. If a law-enforcement agency wants access to the blood-test results of someone who, for example, showed up at the hospital intoxicated, the Fourth Amendment requires it get a search warrant. “We’re not seeing that here because there’s an overlay of ‘child protection,’” says Becker.

In November 2020, the New York City Commission on Human Rights announced it would investigate three private hospitals for possible racial and ethnic bias after reports that “hospitals continue to use a single unconfirmed positive screen as a reason to report parents” to child services. The commission noted that, in New York City, Black women face a maternal-mortality rate 12 times higher than white women and that nationwide studies show they are far more likely to be drug tested “despite similar rates of drug use in both populations.” Several New York City agencies, including ACS and the Health Department, issued guidance around that time saying that “a positive toxicology result for a parent or a newborn, by itself, does not constitute reasonable suspicion of child abuse or maltreatment, and thus does not necessitate a report” to the registry to investigate child abuse. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t happening anyway.

It’s hard to know how many other Brookdale patients have experienced what Terisa did because there’s no official collection of drug-testing data, and as Becker points out, “a lot of pregnant patients and postnatal patients don’t know that this has actually happened to them” unless an investigation is triggered. Legal Momentum is hoping to obtain the hospital’s policies through litigation. Becker says that while marijuana is legal, “We have concerns about the practice no matter what.”

Terisa’s complaint against Brookdale and ACS before the Division of Human Rights alleges that she was discriminated against “on the basis of sex, pregnancy, race, and marital status.” (Terisa is Black and wasn’t married to her partner, whom hospital staff listed as the “putative” father on one of the documents.) She and her attorneys are requesting that Brookdale stop drug testing pregnant patients without their knowledge and consent, that it not prevent patients from “making informed decisions about breastfeeding,” that it cease reporting patients to ACS on the basis of drug tests, and that it retrain staff accordingly. An attorney representing Brookdale in the inquiry did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“By law, protecting privacy of families, we cannot share information about whether a family has a case with ACS, or case details,” an ACS spokeswoman said in an email. (The state office, also named in the complaint, said it could not comment on pending litigation.) But she noted, “By both state and local policy, neither a positive drug test of a parent nor a positive toxicology of a newborn baby, is in and of itself a basis for a determination that evidence of abuse or neglect exists. We are working closely with health professionals by helping hospitals and other medical staff understand the impact reporting has on families and that reports should only be made when there is a concern for a child’s safety.”

The day Terisa gave birth, the ACS worker wanted to talk to her and to see her baby over video chat. He also wanted to talk to her mother and her three older children, one of whom was only 2. According to Terisa, he peppered her children with questions about drug use, terrifying them that their mother would be taken away from them. “Whatever he was asking my daughter — she was 9 at the time — made her start asking me, ‘Mommy, can you stop smoking? Are you going to die?’”

“It was a lot going on at a time where I was supposed to be trying to give birth and just be a new mom again,” Terisa says.

The caseworker said she could choose an alternative to a formal investigation called the CARES program. “I felt like I was in a corner, so I had really no choice,” Terisa remembers. “But I said, ‘I’ll work with the man’ versus them trying to do things behind my back.” She hoped that by choosing the “voluntary” process, she might be free of ACS sooner. “It really didn’t happen like that,” she says. The process took 90 days. ACS came to her home the day she and her baby came back from the hospital, monitoring how she interacted with her children and telling her the apartment was too messy, necessitating the arrival of a cleaning crew she found invasive.

Terisa, still recovering from birth, was subjected to drug tests roughly every two weeks, as was her partner. It was traumatic. So was the fact that she blamed herself for her infant son’s slightly misshapen head, a common condition known as plagiocephaly. “I felt like, because I didn’t get the epidural, it was me that did it to him because I kept stopping” in order to cope with the pain, Terisa says. “Now his head is fine, but at the time I thought it was something that I did to him.”

And Terisa’s problems may not be over. Becker says a “continuing harm” is that, after the formal investigation, a person can move to have their records expunged if ACS determines that child abuse or neglect was not substantiated. Instead, because she chose the alternative CARES program, Terisa’s case stays in limbo and on her records. Seher Khawaja, another attorney at Legal Momentum, points out that Terisa is “in perpetuity listed as a drug abuser on her own medical records with the hospital as well as her newborn child’s records.”

Terisa started talking to another mother she knew who, she learned, had gone through a similar experience giving birth at the same hospital. This acquaintance recommended that Terisa request her medical records. Reading them, she realized that a nurse, whom she’d seen sneaking around her son, had been surreptitiously collecting a urine sample for a drug test. She also learned that ACS was called hours before even testing her son.

“I was reading through everything — I’m like, Oh my God,” she says. The medical records misrepresent what she remembers happening, accusing her of refusing to care for her baby when, as she recalls it, she turned down the nurses’ repeated offers to change and feed the baby because she felt patronized by them. “After a while, I felt like they were doing it a little too much, as if I couldn’t do it myself,” she says. The documents also claimed her son had been in the neonatal ICU, something that never happened. “I felt that they did that to excuse the drug-testing part,” Terisa says. “Because when I was reading up on it, when I was Googling, when I was supposed to be in recovery, it said they can only drug test for a medical reason.” The documents also said the test results were preliminary and needed to be confirmed, but that never happened either. She felt targeted. “They really wanted to see my baby get taken away,” she says.

At her six-week checkup, she sat in the waiting room and heard another mother talking on the phone about smoking marijuana. “I wanted so bad to tell her,” Terisa says, “that she was going to get tested.”

Becker, her lawyer, argues that, while the hospitals are claiming they’re doing this to help patients, “I don’t think we have seen in any of the cases that have come to us that hospitals have used any of this information to provide specialized medical care to either the mother or the baby.”

Medical providers collecting and passing on such information to child-protective services could actually do the opposite. As Lynn Roberts, associate dean of CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy, put it in response to the announcement of the Human Rights Commission’s investigation, “Hospitals should provide health care and supportive services without bias and not disrupt families nor deter them from seeking that care for fear of losing their children.”

Legal Momentum has heard from patients in states known for anti-abortion legislation — such as Tennessee, Mississippi, and Georgia — but also from people in bluer New York and New Jersey. A separate federal case was brought against a private hospital in Pennsylvania.

Says Khawaja, “I think at the heart of this case and so many of the cases we’re seeing is that hospitals are prioritizing what they see as the needs of the fetus over the rights and the needs and choices and autonomy of pregnant women.”