On Friday night, the clock ticked toward the Supreme Court’s 11:59 p.m. self-imposed deadline to rule on access to medication abortion. Deeply conservative lower-court judges had thrown down the gauntlet, drastically curtailing what’s left of abortion access and daring the Court to let them do it via its so-called shadow docket — what’s meant to be a temporary, procedural stage rather than the exhaustively briefed and argued merits docket. In his forthcoming book, The Shadow Docket, University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck describes its increasing use as the Court intervening “preemptively, if not prematurely, in some of our country’s most fraught political disputes through decisions that are unseen, unsigned, and almost always unexplained.” The shadow docket’s use spiked during the Trump administration, enabling some of its most egregious policies via a legal backdoor. Less than a year after overturning Roe v. Wade with Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, would the Court use this power to yank a pill approved 23 years ago on the shakiest of legal grounds?

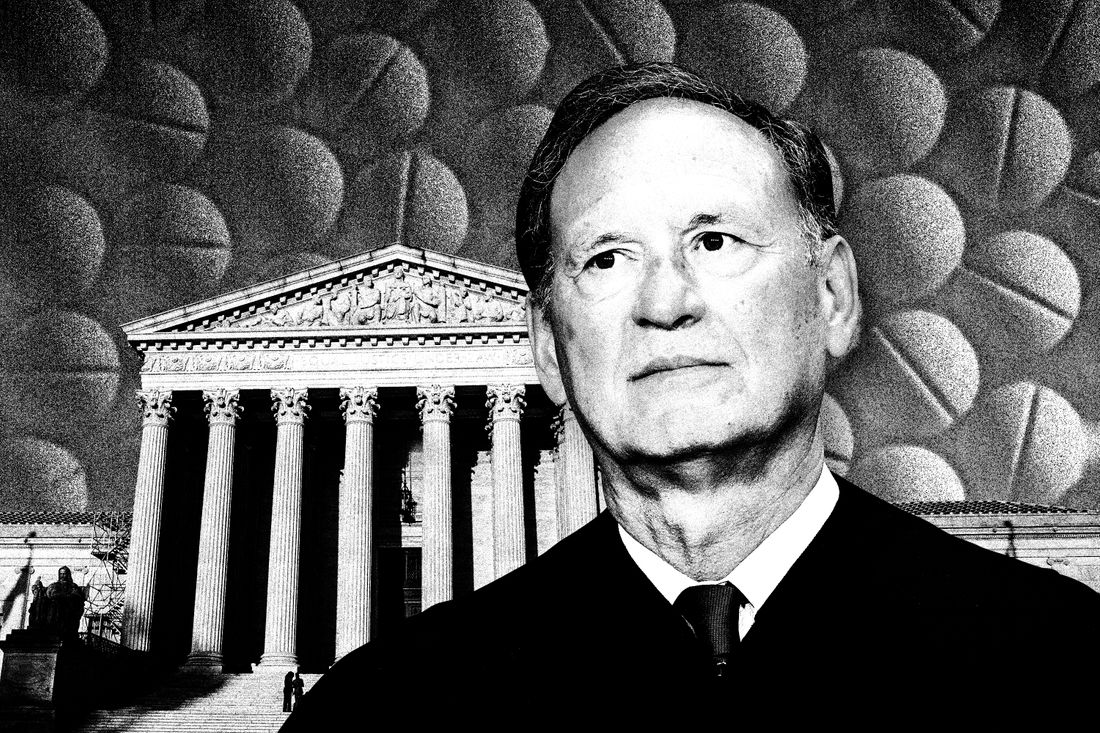

Just before 7 p.m., the answer came: no, at least not yet. Dobbs author Samuel Alito is pissed. Alito’s solo written dissent sourly took on not just the case at hand but critics of the use of the shadow docket in general — including some of his fellow justices. To break down this intriguing turn of events, I spoke to Vladeck about his critique of the shadow docket and why it has gotten under Alito’s skin.

What is the shadow docket? Why should nonlawyers care about it?

The shadow docket is an evocative shorthand that Will Baude, the Chicago law professor, coined to describe basically everything that the Supreme Court does other than the merits docket — so other than the 60 to 70 lengthy, signed decisions that we get each term in cases that were argued and that got the full nine yards of process.

