This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

As it took off from Dillant-Hopkins Airport in Keene, New Hampshire, on the afternoon of March 3, the Bombardier Challenger 300 business jet provided an apt illustration of why private flying is so popular among those who can afford it. Dana Hyde, a 55-year-old Beltway lawyer who had served in the Obama White House, had flown up from Virginia the day before with her husband, Jonathan Chambers, and their son Elijah to visit colleges in New England.

The three passengers were able to spread out in a cabin that accommodates up to 16. The trip, which would have taken more than eight hours by car, would be less than an hour, with no hassles at airport security, waiting in line to board, or juggling their schedules to match the airline’s — they just told the pilots when they wanted to go, where they wanted to go, hopped on, and left. After a brief delay due to an aborted takeoff attempt, the plane lifted off from Keene at 3:36 p.m., according to publicly available location data. It was a good day for flying: Winds were calm, the temperature a seasonally mild 44 degrees. Given the jet’s cruising speed, the family could expect to be on the ground at Leesburg Executive Airport by 4:30 p.m. From there, it would be a 30-minute drive to their home just across the state line in the affluent riverside village of Cabin John, Maryland.

A two-day private jet trip like this costs about $25,000 to book from a charter company, but the family had the plane at its disposal because Chambers is a partner in Conexon, the consulting company that owns the plane. A onetime Republican staffer for the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, Chambers had joined the Federal Communications Commission in 2012 and assisted in rewriting the rules for how the government helps subsidize telephone and cable services in rural communities. In 2016, he left government service and co-founded Conexon to help cable companies take advantage of the rules he had written.

Hyde had an even more impressive résumé. Born to a single teenage mother, she grew up in rural eastern Oregon, then attended UCLA and got her law degree at Georgetown. From there, her star rose quickly. She worked as a White House special assistant during the Clinton administration, then served on the 9/11 Commission. After a spell at the State Department, she was picked by the Obama administration to head the Millennium Challenge Corporation, an independent agency set up during the Bush years to fight global poverty by funding projects in countries that follow free-market economic policies. Having come from modest means herself, “working to fight global poverty” was important to her, Hyde said at her Senate confirmation hearing, but so was efficiency. “I believe in data-driven, cost-effective policies. I want the American people to always get their money’s worth from anything their government does on their behalf,” she testified. Confirmed unanimously, she steered the agency and its billion-dollar budget from 2013 until 2017. She thereafter worked as a partner at a Jerusalem-based venture-capital firm and was co-chair of the Aspen Partnership for an Inclusive Economy.

A gentle breeze was blowing from the south as the plane rose from the 6,000-foot runway. It banked to the left as it climbed over the foothills of the White Mountains, then leveled its wings to follow the course of the Connecticut River southward. What happened next can be pieced together from a report released a month later by the National Transportation Safety Board.

At 3:44 p.m., the plane was eight minutes into its flight and 23,000 feet over Amherst, Massachusetts, when, without warning, it pulled up so violently that those sitting were pressed down into their seats with a force of four times their weight. Then the plane porpoised downward with nearly as much force. Anyone not belted into their seat would have been flung onto the ceiling. Cups, plates, briefcases, and even the hair on heads rose as if summoned by static electricity; then all, people and debris alike, slammed onto the floor as the plane arced skyward again. By the time the pilots regained control, it looked as though a hurricane had passed through the cabin.

Chambers told the flight crew his wife was injured. The co-pilot went back to check on Hyde and provided what first aid he could, then returned and reported that her condition was serious. They had to divert.

“We need to descend,” one of the pilots radioed to air-traffic control, his voice audibly tense. “We need to descend. We need to go to an airport.”

“Okay. You know where you need to go?”

“We need to go to an airport that has medical facilities nearby.”

The air-traffic controller offered a number of options, and the pilot chose Bradley International Airport, which at that point lay 20 miles directly ahead. As the plane began its descent, the air-traffic controller asked, “What’s the nature of the emergency?”

“Uh, passenger is, has a concu — uh, a laceration.”

“Laceration, roger, we’ll make sure there’s medical there for you.”

The plane landed at 4 p.m. and taxied to the private aviation ramp where an ambulance was waiting. Hyde was rushed to the Saint Francis Medical Center in Hartford, where she died of her injuries later that evening. Connecticut’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner reported that the immediate cause of death was blunt force trauma to the head, neck, torso, and extremities.

Hyde’s death made headlines. “Former White House official dies of injuries after jet turbulence,” declared the Washington Post. It wasn’t just that such a high-ranking official had died but that she had seemed to succumb to a phenomenon that everyone who flies hates but few think of as life threatening.

