“Stop it!” Restive Ventures told the start-ups in its portfolio in an email at 3:30 a.m. ET Friday morning. “Silicon Valley Bank is not FTX, it’s not Luna, it actually has the money!” the San Francisco-based venture-capital firm wrote alongside an image of Bill Nye the Science Guy overlaid with “CALM. DOWN.”

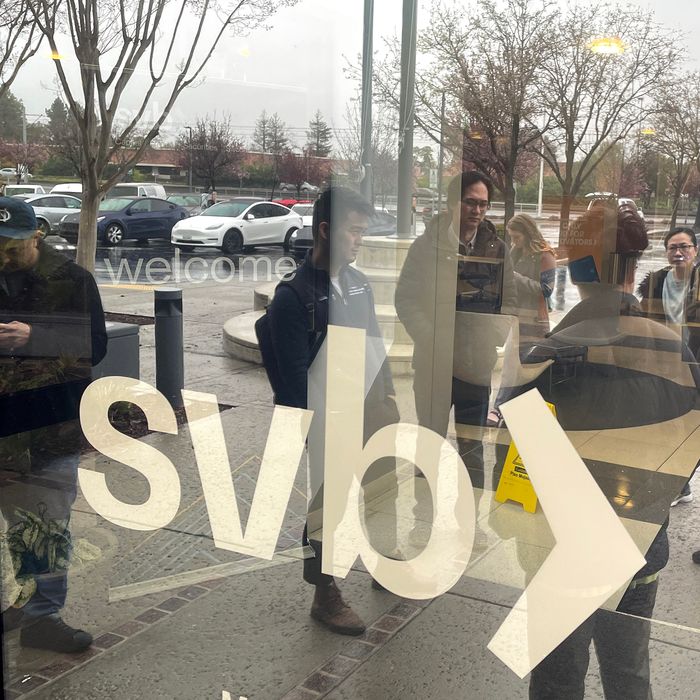

Restive, which invests exclusively in fintech start-ups, was trying to dissuade the founders it had funded from pulling their deposits out of Silicon Valley Bank, an iconic 40-year-old institution that has been a financial lifeline to start-ups turned away by Wall Street — sometimes their only one. But start-ups had begun pulling their money out after SVB’s stock price plunged 60 percent on Thursday, following a rather opaque announcement by the bank that it was trying to raise cash. The whole situation started to take on a feeling of déjà vu following the high-profile collapses of crypto exchange FTX and Silvergate, a crypto-focused bank that said it would shut down earlier this week, following depositor panics.

SVB, though, was much larger than those: Whereas FTX purportedly held (and should have actually held) about $10 billion in assets at its collapse, Silicon Valley Bank had more than $200 billion.

“We suspect that part of the problem here is that three completely different things are being conflated, if not intellectually, at least emotionally,” Restive wrote. Its pleas didn’t work. Some eight hours after Restive’s email, the FDIC said it was taking over SVB, which had stopped processing wire transfers; its stock never even opened for trading Friday. “We still stand by our view that this situation didn’t have to turn out this way,” said Tyler Griffin, Restive’s co-founder and managing partner, who said his firm had conducted its own thorough analysis of SVB’s financials and determined it was solvent and stable.

Of course, we live in a post-GameStop world, where facts and rationality matter less than the herd mentality of a social-media-driven contingent who can move markets. And the thing about bank runs is that they are, almost by definition, self-fulfilling prophecies: Even If Silicon Valley Bank was financially fine before the panic, if enough people worry that they ask for their money back at the same time, that can create major, even fatal, problems — and it did in this case. The death-spiral mechanics are not all that different from the Reddit mania a couple of years ago, when investors on the WallStreetBets forum who wanted the price of “meme stocks” like GameStop and AMC to go up made them go up by “YOLO”-buying them in bulk, putting certain short sellers out of business in the process. At some point, it didn’t matter anymore that GameStop’s earnings couldn’t justify its soaring valuation; short sellers had to stop shorting, because they couldn’t afford to risk the stock going up even more.

“The behavioral psychology behind this, and the game theory behind this, is exactly the same, just a different direction,” said Rishi Khanna, the CEO of StockTwits, a social-media site for investors to talk about markets. It’s like FOMO in reverse: “In a run on the bank, you don’t want to be the last one out, or you’re not going to be.” (Khanna pulled most of StockTwits’ cash out of SVB on Thursday, leaving less than $250,000 — the amount insured by the FDIC.)