Will’s insight, which I’ve somewhat shamelessly appropriated, is that there’s a lot of important stuff that actually happens in the shadows — that just because the Supreme Court doesn’t write as much, and just because it doesn’t explain itself as much, it doesn’t make a lot of these orders any less important or impactful. He wrote this in 2015, but the irony is that, if anything, the ensuing eight years have totally blown that up. We’ve been hit over the head with example after example of incredibly significant rulings that the Court has handed down through unsigned and usually unexplained orders — like the one we got Friday night.

Was there one moment for you when you thought, Something big is going on here that I need to devote my time to understanding?

Before 2017, it was exceedingly rare for the Supreme Court to use any kind of emergency order to adjust federal or even statewide policies. Almost all of the pre-2017 cases were death-penalty cases where emergency orders were simply about whether an execution would go forward. The real shift that got me working on this was starting with the second version of the travel ban, when the Court allowed the Trump administration to carry out a lot of it. Then over the ensuing summer of 2017, there was all this litigation over what the stay meant, where it’s just, and it seemed like Pandora’s box had been opened. The Supreme Court just all of a sudden seemed to be much more willing to resolve these kinds of questions through this extraordinary, abbreviated posture. The Trump administration was quite successful in court, but I think part of its success was grabbing procedural victories in cases in which it was unlikely to grab legal ones.

Obviously, in 2017, Trump comes into office and the Court starts to transform. Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh join the Court — and, eventually, Amy Coney Barrett does too. Is it fair to say that this increase you’re talking about is a joint project between the Trump administration and its appointees? One that Alito and Thomas were excited to join?

It takes two to tango. It wasn’t just that the Trump administration was so much more aggressive compared to its predecessors in trying to use unsigned, unexplained orders to carry out policies. It’s that the Court largely acquiesced. The Trump administration went to the Court 41 times in four years for emergency relief. That’s in contrast to eight requests over the prior 16 years from the Bush and Obama administrations. A really important part of the story is that the Court granted 28 of those requests in whole or in part — this is important — and never suggested that any of the requests it denied were somehow overreaching or inappropriate.

I think it was a combination of the executive branch pushing the envelope, the justices letting it push the envelope, then while this is all going on, two really important changes took place in the Court’s membership.

You observe that this pattern didn’t last under the Biden administration.

What’s remarkable is that all of the justifications that could have explained the Court’s behavior disappear as soon as there’s a Democrat in the White House. To me, that’s the problem with the shadow docket. In the absence of principled explanations, you have behavior that certainly looks like the explanation is partisan.

One of the most notorious examples of the shadow docket, in terms of real-world impact, was when the Court used SB 8 to allow Texas to ban abortion past six weeks before the Court had even overturned Roe. Why do it this the way and not wait for a decision in Dobbs on the merits docket a few months later?

I honestly don’t know. I have to say that I’m not surprised by the Court very often. I’ve become fairly cynical. SB 8 was deliberately and openly an attack on the ability of federal courts to enforce the Constitution. To this day, I remain floored that there were five justices as opposed to two or three who were willing to let that attack succeed.

In the face of a lot of public backlash, Alito gives a speech at Notre Dame inveighing against “the catchy and sinister term ‘shadow docket’” — responding to you, Adam Serwer, and others. Why do you think that the criticism of the shadow docket gets under his skin?

It’s a great question, and it means getting into Alito’s head.

Well, you could get into his jurisprudence — if there’s a really principled reason why he’s doing this.

It’s interesting. Look at his dissent on Friday. He complains about hypocrisy on the shadow docket, then says, “Because they were hypocritical, I’m going to be hypocritical too.” I think he’s trying to relitigate the backlash to SB 8. Remarkably, he cites this really cryptic concurrence that Justice Barrett wrote in October 2021. This was a challenge to the vaccination mandate for Maine health-care workers, who tried to get the Court to block the mandate, relying on the same arguments that had succeeded over and over the previous term in blocking California’s COVID-mitigation measures.

This time, Barrett and Kavanaugh vote to deny relief. You end up with Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch in dissent. Barrett writes this cryptic opinion that Kavanaugh joins, where she says, “Just because you’ve met the criteria for emergency relief doesn’t mean that we have to grant it. We should use our discretion.” She doesn’t say how that discretion is going to be informed or bound. She just says it’s discretionary.