To be sure, dangerous turbulence is far from rare. Just two days before, a Lufthansa flight en route from Texas to Germany encountered severe clear-air turbulence while flying over Virginia and had to divert to Washington, D.C. Passengers reported that the plane seemed to be in free fall for five seconds and that plates, glasses, and food from the dinner flew up to the ceiling and then crashed down throughout the cabin. Seven people were later hospitalized. As scary as such episodes are for passengers, they rarely result in death. In fact, while 146 passengers and crew were injured by turbulence in the United States between 2009 and 2021, none of them died.

The unusual nature of Hyde’s death, together with her connections to the Clintons, set conspiracy theorists’ imaginations spinning. “The Clintons strike again,” wrote one commenter on Facebook. Wrote another, “Next you will mysteriously see this crew die over the years from ‘accidents.’” There were some reasons to wonder about the accuracy of the media’s coverage. Apart from the rarity of turbulence fatalities, there was the fact that weather conditions at the time of the incident had been calm and not conducive to turbulence. Indeed, no other aircraft operating in the area had reported it.

As they began to look into it, investigators from the NTSB quickly realized that turbulence most likely hadn’t played a role at all. Instead, the likely causes seemed partly mechanical and partly human in nature.

An early sign of trouble had occurred during the takeoff roll. As the plane accelerated down the runway, one of the pilots noticed that an airspeed indicator wasn’t working. Concerned, they braked to abort the takeoff and taxied back to the ramp, where they discovered they had failed to remove the cover from one of the airspeed probes. Generally brightly colored so they can be more easily seen, these covers are put over the probes to keep out dirt and insects between flights; removing them is part of the preflight ritual, so one being inadvertently left in place suggested the inspection of the aircraft had not been done with much care. The pilots decided to press on anyway.

As the plane started its second takeoff roll, they noticed yet another problem: They had forgotten to enter into the plane’s computer the correct speed at which the pilot at the controls should pull back to initiate the takeoff climb. Rather than abort the takeoff a second time, they continued since the co-pilot knew the correct speed from memory. Again, the thing itself wasn’t such a big deal, but it seems indicative of a sloppy mind-set. “There just seemed to be a lot of misses,” says aviation consultant Brian Foley.

Just two minutes into the flight, as the plane was completing its initial climbing turn to the south, warning messages began sprouting on the display panel: “AP STAB TRIM FAIL,” “MACH TRIM FAIL,” “AP HOLDING NOSE DOWN.” They popped up so quickly that, looking back on it later during interviews with the NTSB, neither pilot could remember what order they had appeared in or whether other messages had come up as well.

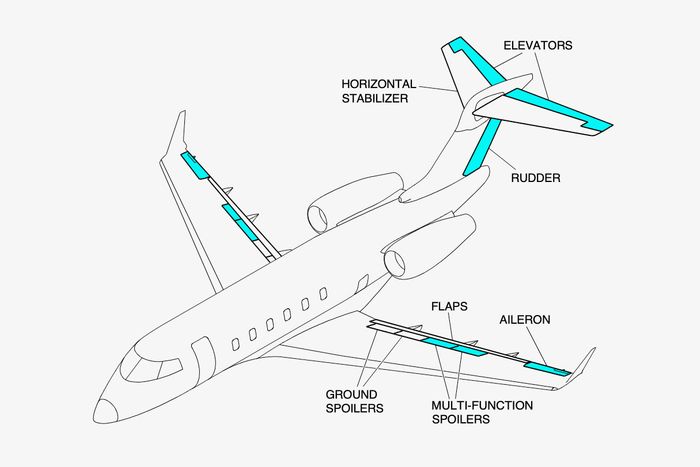

These messages relate to systems that control the pitch of the aircraft — that is, whether the nose points up or down. The horizontal stabilizer (STAB) consists of two small wings at the top of the tail, like the top of a capital T, that keep the pitch steady. To move the nose up or down, the pilot (if flying manually) or autopilot moves a hinged slat on the back of the stabilizer, called an elevator. Moving it can require a lot of force, so once the plane’s nose is in the desired position, the stabilizer can be rotated to neutralize this force, a process called “trimming” (TRIM). The “AP STAB TRIM FAIL” alert meant that, due to some unknown failure, the autopilot couldn’t trim the stabilizer so was having to exert continuous force to hold the pitch steady. Specifically, it was having to push the nose down, as indicated by the “AP HOLDING NOSE DOWN” alert.

When emergencies occur in flight, pilots are trained to immediately refer to the appropriate checklist that will tell them what to do step-by-step. So the co-pilot took his iPad and opened the Primary Stabilizer Trim Failure checklist. He showed it to the captain, who agreed it was the right one to run. The first item on the checklist was to shut off the stabilizer trim switch. The co-pilot did so and all hell broke loose. The plane jerked up so violently that the captain, who was flying the plane with one hand, had to grab the controls with both.