The failure of SVB puts the funds of many of the tech world’s start-ups in limbo. Any amounts above the insured threshold will be meted out by regulators — or whoever takes over SVB, if a corporate buyer emerges — on an unknown timeline: worrisome news, in some cases, for companies that are trying to make payroll. (Vox Media, which owns New York, was a client.)

While bank runs aren’t new, the phenomenon of such a swift collapse predicated more on the whims of influencers — in this case, certain venture capitalists — than on financial reality seems like something that could only have happened since the COVID era, or perhaps just since FTX, when people have come to trust social media more than supposedly trustworthy institutions. Several founders I spoke with mentioned they weren’t planning to pull their money out of SVB until Founders Fund, the venture-capital outfit controlled by Peter Thiel — of Gawker-killing, Palantir-founding, and Trump-endorsing fame — advised its portfolio companies to do so Thursday afternoon. It had a galvanizing effect: Think Elon Musk tweeting “Gamestonk!!” in January 2021. Various other prominent VC firms, including Union Square Ventures and Sequoia Capital, offered version of the same guidance.

“I certainly think there’s an unbelievably irony — in effect that the bank that was serving the venture-capital industry was a target of the memeification of venture capital; the rightest, loudest voice. And that leads to this false-expert dynamic,” said Ryan Falvey, a managing partner at Restive. “And there are certainly people who started this saying, ‘See, I told you so,’ and yeah, obviously.” It was a common, if bitter, sentiment in the VC world: “Looking forward to the tweets from the VCs who sparked this bank run congratulating themselves on their prescience,” Matt Harris, a partner at Bain Capital Ventures, which invests in financial-services companies, tweeted after SVB failed.

“The loudest voices were yelling fire in a crowded movie theater & congratulate themselves on rushing everybody out,” Mark Suster, a famous entrepreneur turned venture capitalist, griped on Twitter.

Eventually, the panic reached a tipping point, and even people who’d held faith in SVB had to ask for their money back. After all, there was a lot of risk in keeping it in a bank that might fail but virtually no downside to moving it. “What I heard was universal: ‘Try to get out whatever you can,’” said Daniel Schmerin, the co-founder and president of Metaversal, a firm that invests in NFTs and Web3 technology. “When you click on that button to approve the wire, you curse under your breath because you know you are contributing to the run. It is most unfortunate.”

The original seed of doubt, though, may well have been inadvertently planted by the bank itself. A press release late Wednesday afternoon from Silicon Valley Bank announced, in a bunch of financial mumbo jumbo, a stock offering involving “1/20th interest in a share” and a sale of assets at a $1.8 billion loss. It was difficult to parse and offered no reassurances.

Still, the moves weren’t all that out of the ordinary for a bank dealing with the current tough market conditions, between rising interest rates and a larger swoon in the tech industry, which makes up the bank’s customer base. The press release also hit the internet the very same day Silvergate said it would shut down, sparking fears that SVB was part of a larger bank contagion — similar to what had occurred in the crypto industry last year. (It probably didn’t help that the two banks’ names share many of the same letters.) It didn’t matter that Silvergate specialized in crypto lending while Silicon Valley Bank catered to all sorts of tech start-ups, or that FTX’s collapse was precipitated by massive alleged fraud. It was easier to assume the worst — or, at least, to prepare for it. “Everybody is already in a mode of fear — we had everything that went down with FTX — in the start-up world,” said Khanna.

One major difference between the GameStop and SVB sagas is the winners and losers each produced. With GameStop, Redditors got rich (at least some of them did for a little while), and the collapse of the investors shorting the stock at least gave them a sense of perceived victory over an adversary. In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, the start-ups and VCs who perpetrated the collapse have lost an ally.

Erik Anderson, a former VC turned CEO, had managed to raise a fresh round of financing for his company SIQ Basketball, which makes a “smart” basketball with a corresponding app, just two weeks ago. He had deposited all the money, more than a million dollars, in Silicon Valley Bank. He tried to move the money out on Thursday, but the wire transfer still had not come through after SVB failed. “People started pulling at the thread, and everything just started unraveling,” he said, noting that the panic accelerated when major VCs started encouraging people to exit. “And that is when it’s too late.” He’s not sure now whether he’ll be able to use much of the money he raised. “We just brought in over a year and a half of runway,” he said, “And it lasted potentially two weeks.”