And you saw this vote breakdown as a signal that Barrett and Kavanaugh were breaking away from Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch?

The data has, at least to some degree, born that out. We’ve seen a whole bunch of more emergency applications where Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch are dissenting since October 2021. I think part of what’s going on here is that Alito is angry. One, because he doesn’t think that the blowback to the Court’s use of the shadow docket was fair. (That’s the Notre Dame speech.) And two, because he thinks the blowback cost him two votes.

I think the question is this: What’s the lesson there? Is the lesson that public response actually had an impact? If so, I think that’s a pretty big deal. So many folks are fatalistic today about the idea that the Court is subject to any public pressure. That said, I’m not in a hurry to give the Court a participation trophy for what should have been a no-brainer. I do think that the real takeaway from Friday is not that somewhere between five and seven justices voted for one of the most obvious stays the Court’s ever going to grant. It’s that Alito felt inclined to dissent in the way that he did.

I am interested in the way the interpersonal dynamics play out here. Alito is taking a potshot at Barrett for being a hypocrite on the shadow docket, right?

Citing her opinion in the Maine health-care case is unequivocally a potshot.

Is there potentially a rift opening up here?

That or there’s a rift that’s been there for a while but this is the first meaningful public evidence of it. One of the things I didn’t appreciate about the shadow docket until I started working on the book is that there’s sometimes more honesty on the shadow docket than there is on the merits docket. The justices have less control over the cases. They have less time to think through the implications of what they’re saying.

Less time to polish and revise.

Exactly. When the justices write on the shadow docket, I actually have found the opinions to be far more revealing, instructive, informative. You see the justices saying things that perhaps you wouldn’t expect in a merits opinion. I think there’s this question: Which is the real Court? The answer is both of them. That, to me, is the takeaway here — that you can’t look at one without looking at the other. And the reality is that we still have a whole bunch of huge merit rulings coming down the pipe, and it’s very possible that they will all be best friends.

In your book, you mention that Congress could do something about the abuse of the shadow docket. It’s hard to be optimistic about that.

I think what has happened on the shadow docket in the last few years is just one symptom of a broader disease, which is just the extent to which the Court has become completely unchecked. One of my hopes in writing the book is not necessarily compelling Congress to take specific action but reminding it that, for most of the country’s history, Congress was regularly involved in conversations about the shape and size of the Court’s docket — that it regularly exerted pressure on the justices through non-substantive means. I think there are lots of respects in which having Congress do anything would be a really helpful first step back up that mountain.

I wonder if one reason some of the justices are so defensive about the shadow docket is that it underscores the general secrecy and unaccountability of the Court. The shadow docket is a symptom of the black box that is the Supreme Court. There’s so much that we don’t know. Even the limited disclosures that the justices are asked to do are incomplete — at least in the case of Clarence Thomas. Yet at the end of your book, you argue that we need the Supreme Court. These procedural abuses and your disagreement with the merits of opinions in many cases don’t lead you to say, “Let’s throw it all away.”

It’s not that I don’t understand the folks who say we should burn the thing down. I’m a progressive. I get it. But I think that it’s myopic, because if we look at what’s happening in parts of the country where majorities, or not-so-democratic majorities, are running roughshod over what really ought to be pretty basic principles of democracy, speech, and equality, it seems like we ought to aspire to a better Court and not to no Court — that no Court is not a solution that’s going to be sustainable in the long term.

I recognize that that’s going to be a bitter pill for contemporary progressives to swallow, but it’s part of why I think the conversation needs to be on terms that are more institutionalist. That instead of talking about all of the ways Dobbs and Bruen (which struck down New York State’s gun law) are wrong — and they are — we should talk about all of the ways the Supreme Court’s behavior as an institution ought to offend even the people who think they’re right.

That, to me, is the only way we’re ever going to forge any consensus about how to make the Supreme Court a healthier institution in our culture — and how to make the Supreme Court more responsible as an institution.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

More on life after roe

- ERA Ratification Is Now Up to Trump’s Supreme Court

- The Unlikely Reason RFK Jr. Could Be Rejected by the Senate

- Project 2025’s Mastermind Is Obsessed With Contraception