Apparently, when the autopilot was turned off, it suddenly stopped holding the nose down against the force of the out-of-trim horizontal stabilizer. The effect was like a tug-of-war team that lets go of its rope: With no opposing force, the other team jerks in the other direction. As the plane bucked up, the captain aggressively pushed down on the controls, forcing the plane back toward the horizon. But he overcompensated and swung into a dive, then into a climb again. The captain told the co-pilot to put the stabilizer trim switch back in its original position. He did, and they were able to regain control of the plane. But for Hyde, it was already too late.

The funeral was held five days later at Temple Micah, a D.C. synagogue where Hyde and her family worshipped. Hundreds of people attended, including a former Treasury secretary and a national security adviser. Afterward, her remains were flown to Israel for burial. Chambers issued a written statement eulogizing his wife, but the family has otherwise been private in the aftermath. (Conexon declined to comment for this story, and said in a statement it is “deeply saddened by this tragic event. We extend our sincerest sympathies to all those affected by this accident.”)

The NTSB is continuing its investigation. It usually takes about a year for the board to issue a final report detailing its full findings. While much about the case will remain mysterious until then, it’s likely the accident will be found to involve a dynamic that has made up an increasing share of aircraft accidents in recent years: the unpredictable interplay between flawed automation and the vagaries of human behavior. The most famous cases are the two fatal 737 MAX crashes that together killed 346 people in 2018 and 2019. In each accident, surprised pilots struggled to deal with autopilots whose behavior they didn’t expect and didn’t know how to restrain.

A lesser-known incident that more closely parallels the accident that killed Hyde took place in 1999. A Falcon 900B carrying ten passengers from Athens to Bucharest was descending toward its destination when one of the pilots inadvertently disengaged the autopilot. That plane too had been badly out of trim, and as soon as the autopilot switched off, the plane’s nose swung violently upward. One pilot pushed the nose back down but overcompensated, leading to a sequence of violent oscillations. The aircraft’s porpoising was so violent that seven of the ten passengers were killed. The accident report noted that “the cabin was destroyed … most of the armrests were torn off or broken.” The aircraft’s roof was punctured by the corner of a metal catering locker.

The plane that killed Hyde had well-known issues involving the stabilizer trim system. Just nine months before, the Federal Aviation Administration had issued a directive regarding Bombardier Challenger jets owing to “multiple in-service events” in which the plane had engaged in unexpected behavior after “STAB TRIM FAULT” messages appeared on the flight display. The directive called for operators to revise the procedures for pilots to follow, including “expanded preflight check of the pitch trim,” and warned that “uncommanded horizontal stabilizer motion could result … in loss of control of the airplane.”

David Sullivan-Nightengale, a systems-safety engineer who has worked at Honeywell and Lockheed, says the best way to avoid aviation accidents like these is to work out flaws at the design level. The problem is that overhauling a system’s design may make changes so expensive as to become uneconomical. So companies attempt to calculate the probability that a design flaw will cause something to go wrong in the future — and how dangerous or damaging the result will be.

“Unfortunately, they don’t consider the probability correctly sometimes,” Sullivan-Nightengale says, “and the occurrences are much higher than expected.” If a manufacturer chooses not to fix an underlying safety issue, a less expensive way to mitigate any ensuing risk is to adapt training protocols so that pilots know what to do if things go haywire. Unfortunately, that doesn’t always work out. “The least effective means of dealing with a hazard is training the pilots to mitigate it,” he says.

The danger is especially acute when pilots are relatively inexperienced. Neither of those in the Hyde case had more than 100 hours in the Challenger 300. That may be one reason why the checklist they ran after getting the “AP STAB TRIM FAIL” warning turned out to be the incorrect one. On the right checklist, the first item is to turn on the “fasten seat belt” sign. If they had, and Hyde had complied, she likely would still be alive today.

Until the NTSB completes its investigation, we won’t know for sure what led to Hyde’s death. But even if poorly designed automation and inadequate pilot training are found to have been at play, that doesn’t mean the finding will lead to any major changes. Aviation regulators accept different degrees of risk depending on the kind of flying that’s going on. The strictest rules apply to commercial airlines, where hundreds of lives may be at risk on every flight. For recreational aircraft that carry only one or two people, the regulations are quite relaxed. Private jets fall somewhere in between.

This shading of risk is why you’re far more likely to die on a millionaire’s jet or helicopter than in a seat in economy class. In the past 14 years, not a single passenger has died in a U.S. airline crash, but dozens die every year on chartered and private aircraft. Among the recent notable victims were Alaska senator Ted Stevens, billionaire Chris Cline, French businessman and politician Olivier Dassault, and basketball great Kobe Bryant.

If a private aircraft goes haywire once in a while and slams some of its passengers to death, that’s an outcome no one is happy about. But it’s not necessarily, from a regulatory perspective, an unacceptable risk.